Eilen Itzel Mena was the first in her family to navigate the American post-secondary education system. An artist born to Dominican immigrants in the Bronx, Mena was raised by her grandparents, who drilled into her from an early age that higher education was her clearest pathway to success.

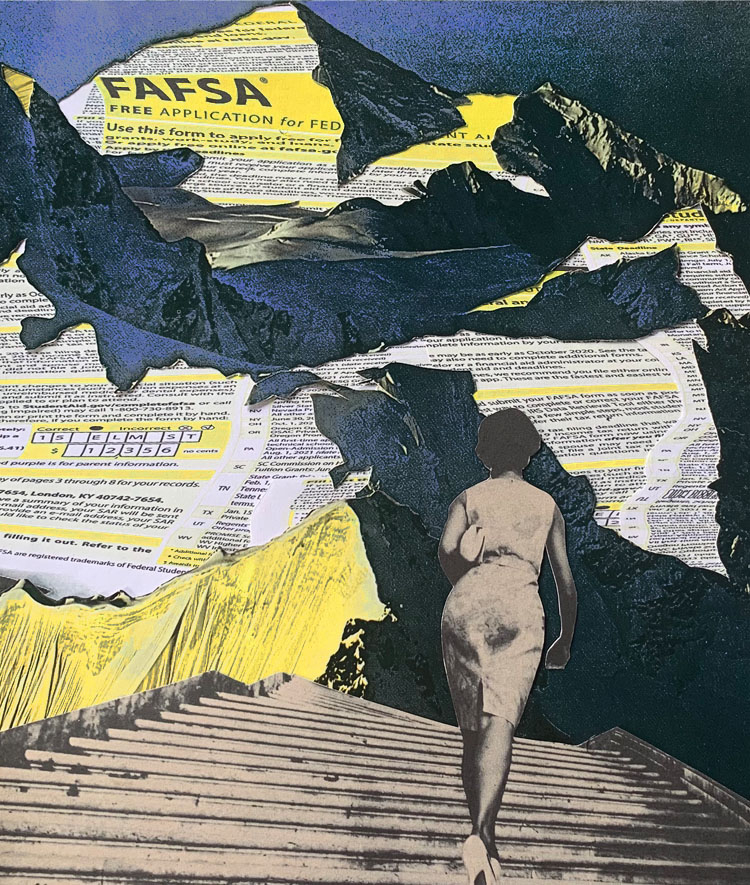

At 18, she applied to the fine arts program at the University of Southern California—her top choice—and was accepted with a full scholarship. But after making the cross-country move on her own (her grandparents would only be able to afford to visit once, at graduation), and just one day before classes were set to begin, Mena received some unfortunate news: She already owed $15,000 to USC’s financial aid office. The scholarship covered her tuition, but the rest of her expenses—including the pricey supplies and software necessary to complete her coursework—was her responsibility. With her grandparents unable to help, Mena’s only path forward was to apply for federal financial aid. The Free Application for Federal Student Aid—or FAFSA, as it’s known—is a tedious, byzantine process that requires applicants at U.S. institutions to provide a laundry list of documents, from tax returns to records of assets and untaxed income to bank statements and more. For some, this process is an immediate barrier. Often, those who are most in need of aid have a complex relationship with the labor market, and they may not feel comfortable exposing their financial histories to a standardized system. First-generation applicants coming straight out of high school, meanwhile, lack a full financial history and therefore don’t have the required documents, which, in turn, affects how much they are able to receive. “I know people who applied for financial aid and didn’t get enough,” says Mena. “They had to get private loans to subsidize that.”

Things get more complicated for “nontraditional” applicants, such as working adults whose prior post-secondary learning was affected by loans, debt, and the responsibility of raising children. This term also applies to learners with undocumented parents—undocumented students are not eligible for federal aid—along with those who work part-time, work on contract, or are part of the gig economy. For these learners, tracing a full financial picture is a daunting task: Precarious employment may not offer proper documentation that helps establish financial history and credit, making it difficult to apply for loans of any kind.

None of this is particularly new. FAFSA has been routinely criticized for its anachronistic application criteria—and, as a result, for failing to account for the needs and realities of many aspiring students, including older applicants, children of immigrants, those at risk of homelessness, those living with severe or permanent disabilities, living in foster care or in situations that don’t fit FAFSA’s stringent definition of legal guardianships, and many others. But by and large, the system is functioning exactly as it was designed to—and that’s the problem.

In 1965, when the government first introduced a federal financial aid program for post-secondary education, the majority of learners in the U.S. were white. Black citizens were effectively barred from attending universities, via systemic discrimination and state-sanctioned violence, unless those schools were built and led by Black scholars. And while students who attended Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) were legally allowed to apply for financial assistance prior to 1965, they often faced strong resistance from both state and federal officials. At the time, Black people had a better chance of being drafted for war than receiving federal aid.

Some positive changes have been made to the federal aid program over the years—including the Middle Income Student Assistance Act of 1978 and the addition of PLUS Loans in the early 1990s, which made it possible for parents to take out loans on their children’s behalf—but the need for simplified, equitable access to financial aid for learners with nontraditional backgrounds remains abundantly clear.

