A Brief Drive in Saudi Arabia Changed My Life

What’s it like to be arrested for ‘driving while female’? As the kingdom prepares to lift its ban, an activist tells her story.

I never set out to be an activist. I was a religious girl, born and raised in Mecca. I started covering myself with abayas and niqabs before it was even required, simply because I wanted to emulate and please my religious teachers. And I believed in a highly fundamentalist version of Islam. For years, I melted my brother’s pop music cassette tapes in the oven because in fundamentalist Islam such music is considered haram, forbidden.

The only somewhat rebellious thing I did at a young age was to get a job as an information security specialist. I got married at age 24, had a son, and then got divorced. But once I turned 30, I started to do daring things on my birthdays. On my 30th birthday, I went skydiving in the U.S. The next year, I bought a ticket to Puerto Rico and spent time traveling alone. And back in Saudi Arabia in 2011, when I turned 32, I decided that I would start driving.

I went to meet my brother at his house. He handed me the keys to his car, a Hyundai Azera sedan, and told me, “I will be with you until the end.” He, my sister-in-law, their baby, and my five-year-old son Aboudi got in the car. I got in as well, but unlike every other time that we had ridden together like this, I was behind the wheel. I was excited but terrified. I hoped having my family with me would offer some protection if I was harassed. As I drove, I asked my sister-in-law to take out her cell phone and make a video. I was already thinking about how I could post it on YouTube.

I’d learned the proper rules of driving when I was living in the U.S.—I got a New Hampshire and then a Massachusetts driver’s license. But in Saudi Arabia, I never got behind the wheel. Saudi women rely on drivers to ferry them from place to place. We are at their mercy. Almost every woman I know has been harassed by a driver. They make comments about our appearance; they demand more money; they touch us inappropriately. Some women have been attacked. I’ve had drivers make all sorts of inappropriate comments and tape my calls when I’ve used my cell phone, thinking maybe they could blackmail or extort me.

I drove for about 30 minutes until we reached Corniche Street. Right away, I saw the first traffic cop. I held my breath as we passed. But he did not wave me over. Nothing happened. “We have the green light!” I shouted. “We have the green light! It’s okay!”

I kept on driving, watching the faces of the other drivers on the opposite side of the road. All of them stared, even swiveling their necks around as we passed. Some glanced down or looked away and then looked back, as if they could not believe what they were seeing: a woman driving. I looked them straight in the eye and smiled, as if to say, Yes, you are seeing a woman behind the wheel. Time finally to get used to it.

I continued until I reached an intersection. There, directly facing me, was another traffic cop. I came to the horrible realization that perhaps the first traffic cop had not reacted simply because he had not seen me. As the second traffic cop looked at my vehicle, our eyes locked. When the light changed, I made a left turn, directly in front of him. I was barely through the lanes for oncoming traffic when I heard the command blaring over the police address system: “The Azera, pull over.”

I jerked the car to a stop. I blew out a big breath as I saw him striding up to my window. Then I saw that he was smiling, amused. “Are you from Saudi?” he asked. “Do you know, in Saudi, women don’t drive?”

I smiled back and asked him his name. Then, caught up in the moment, I made a huge mistake. I told him my name. I handed over my brother’s Saudi license, my Massachusetts license, and the car’s registration. And then I added, “Sir, there is nothing in the traffic police code that says I cannot drive.”

The traffic cop inspected the documents, all of which were valid. With a surprised look and a big smile, he told us to wait and then called for backup. While we were waiting for the second officer, a black car stopped in the middle of the road and the man inside looked over at me, still sitting in the driver’s seat. “Who is this woman?” the man demanded. The traffic cop answered, “Manal al-Sharif.”

The man in the black car made a call that would change my life. Within 10 minutes, a huge vehicle raced up, its tires squealing as the driver hastily applied the brakes. I was now surrounded by vehicles on all sides, but this last one was the most terrifying. Painted on its side was the insignia of the Mutawa—the Saudi religious police, which is like an unmarked army, invisible and yet everywhere all the time. Two men quickly emerged, one very heavy, the other thin. They were from the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice.

