Roberts Thwarted Trump, but the Census Ruling Has a Second Purpose

The Supreme Court rejected Trump’s citizenship question, but the ruling serves a conservative counterrevolution against the administrative state.

When the Supreme Court blocked the Trump administration from adding a citizenship question to the 2020 census, almost everyone focused on the political consequences. If the question led to an undercount of minorities and immigrants, it could affect the decennial allotment of congressional seats and electoral votes. Yet the long-term significance of the case, Department of Commerce v. New York, lies elsewhere, in what it portends across the expanse of the federal government. Like surface tremors that hint at deeper movements farther below, the census case—especially when viewed alongside lower-profile cases that the high court decided this term—signals the beginnings of a long-term shift in the tectonic plates of our constitutional system that will challenge government by administrative agency, rather than by our elected representatives.

The census issue remains in litigation, even as the administration struggles to designate which lawyers will represent it. But sometimes losing a political battle can result in winning a constitutional war. President Donald Trump might not get his census question, but conservatives who have long campaigned against the American administrative and regulatory state may receive a far greater consolation prize: The court has fired the first serious shots in decades against an administrative state run amok. The counterrevolution is on.

In the census case, Chief Justice John Roberts’s majority opinion blocked the Trump administration from asking respondents in next year’s census about their citizenship. However great its impact, the case itself turned on a technical point of administrative law. But in Supreme Court jurisprudence, even technicalities cast long shadows.

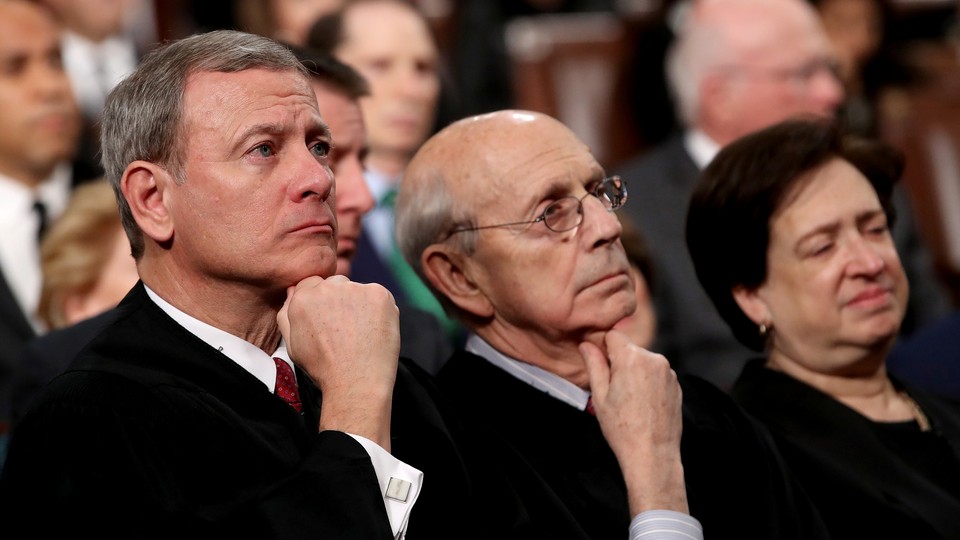

The court found that the Department of Commerce had manufactured a pretext in court for including the citizenship question. Commerce’s real reason could have been to benefit Republican states in the 2020 census by undercounting immigrants, who group more highly in blue states such as New York and California—and in the parts of red states that send Democrats to Congress. Chief Justice Roberts, joined by the four liberal justices (Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor), declared that “the evidence tells a story that does not match the explanation the Secretary gave for his decision.” The “sole stated reason” for adding the citizenship question to the census, he observed, “seems to have been contrived.” Federal agencies must “offer genuine justifications for important decisions, reasons that can be scrutinized by courts and the interested public.” Otherwise, judicial review becomes “an empty ritual.”

In dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, correctly called the opinion “an unprecedented departure from our deferential review of discretionary agency decisions.” (Samuel Alito filed a separate dissent.) Courts generally examine only the government’s stated rationale for regulation, and do not search for any hidden “real” reason that might involve politics. Subjecting agencies to more searching scrutiny in the future, rather than accepting their purported reasons, will impede the flexing of bureaucratic muscle and allow judicial second-guessing of policies. Thomas observed that “if taken seriously as a rule of decision, this holding would transform administrative law.”

In their quest to hand the Trump administration a political defeat on the census, the four liberals justices unwittingly agreed to lay the groundwork for a new world in which agencies’ explanations receive strict judicial oversight. This change alone would be significant. But couple it with two more June decisions, and this year heralds a renewed conservative judicial attack on the foundations of the administrative state. While these other decisions may not appear monumental, it is their reasoning, rather than their results, that matter.

Take Gundy v. United States, which involved a law that authorizes the attorney general to determine whether certain sex offenders have to register publicly. While unimportant on its facts, Gundy put in doubt similar grants of lawmaking that empower the federal bureaucracy to define, for instance, how clean the air should be or how far cars should go on a gallon of gas. A “nondelegation doctrine” that prohibits the excessive transfer of legislative power to executive agencies has lain dormant since 1937, when Franklin D. Roosevelt threatened to pack the Supreme Court in order to bully it into upholding the New Deal.

