Richmond’s Confederate Monuments Were Used to Sell a Segregated Neighborhood

Real-estate developers used the statues on Monument Avenue to draw white buyers to a neighborhood where houses could not be sold “to any person of African descent.”

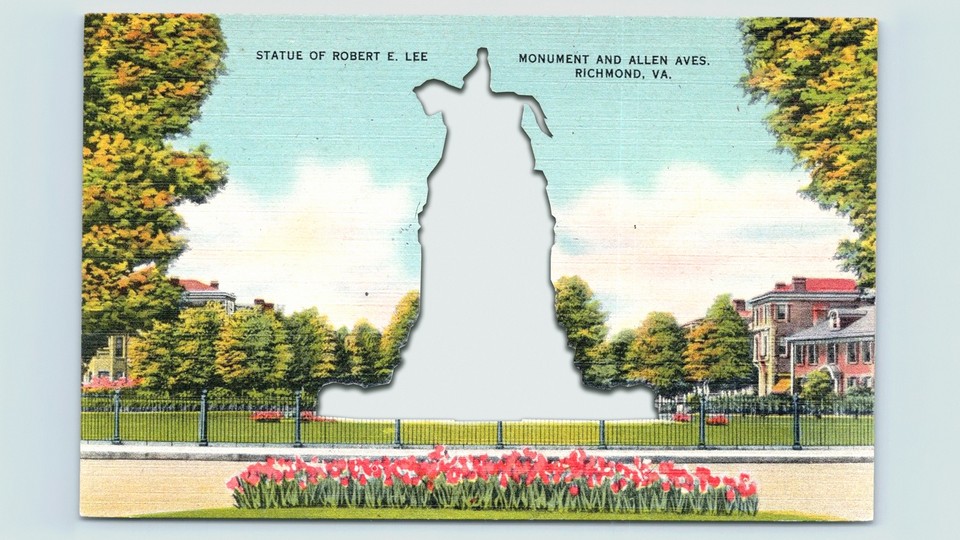

On May 29, 1890, roughly 150,000 people gathered for the dedication of the Robert E. Lee monument in Richmond. It was an opportunity to celebrate a man who many believed embodied the virtues of the old South, the “Christian Warrior” who bravely fought to the bitter end for the Confederacy’s Lost Cause. The Richmond industrialist and former Confederate staff officer Archer Anderson predicted that the monument would continue to teach “generations yet unborn,” and that it would “stand as the embodiment of a brave and virtuous people’s ideal leader!”

It was also an opportunity to showcase a new real-estate development that included wide boulevards and Monument Avenue itself—a divided boulevard, 140 feet wide, featuring parallel rows of trees along its center and another row lining the housefronts. The neighborhood was developed exclusively for white residents. Eventually, the avenue would feature monuments to Lee, “Stonewall” Jackson, and J. E. B. Stuart; to Confederate President Jefferson Davis; and to the Confederate official Matthew Fontaine Maury.

The Confederate monuments dedicated throughout the South from 1880 to 1930 were never intended to be passive commemorations of a dead past; rather, they helped do the work of justifying segregation and relegating African Americans to second-class status. Monument Avenue was unique in this regard. While most monuments were added to public spaces such as courthouse squares, parks, and intersections, Monument Avenue was conceived as part of the initial plans for the development of the city’s West End neighborhood—a neighborhood that explicitly barred black Richmonders.

By the turn of the 20th century, civic leaders in Richmond and elsewhere embraced the economic vision of a “new South” led, according to the historian Reiko Hillyer, by a “rising class of businessmen and industrialists who owed their growing economic power to alliances with northern business interests” and who “sought to promote an era of national reconciliation and a climate favorable to business and industrial expansion.” These men—bank presidents, manufacturers, lawyers, and real-estate developers—purchased lots and built impressive homes along Monument Avenue.

Throughout the development of the neighborhood, real-estate companies used the monuments to entice buyers. In 1913, the Greater Richmond Realty Company took out an ad in the Richmond Times-Dispatch that included an illustration of the proposed Jackson monument under the headline: “Stuart, Lee, Davis, Have Already Been Honored. No Longer Neglect Jackson.” The depiction of the intersection along with a tree-lined field in the background made it easier for potential buyers to envision their home overlooking the Confederate general. The ad implied that Jackson would not be fully honored until all the lots were claimed and occupied.