My brother immediately hopped out of the car and went to talk to them. They were yelling that they would not permit such an “outrageous mixing of the sexes” as had apparently happened when I, a woman, sat in the driver’s seat next to a man. “But I’m that man and she’s my sister!” argued my brother.

Eventually, the Mutawa grew tired of harassing him and approached me in the car. I triple-checked that the doors were locked. The heavy-set Mutawa tapped on the car window and called me “bint,” a pejorative term for “girl.”

I cracked the window and called out to them, “First of all, pay your respects. You may call me Umm Abdalla”—meaning Abdalla’s mother, the appropriate form of address for a mother in Saudi society. “Secondly,” I said, “this is a traffic issue, not a moral issue. I was driving with a valid license, there’s nothing immoral about that. This is an issue for the traffic police, so I’m not going with you.” I closed the window.

The men from the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice were enraged. The heavy-set one pounded on the passenger side window, inches from my face. Like a furious, thwarted cartoon character, he pulled repeatedly on the handle of the locked door. Then he banged on the door. Spit flew from his mouth and collected on the glass as he bellowed at me over and over, “Get in our car! Come with us!” I said through the glass, “Over my dead body.”

For nearly an hour, the Mutawa tried to intimidate us. Finally, as dusk approached, my brother and I agreed to sit together in the backseat of his car and allow the two Mutawa to drive us to the traffic station. My brother quickly hailed a taxi and placed his wife, their son, and Aboudi inside. It all happened so fast, I didn’t even get a chance to say goodbye.

I sat up as straight as I could and spoke directly to the Mutawa. “You know this is illegal. You know you have no right to drive our car,” I told them as we drove to the station. “After this, I can file a complaint against you. And I will.”

It was sundown when we reached the gates of the Thuqbah traffic station, which meant that it was prayer time. Within the compound, there was only a place for men to pray; no women were allowed. I saw a small window of opportunity.

“Can I sit in the car and wait?” I asked. “Yes,” they said. Once the men had walked off, I powered on my phone. Holding my breath, hoping the battery would last, I dialed one number. As quickly as I could, I explained where I was. “Please,” I said, “get the word out.”

On the other end of the line was a newspaper reporter from Al Riyadh. At least now I believed that I would not disappear without a trace. When the Mutawa, the traffic police officers, and my brother returned, we went inside the station. I was surprised to find the traffic police colonel waiting for us. He looked at the Mutawa and asked, “What’s going on?”

The men told him to ask my legal guardian. This is the standard treatment for Saudi women. We are expected to sit in silence while our male keepers speak for us, act for us, and ultimately decide for us. But I had not come this far to stay silent.

“He’s my little brother,” I said. “I should be his guardian.” The Mutawa were shocked. I’m sure they wanted to slap me. I explained to the colonel what had happened, and asked why, when this was a traffic disagreement, the Mutawa were involved. “Do you know that what you did is illegal?” the colonel asked. “Sir,” I replied, “I did not violate any traffic code. According to Section 32 of the Traffic Statute, there is no gender specification in the driver’s license application. In fact, there is nothing in the statute anywhere that says women can’t drive.”

He leaned back in his chair. “You can cite the statute?” “Yes. I’ve been studying the code for days, sir.” He sat still for a moment, silently assessing me. Finally he said, “Well, you need a Saudi license to drive here.” “Sir, true, but,” I said, without blinking, “I am allowed to use my valid foreign driver’s license for up to three months until I get a Saudi one.” I reached into my bag and handed him my completed driver’s license application. I could nearly hear the colonel think, Oh my God, who the hell is this woman?

Waving his hand as if he were shooing off flies, the colonel said, “Put your papers away.” Then, turning to question my brother, he asked, “Did you give her the keys?”

“Yes, I did,” my brother answered calmly. “I am fine with her driving.”

My bag was confiscated. We were taken to another room, and this one had a landline. I wanted to use it to check on my precious Aboudi. It was nearly bedtime. I wanted him to hear his mother’s voice wish him sweet dreams, so he might sleep soundly after everything that had happened. But when I asked to use it, the phone was ripped from the wall and taken away.