For conservatives committed to the original understanding of the Constitution, such broad transfers of legislative authority violate the separation of powers. The Framers granted executive power solely to the president, legislative power solely to Congress, and judicial power solely to the courts, rather than allowing their combined exercise, as in parliamentary systems. They worried that, as James Madison wrote in “Federalist No. 47,” the “accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, … may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.”

But beginning with Woodrow Wilson, progressive thinkers viewed the separation of powers as obsolete and ineffective for a modern industrial society. They urged instead that Congress delegate its powers to expert agencies, which could issue regulations without having to survive both houses of Congress and the president. The agencies would become perpetual-motion machines of progressive lawmaking.

The New Deal and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society put these theories into practice. Despite the separation of powers, federal-government agencies now exercise all three types of power—making laws, enforcing laws, and adjudicating disputes over these laws. It is the agencies, not Congress, that issue the real federal laws that most Americans encounter every day. The broad empowerment of the administrative state has created a bureaucracy with a mind of its own and has allowed our elected representatives to escape responsibility for difficult decisions. While this problem is worse with the so-called independent agencies, such as the Federal Reserve, the Federal Communications Commission, and the Securities and Exchange Commission, whose leaders cannot be removed by the president, both they and the regular executive agencies supervised by Cabinet secretaries exercise broad legislative powers without serious review by the courts.

In Gundy, a 5–3 court found no violation of the nondelegation doctrine. But beneath the surface, a conservative majority declared its intent to restore limits on Congress’s ability to give away its own power. Roberts, Thomas, and Gorsuch voted to strike down the sex-offender law outright. Kavanaugh recused himself, but his record as a lower-court judge displays a strong hostility to independent agencies. Tellingly, Alito, who concurred with the four liberals and provided a fifth vote to uphold the law, nevertheless appended a one-page statement: “If a majority of this Court were willing to reconsider the approach we have taken [to nondelegation] for the past 84 years, I would support that effort.” That makes five votes to begin restoring the Constitution’s separation of powers and prevent Congress from handing off hard decisions—and the authority to make them—to the agencies.

Another sign of the counterrevolution against administrative governance arose in Kisor v. Wilkie. That case challenged the judicial practice—known as the Auer doctrine—of accepting an agency’s interpretation of its own regulations. The Supreme Court’s 1997 ruling in Auer added to the unfair advantage enjoyed by agencies, which can already transform vague statutory commands into their preferred policies. Yet courts, which bear the constitutional responsibility to say what the law is, and which refuse to defer to the views of Congress or the president in that regard, have been lying down and playing dead before agencies.

In Kisor, a bare majority upheld Auer. But the four liberal justices had to so narrow the doctrine to attract Roberts’s unexpected fifth vote that it will now apply to few real-world cases. More important, the case planted the seeds for greater change. The four conservative dissenters not only rejected the Auer doctrine, but called for the reversal of the similar, but significantly more important, Chevron doctrine. The 1984 Chevron ruling requires courts to accept agencies’ reasonable interpretations of ambiguous statutes, which effectively allows agencies to seize sweeping powers. Despite voting to uphold Auer, Roberts declared that he would leave the door open to overrule Chevron. That’s five potential votes to kill Chevron and require judges—not bureaucrats—to interpret the law.

Put these three decisions together—the census case, Gundy, and Kisor—and we may soon have a world where Congress can no longer outsource lawmaking to agencies, courts will no longer defer to agencies’ interpretations of congressional statutes, and courts will closely scrutinize when agencies do act. The upshot of this trifecta is that power will be exercised by elected government officials or courts, not the bureaucracy. Of course, it is ironic that the census case helps facilitate this power shift, because the agency lost in court for doing what the president wanted. But legal principles far outstrip the narrow outcome of the cases in which they are born.

What would government look like in the new era conservatives envision? It might mean a slim, even shriveled administrative state, with thousands fewer regulations and smaller agencies that focus more on enforcing than making rules. But we will still have clean water and air and safe highways. Rather, it will be Congress that will have to enact and take responsibilities for the policies, rather than delegating to unaccountable agencies. While those agencies shrink, Congress may have to staff up in order to pass more laws. And while Congress will have to legislate many of the details previously left to bureaucrats, the laws will represent greater political consensus, and better technical policy making, for having to run the gantlet of House, Senate, and presidential approval.

Alternatively, Congress and federal agencies could stay as they are. But instead of agencies promulgating regulations with the force of law, agencies could instead transmit complicated and technical proposals for laws (in the place of regulations) for Congress to pass without Congress having to dot an i or cross a t. In either case, government will become more transparent and accountable, as policy making returns to the branches whose members must run for election by the people.

This brave new world—which is actually a return to pre-1937 government—would also mean that ordinary Americans won’t get sandbagged by agencies that are allowed to do as they please by overly deferential courts. The judiciary is unlikely to see much of a change, however, because this new world probably won’t increase the quantity of litigation in federal courts. It will just mean that deciding any one case will take a little more work.

In short, we might start to live in a republic that again resembles the Framers’ original design.

Of course, turning back the administrative state will require far more than one year’s set of Supreme Court cases. It may well require more than just the Supreme Court too, but also the cooperation of the president and Congress over the course of decades. But this year calls to mind Winston Churchill’s announcement of the British victory over the Germans at El Alamein in November 1942. “Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” So too 2019 may well be remembered as the year that—at the least—marked the end of the beginning for the administrative state.