One of the more promising innovations to enter this space is a technological solution: a chatbot designed specifically with vulnerable students in mind and with a goal of demystifying and democratizing the FAFSA process. The brainchild of Salesforce.org, Impact Labs—a community-rooted collective to collaborate on technology solutions that can potentially assist in addressing the most urgent social inequities—has been developing the chatbot app for the past nine months, and it is being masterminded by experts in education policy, technology, and design. A lack of urgency regarding FAFSA accessibility, and the limits of existing programs to properly assist “nontraditional learners,” was the driving force behind its development.

The app developers cite a heightened conversation design as critical to the chatbot’s promise. Leveraging a type of communication that replicates and predicts human conversation via artificial intelligence, the chatbot can help simplify terminology that may be confusing, like the difference between a bursary and a loan, or the definition of a promissory note. Giving applicants a clear understanding of key FAFSA terms helps ensure that they don’t miss application deadlines, and students can receive much-needed financial assistance at a faster rate.

“For us, today’s students are not your 18- to 21-year-old whose parents pay their way and they finish on time,” says Dominique Raymond, an Impact Lab expert and strategy director at Lumina Foundation. “They’ve got kids, they’ve got jobs. And so the chatbot questions really focused on who are actually today’s students.”

The project experts consulted students throughout the development process, and lived experiences played a fundamental role in informing the way in which the chatbot will function. To account for the diversity in learners’ school-life balance, the questions inputted were more reflective of students’ realities:

”How far do you live from campus?”

“Are you working?”

“Do you need childcare?”

Paired with the real-world prompts, the bot is also designed to be especially helpful for learners whose parents don’t speak English as a first language.

“In sociolinguistics, they are called ‘language brokers,’” Greg Bennett, a sociolinguist and the director of conversation design at Salesforce, says of this feature. “How could we make the content that shows up in that chatbot accessible and easier to translate and easier to communicate from party to party?”

Mena didn’t have the benefit of the chatbot when she went through the FAFSA application process. She couldn’t even share the nuanced details of the process with her grandparents because of the significant language barrier. As a nontraditional learner, she faced another steep obstacle: The system forced her to apply as an individual adult because her grandparents weren’t her legal parents (according to FAFSA rules, only a student’s “biological or adoptive parents” are deemed legal guardians). This designation does not include relatives such as grandparents, aunts, uncles, siblings, and cousins, unless they have adopted the dependent. Why does this matter? A recent study discovered that more than 3 million children in the U.S. live with their grandparents, and about 400,000 of those are between the ages of 15 and 17. All of these are prospective students who are at risk of falling through the cracks, as Mena almost did. At just 18, she had to cobble together a financial history based on her extremely limited employment up to that point. As she puts it, “You’re considered a lone wolf.”

Douglas Reed, who teaches government studies at Georgetown and is the director of the university’s master’s degree program in Educational Transformation, has seen firsthand how decades of policy and negligence have shaped the way students of color engage with the financial aid system. He describes the language used throughout the application process as “invasive” and “stressful.” “It’s a system based on distrust,” he says. The original architects of FAFSA had a very narrow idea of the type of student who would be applying for aid, he explains: “One who is from a nuclear household that has two parents that are conventional wage earners, who filed their taxes in a particularly orderly way.

“Just navigating that whole process requires an enormous amount of information, an enormous amount of assistance. Particularly for folks who are first-gen college students,” he adds. Luckily, Mena did have some help: a trusted middle school teacher who, in high school, had helped with the paperwork for a series of grants that allowed her to attend a prestigious Connecticut boarding school. When Mena was an undergrad student, that same teacher co-signed her loans, effectively taking on the burden of repayment if Mena defaulted.

While Mena’s family chipped in what they could to help her financially—at one point her grandparents pawned their heirloom jewelry—she would send a portion of the aid money she received back east to help with household expenses, and to her siblings. Her grandfather passed away earlier this year, but health problems had limited his capacity to work for some time, forcing her grandmother to take several jobs, first as a server in a seniors’ home and later as a beauty sales associate. “Whenever I got bigger grants at the beginning of the year, I would send them money,” she says. “Any amount helped.” This is yet another reality that our current aid system completely misses. Providing financial support for parents and extended family is par for the course for many students, particularly those from Black and brown communities, and this setup often follows them long after they have graduated.

In the coming five years, FAFSA is set to undergo a massive overhaul that will likely affect low-income families and marginalized learners, and the chatbot’s open-source content repository—propelled by Salesforce.org technology—will support efforts to integrate those larger revisions in real time, benefitting all those who use the bot and contribute to the content. “Our goal is that anyone in our community can continue to contribute to the content of the chatbot,” says Cheryl Timoney, vice president of tech for social impact at Salesforce.org. Institutions that use Salesforce and deploy the bot for free within their platform learn from it and modify the app based on their own students’ usage trends.

It’s been four years since Mena graduated from college, and despite her scholarship and federal aid, she accrued more than $30,000 in debt. Most of that sum went toward housing and food. Some went to help support her family. Throughout her academic journey, she juggled two or more jobs on top of her academic load.

A solution that simplifies the mechanics of FAFSA and uses simple terminology would have helped Mena during her application process, saving her hours of emotional stress and confusion. But she maintains that FAFSA requires a robust reimagining if its systemic shortcomings are to be corrected. “It has to be policy changes,” she says.

And those changes must be substantial, because ultimately very few learners have a former teacher willing to co-sign their loans—an act of such exceeding generosity that Mena still gets choked up. “If I think about that too much,” she says, “I’ll get emotional.”