My brother and I performed our evening prayers as officials from different authorities began arriving at the station. We could hear their voices and the clipped sounds of their shoes as they moved across the hard, slick floor.

“Manal, they’re planning something,” my brother said in a low voice. He motioned with his eyes toward a few men who wore no uniforms. They were standing slightly apart and spoke only among themselves, monitoring everything else.

“Are those the Dababees?” I asked him under my breath.

“Yes,” he said grimly. It’s a nickname Saudis use for the Mabahith, the “domestic intelligence agency,” or secret police. Dababee literally means pushpin or tack—something with a sharp point that can stab you in an instant.

Panic was beginning to creep into my voice. “Why, why, why, why are they here?”

“I don’t know,” he answered. “Let’s not even talk about it.”

After some time, the colonel reappeared and introduced me to the chief of the Khobar Police. “Aren’t you Manal of June 17?” he asked.

So the head of the police knew about Women2Drive, a campaign I’d been organizing to urge Saudi women to drive through the streets in June. “Yes,” I answered.

“Why didn’t you wait until then? Why did you drive now?”

“There is no traffic code banning women from driving,” I said again. He didn’t reply, so I asked, “May I go now?” He said, “We can’t release you until we get approval from the governor.”

Around 10 p.m., the provincial governor’s office finally sent over a pledge for me to sign: I, Manal al-Sharif, will never drive on Saudi land ever again and I will stop the event on June 17.

The police chief asked that the part about June 17 be removed, and the governor’s office reissued the pledge. Now it simply said: I, Manal al-Sharif, will never drive on Saudi land ever again.

I looked at the pledge. I hadn’t eaten. I hadn’t slept. My throat was hoarse. I wanted to see my son. It would have been so easy to sign it and leave. “I don’t accept this,” I said. “I broke no code.”

“You … you have to sign it,” the police chief gently urged. “If I don’t?” “Then I fear we will have to hold you in detention until you do.” “Sir, I broke no statute. Tell me now what code I broke, and I will sign. What code did I break?” After a minute he said softly, “You broke orf.” In Saudi society, orf means tradition or custom, a practice or convention. It is not the official code.

I turned to the chief and said very deliberately, “I want to hear both of you say it. Please repeat it.” The chief stated, “You broke orf.” “Say it again.” “Orf. You broke orf.” “Good, we agree. I broke no traffic code.” It was a small victory, but I wanted to prove to at least the men in the room that I had broken no Saudi statute by driving.

“Still, you have to sign the pledge. Or else, sadly, we must put you in detention,” the chief said. I signed the pledge. I said to myself as I wrote my name, “I’m going to use the fact that I broke orf and no code to keep going.”

It was after 11 p.m. when we were released from the station.

I thought that I would come home to a silent house, but instead there was a small crowd waiting. After my one furtive phone call, not only had the local papers reported on what had happened, but Ali Alalyani, the host of the Ya Hala show, had broadcast news of my detention to the entire nation. My sister-in-law had contacted Ahmed, who managed the Women2Drive Twitter account. He tweeted out what had happened, thousands more retweeted it, and international press outlets picked up the story. Someone else had put up a “Free Manal” Facebook page, and within a couple of hours it had more than 5,000 likes.

My friends were giddy. “The entire world is talking about you!” they exclaimed. “They’re calling you the Saudi Rosa Parks!”

My eyes were watering with emotion, but I couldn’t help laughing. “You are all so silly to worry about me!” I said. I explained that the police chief had crossed out the line about canceling the June 17 event. I thought that was significant. We had tacitly been given the okay to drive that day. “We won!” I said. “I told you! My dears, you are scared over nothing! We won!”

After such an exhausting day, I wanted to pass at least a few easy hours before dawn broke and a new day began. That, however, was not to be.

