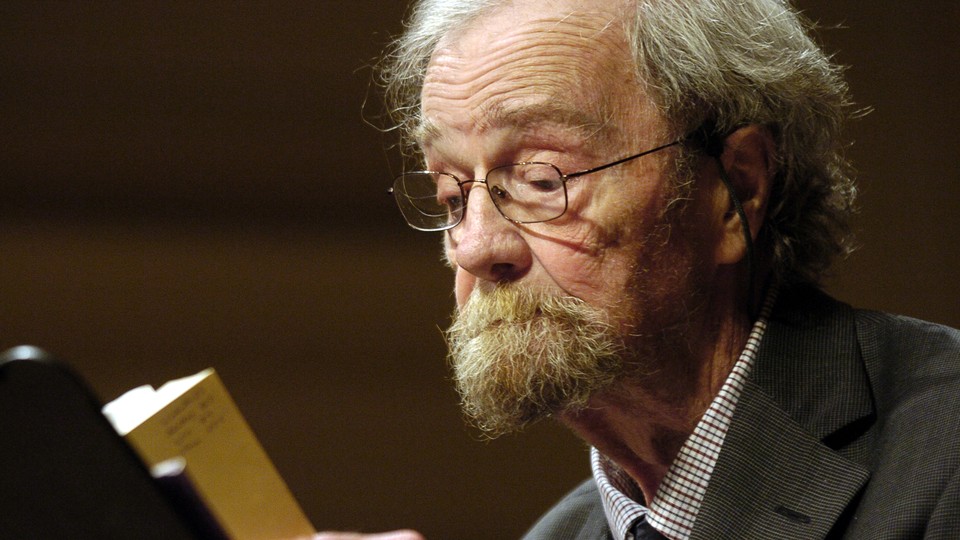

Remembering Donald Hall, a Poet of Love and Loss

The writer, who died at 89, invested common words with the power of a constructive, shaping force.

The death of Donald Hall comes at a moment when his poetry feels newly relevant. Hall’s hospitable poems, which approach difficult ideas in the idioms of common speech, defend the sense and meaning of ordinary language from the daily barrage of a debased and weaponized English. At a time when straightforward “tough talk” is giving popular license to open racism, sexism, and anti-intellectualism, Hall’s poetry instead revels in the surprising insights of trivial observations and confronts the anguish of ubiquitous death and loss.

A poet’s personal life offers irresistible fodder for interpretation, and Hall’s has been no exception. Hall, who moved from a faculty position at the University of Michigan to a New Hampshire farmhouse in the mid-1970s, where he lived until his death on Saturday, has often been regionalized as a New England farmer-poet with “barnyard credibility” and nostalgic impulses.

These descriptions shrink the breadth of Hall’s work—as most attempts to categorize a poet inevitably do. The majority of his poems would not make sense to someone looking for a poetry that celebrates rural life or mourns its passing. Instead, Hall captures, with a directness of speech, the contradictions of physical being and abstract thought, intricate form and commonsense questioning, very much present in American lines of poetry stretching from Anne Bradstreet and Edward Taylor through Emily Dickinson.

In Hall’s hands, a word like memory, which could so easily be a cliché in a poem, takes on an unusual radiance. Here are the first and the final stanzas of the early poem “September Ode”:

And now September burns the careful tree

That builds each year the leaf and bark again

With solemn care and rounded certainty

That nothing lives which seasons do not mend.

…

The young are never robbed of innocence

But given gold of love and memory.

We live in wealth whose bounds exceed our sense,

And when we die are full of memory.

Hall’s point is that what seem to be losses—the fall, growing up—are in fact gains, since they come with the “gold” of autumn’s leaves, which is also the metaphorical wealth of accumulated memory. To make this claim, he uses some arresting contrasts: robbed/given; innocence/love; live/die. And he poses those antitheses against a pair of repeating sounds: innocence/sense; memory/memory. The unexpected way that the word memory returns, in the final line, becomes somehow more surprising, and more satisfying, than another rhyming word might have been.