Real-estate companies also reassured potential buyers through restrictive covenants that “no lots can ever be sold or rented in MONUMENT AVENUE PARK to any person of African descent.” This was a reassuring message for white Richmonders during a time of unrest and uncertainty. Business and civic leaders worried about labor activism among the city’s black tobacco workers and elsewhere during this period of industrial expansion. Many still recalled with horror the brief but consequential period from 1879 to 1883, in which a biracial party known as the Readjusters controlled the wheels of government throughout the city and state. Large numbers of black Virginians voted, attended public schools, and were elected to local and state positions, all under the leadership of the former Confederate general William Mahone.

Black leaders remained politically engaged, even after the Readjusters were forced from office. In response to the dedication of the Lee monument, the Richmond Planet editor John Mitchell Jr. asserted: “The South may revere the memory of its chieftains. It takes the wrong steps in so doing, and proceeds to go too far in every similar celebration. It serves to retard its progress in the country and forges heavier chains with which to be bound.” Those chains were at work in the dedication and in the development of a new and modern neighborhood that bound black Richmonders to underdeveloped neighborhoods, such as Jackson Ward, that lacked sewer lines, water mains, regular garbage collection, and paved streets.

In addition to private restrictive covenants that ensured only white families would reside in the shadows of Lee, Jackson, Stuart, Maury, and Davis, the city of Richmond passed a number of discriminatory ordinances, including one in 1911 that restricted African American residents to those city blocks in which they already constituted a majority. In 1929, the city passed another ordinance that, relying on Virginia’s newly adopted “racial-integrity law,” prohibited a person from living in a neighborhood where he or she was prevented from marrying any member of the majority population.

These restrictions all but guaranteed that most of the neighborhood around Monument Avenue would remain exclusively white for decades, and it also brought into sharp focus the racial and political inequities for black Richmonders. “I cannot go on Monument Ave.,” Robert Leon Bacon wrote to the governor of Virginia in 1955, “and visit a white girl for fear of being ‘lynched’ or beaten up or arrested or electrocuted.” Bacon called for “colored people to rise up and demand our rights and first class privileges, as citizens should always have.”

Black Richmonders slowly won those rights in the following decades. The city council began to more accurately reflect Richmond’s racial diversity, Virginia elected its first black governor in 1989, and then came the first serious attempt to alter Monument Avenue, in 1996, with the dedication of the Arthur Ashe monument. One local newspaper columnist, Michael Paul Williams, wrote in anticipation of the dedication that the monument to the tennis icon and philanthropist would “fit quite nicely” alongside Lee, Davis, Jackson, Maury, and Stuart, but he also cautioned that the “two warring viewpoints are difficult to reconcile, even after more than a century.” He was right.

The additions of new monuments to the city’s commemorative landscape, including a slavery reconciliation memorial, a statue honoring teacher and businesswoman Maggie L. Walker in downtown Richmond, and the recent dedication of Kehinde Wiley’s Rumors of War statue, just blocks from Monument Avenue, have not defused a belief shared by many that these Confederate monuments still symbolize and reinforce long-standing and deeply embedded racial and political inequities.

The recent decision by Virginia Governor Ralph Northam and Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney to remove Monument Avenue’s Confederate monuments offers an opportunity to reshape these public spaces into something that reflects the collective values of all its residents and a place where all Richmonders feel welcome.

In the days following the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, demonstrators tagged the statues lining Monument Avenue with various messages that underscore their connection to the long history of racial and economic inequality in this country.

The Lee monument, in particular, has become a gathering spot for local activists, many of them African American, who have found creative ways to reclaim and appropriate the site to further their cause. In fact, it is not a stretch to imagine that more black Richmonders have set foot on Lee Circle over the past two weeks than in the past 130 years combined.

Young African American activists now speak passionately on a range of issues from the monument’s base to the crowd, while others register people to vote, all under the watchful gaze of a man who was willing to give his life to a cause that sought to prevent this very outcome. Two 14-year-old ballerinas transformed the monument into a stage, and even an impromptu graduation ceremony was held. At night, the image of Floyd, along with the messages “Black Lives Matter” and “No Justice, No Peace,” is projected onto the Lee monument.

And on Wednesday night, activists toppled the statue of Jefferson Davis. The old order is crumbling.