The secret police came for me at two in the morning. Their knocks on the door were loud, hard, the kind that radiate out and shake the doorframe. My five-year-old son was asleep, but I was awake still, wearing sweatpants and a Mickey Mouse T-shirt. Startled, my brother jumped up and rushed to the entry. I stayed slightly behind, feeling the night air rush in as he pulled open the door. In the shadowy darkness, all we could see were men, crowding around my front stoop, pressing forward. When my brother asked them who they were, there was silence. Finally, one of them spoke. “Is this Manal al-Sharif’s house?”

My brother didn’t hesitate. “Yes.”

“She needs to come with us right now. They want to see her at the Dhahran police station.”

As soon as I heard those words, I was terrified. My brother slammed the door shut and locked the bolt. There was a pause. Then the knocking started again.

I decided to pray. In the hallway leading to my small bedroom, I performed two raka’as (the full cycle of an Islamic prayer, spoken while standing, sitting, and prostrating) and asked for God to show me the way. It was now nearly four in the morning. I felt something inside me say, “Go, Manal. You’ll be okay.”

My brother insisted on accompanying me, although all the men outside wanted me to go alone, without him, which should have convinced me that something was wrong. In Saudi society, a woman needs her official guardian (usually her father or husband) or a mahram—a close male family relative whom she cannot marry, such as a father, brother, uncle, or even a son—to accompany her on any official business.

I went back inside and put on my abaya as well as a hijab. I walked out holding my brother’s arm. I hadn’t even looked at my sleeping little boy or kissed him goodbye. I wanted to believe that I’d be back in time to wake him, feed him breakfast, get him to school, and then head to work. At most, I told myself, I would only be gone a couple of hours. At this time of night, it was less than ten minutes from the Aramco compound to the Dhahran police station.

I got into the back of one of the cars. My brother sat in the front. No one spoke. I looked out the window at the blackness, felt the car hum along the road. Five minutes passed, then 10. I could make out none of the familiar landmarks in Dhahran. We were not heading into the city.

A few hours later, I was locked inside Dammam Women’s Prison. I spent several days there while others petitioned for my release. During Friday prayers at mosques across the country, the imams stood up and applauded my arrest. In fiery sermons, they denounced me as a bad influence on other women. They condemned me for “corrupting the society” and they accused me of blasphemy and seeking to destroy Islam. I was referred to as a “whore” and a “prostitute.” According to the imams, prison was the only appropriate place for Manal al-Sharif.

I was living in Australia by the time September 27, 2017 rolled around. I woke up at 5 a.m. to give my son his medicine after a recent ear surgery. As I quickly double-checked the time on my mobile phone, a BBC breaking-news alert flashed across the glowing screen: Saudi Arabia to lift driving ban on women.

I thought my sleepy eyes must have made a mistake. I refreshed my phone and read it again. And then I read it one more time just to be sure, after which I broke into tears of joy. Within a minute, my phone went crazy, and my email was swamped with interview requests from all over the world.

This weekend, the driving ban is finally lifting. To reach this historic moment, it took nearly three decades from the first attempt to protest the ban: In 1990, 47 women staged a protest drive, after which the religious establishment destroyed their lives and reputations. We all must pay our respects to the women and men who have waged this struggle. Women campaigning to end this ban have lost their freedom, their jobs, have jeopardized their safety, and had their cars confiscated and held. They have been harassed and jailed, and their families have been targeted. They have been called every degrading name and been viciously attacked. They lost their lives as they knew them for daring to drive on the streets of Saudi Arabia.

But no more. Things started to change in 2011, with the start of the #Women2Drive movement. The struggle continued with additional campaigns, including the 2013 campaign led by the Saudi blogger Eman al-Nafjan. In 2014, another activist, Loujain al-Hathloul, attempted to cross the Saudi border from the United Arab Emirates by driving her car. She was joined by Saudi journalist Maysa al-Amoudi. Both were arrested and sent to jail for 72 days. Just last month, al-Nafjan and al-Hathloul were arrested, along with several other women’s rights activists.

I hope a woman will never again be jailed for the simple act of driving a car. Women’s rights activists must continue to observe how the law is implemented and continue to campaign to abolish the male guardianship law, which forbids women to travel, marry, or even leave prison without the permission of a male relative. We must ask for nothing short of full equality for women. Driving is only the start to ending other unjust laws, which treat Saudi women as minors, not trusted to direct their own destiny.