American poets have often believed that ordinary varieties of speaking can address much of what matters in knowledge and in thought. Poets of the mid-20th century, like Adrienne Rich or Amiri Baraka, critically examine and revolutionize ways of thinking about gender, sexuality, and race, but their ideas are expressed in language that’s accessible to a broad readership.

Hall’s poems demand, similarly, to be understood by the reader—not to retreat from the understanding. They take the measure of the blank confusion of reality by rendering more vivid and comprehensible the terms available to understand it. It’s common for many readers to come to poetry with the wary expectation of looking for “deeper meaning.” In Hall’s poetry, the meaning is often quite obvious; it’s the surface—that constellation of sound, image, and syntax—that requires more attention.

There are lines of Hall’s poems whose music has stayed in my head for years, evidently incapable of ever being dislodged: “December, and the closing of the year”; “And now September burns the careful tree”; “Exiled by death from people we have known.” Three lines of three different poems, but with the same memorable up-and-down iambic rhythm and the same number of syllables.

This particular choice of poetic meter has helped poets to capture many different kinds of reactions to the world, providing a type of reusable container for sorting things out and arranging them together. For Hall, the two-beat iamb tolls the relentless melodies of departure from the world: a great-uncle early on; his grandfather; his father. “Poetry begins with elegy, in extremity,” he writes.

So it might be unsurprising that, when the poet Jane Kenyon, who was married to Hall for 23 years, dies of leukemia, the beat of Hall’s poetry grows a little fainter, as though heard from a little farther off. And the poems, especially in the collection Without (1998), themselves become looser, more diary-like, newly tied to the rhythms of living in grieving memory:

When it snowed one morning Jane gazed

at the darkness blurred

with flakes. They pushed the IV pump

which she called Igor

slowly past the nurses’ pods, as far

as the outside door

so that she could smell the snowy air.

In this spare finale to a poem titled simply “Her Long Illness,” the structure of the poem is muted: blurred, Igor, and door provide a rhyme that holds the stanza together with the barest murmur of resemblance. The earlier poems show a certain confidence in straining ideas about the world through a sieve of words. This poem gently sounds out what it sees, unwilling or unable to risk strong claims about its significance.

When Hall does make a claim about life, he does it to welcome the reader into the poem, rather than to set up an initial challenge for the reader’s understanding. “To grow old is to lose everything,” a poem called “Affirmation” begins. The pleasure in reading a line like this one is not to feel the browbeating of certainty—certainty here seems besides the point, since there’s nothing particularly new in the idea that age brings loss. Instead, such lines offer the chance to inhabit familiar descriptions of the world, at least initially. In that sense, his poems, though they grapple with the deepest personal loss, also face outward. Seizing on commonplaces as prompts for further thinking, Hall’s poetry enters into the world in which such statements are made and circulated. The claims made by the lines serve as a kind of starting place that might bring readers together.

What’s more, Hall’s images work like this too: They create a picture of the world to live in and watch as it becomes more elaborate, then fades away. Poetry, at least shorter lyric poetry, departs from the novel in the quantity of trust that it demands from its readers. The kinds of declarations Hall’s poetry makes are more like affirmations than assertions. Poetic lines can give the reader something to lean against for a little while.

Hall was particularly good at propping up things, ideas, and sounds to see how well they lasted. In this sense, the poems might, after all, be tied, with only a slight leap in imagination, to the decades he spent at Eagle Pond. Not in the sense of a hokey rural wisdom, but rather in the sense of a careful craftsmanship or artisanship, with the values of work and revision that Hall maintained were essential for poets.

Now that Hall is gone, it would be tempting to search his elegiac poems for consolation. But that is rarely what elegies, or poets, aim to provide. Instead, his poems invest common words with the power of a constructive, shaping force. When language becomes an accomplice to affliction and pain, poetry like Hall’s offers, as a kind of response, the sense of a meticulously built object, a reminder of connection and mutual reliance in times of despair and confusion.