But this time, I do believe Saudi is changing. The current leader of the power game is Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, best known by his initials, MBS. In the spring of 2017, I had the chance to meet with members of his signature 2030 Vision team, which is in charge of the kingdom’s modernization. I was very skeptical, but after a few hours of heated discussions and many more hours of studying and reading, I became a supporter and a believer that this young man can finally bring change. When he was named crown prince, I tweeted: “Now my hopes for a better Saudi are bigger than the sky.”

MBS has reined in the religious police, which choked us, literally and figuratively, and has lifted a long list of restrictions on music, art, and cinemas, as well as on women working and attending public sporting events, and even the practice of closing shops five times a day for prayer. It’s also the first time that someone in a major leadership position is younger than me and is part of the age group that makes up the majority of Saudi Arabia’s population.

But these changes may not be permanent. The Saudi Arabian political system is very complicated. To most of the outside world, it might seem as if being a king in an absolute monarchy gives the ruler the absolute power to make any decision and execute it. In fact, the Saudi political system is riddled with many small powerful groups, each with conflicting interests. Nothing is absolute.

I do believe that allowing women to drive will be a permanent change. Few things have brought more shame to Saudi Arabia than this draconian ban. And there is more: Saudi Arabia cannot succeed economically if women who are highly educated are kept in the backseat. My hope is that economic reforms will be combined with political reforms, leading to a constitutional monarchy where people have representatives and, one day, full freedom of expression.

There can be no modern Saudi kingdom as long as women are still ruled by men. It may take a long time, but I do believe that kingdom will come.

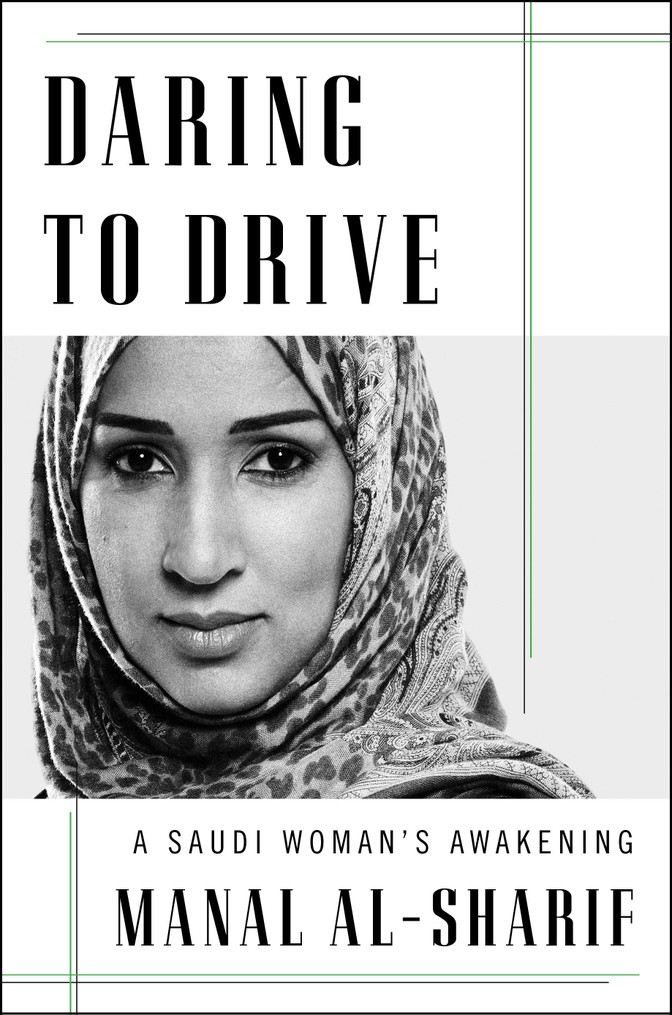

This article has been adapted from Manal al-Sharif’s book, Daring to Drive: A Saudi Woman’s Awakening.