/media/video/upload/20210909_GoldTeeth_Video_Final_01.mp4)

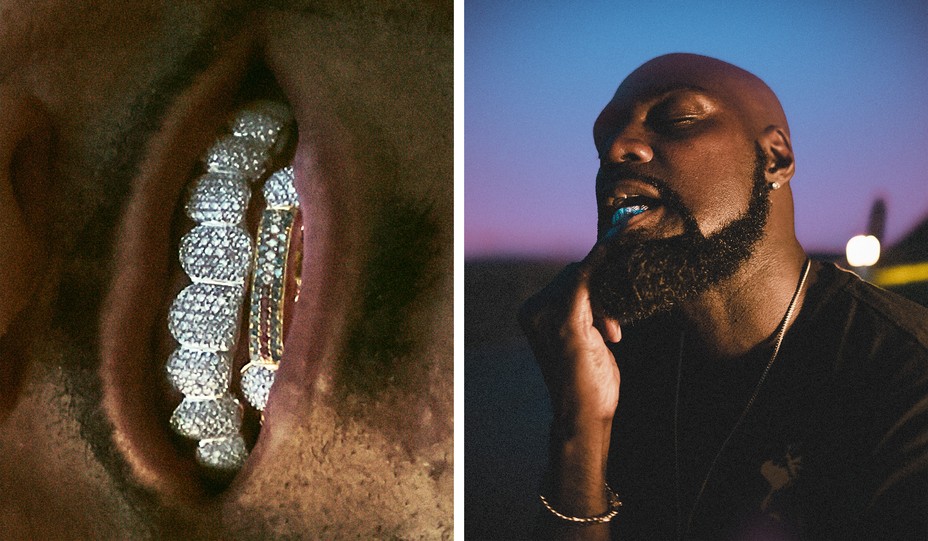

Gold Teeth Are Beautiful on Their Own Terms

Grills are more than adornment. They’re about Black agency.

There’s a poem most Black people know, and even if you don’t know it, at one time or another you’ve lived it or seen someone you love live it.

It’s a poem by Paul Laurence Dunbar called “We Wear the Mask,” his seminal ode to how Black folks must show one face to the world and another to ourselves. The verse begins, “We wear the mask that grins and lies” and tells a Black American story, about what it feels like to be treated like a problem.

This, too, is a story about that, but it’s also about gold teeth and grills, two words for mostly the same thing: a beauty we chose together, the grin that wears a mask all its own.

Samiah Rahim, 28, a certified diamontologist in New York, has two golds, commissioned from a jeweler she met at a party in 2019. One is a window around her right canine, the other a gap filler between her two front teeth. Front gaps are common in Rahim’s family. She figured the best way to honor the gap was to pour gold into it. Her gap filler did its job—it sits between Rahim’s front teeth in a rectangle of light. Without knowing it, Rahim was continuing a tradition that has existed for nearly 3,000 years.

The earliest people to decorate their teeth with precious metals or gems were likely the Etruscans, who wore gold in their teeth as early as 700 B.C. Mayans drilled holes into their teeth to insert jade, a gem with spiritual significance that was considered more valuable than gold. Around A.D. 1300, people in the Philippines decorated their teeth with gold along with practicing other forms of tooth modification, including intentionally blackening their teeth.

How this aesthetic spilled into American Black culture is not clear. But by the 1980s, when golds had already been a staple of dentistry practice for decades, the gold teeth of the rappers Rakim and Slick Rick and of the boxer Mike Tyson gained a national spotlight. Today, celebrities such as Beyoncé, Nicki Minaj, and Chris Paul wear grills as a fashion accessory, their mouth glimmering.

“I tell you what,” says Michael Scott, 65, a dentist in Lexington, Kentucky, who told me he’s been practicing dentistry for 28 years and putting on golds for just as long. “When we want to shine, we want to spend more than anybody else.” A removable grill might be $200, Scott told me. But clients who opt for multiple permanent gold crowns might spend several thousand dollars.

Every gold tooth in a Black mouth is a song with no lyrics. I think of how Rochelle Younge, at only 13, draped one of her healthy teeth in gold. Born and raised in St. Louis, Younge had a best friend who was being taken by her mother to get a gold tooth put in, and so they resolved to do it together. Both of them got the crown placed on the left side, matching, each adorning their smile with a slice of the other. I listen to Younge, now 64, speak about this and think of how often I’ve looked at a gold tooth and seen a kind of North Star, a light that chants “home.”

Related podcast: The short, uneven history of Black representation on television—from Julia to The Cosby Show to today’s “renaissance”

Listen and subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google Podcasts

According to Scott, gold is the best restorative material there is, malleable yet unlikely to fracture once set, allowing for a better marriage between the crown and the biological tooth. Of course, there are some things not even gold can heal. In the early 2000s, Younge decided that it was time to part with the gold tooth that had been in the top left of her mouth for decades. After years of working the front office of a warehouse, she had had enough of the stereotyping that came with wearing a gold tooth. The final indignity came in 2003, when a Black supervisor took it upon himself to tell her, “You know, that gold is really going to keep holding you back.”

She would need to take out the beauty she’d chosen years ago in order to be selected for the job she deserved. Today, Younge’s gold tooth sits in an envelope, among some of her other prized possessions. It was replaced with a porcelain model. When I ask what became of her friend, she laughs. They haven’t spoken much in the past 10 years but, as far as she knows, the friend still has the matching gold crown installed. Maybe this is also what draws me to gold teeth—not merely the idea of masks but the intimacy of being the same kind of beautiful as someone you love, of choosing that mask together.

In the mid-’90s, Al Gilles was a high schooler looking to reinvent the gap in his smile. He got a couple of gold teeth, but they were poor quality. There weren’t many craftsmen around who could do the gold correctly. The jewelers of the ’90s, according to Gilles, knew little about the culture of inner-city kids in New York. They didn’t understand that gold was more than shine, he told me—it was part of a lifestyle. His best friend, Jean Midi, enrolled in a trade school for dentistry and began making gold teeth; he offered to make two custom-fitted ones for Gilles. Gilles is now a manager and lead mold fitter at UndergroundGrillz in Brooklyn, of which Midi, in his mid-40s, is the founder and owner.

Among Black folks, gold teeth have become as much a matter of community as of style. This tradition of ornamentation and healing has lent many Black folks the opportunity to be seen by one another, and the culture built around it continues to grow. I think of Gilles and Midi treating UndergroundGrillz not only as a storefront but as a training ground where they oversee Black and brown jewelers. And I think of what it means to have jewelers who come from the culture, teaching a new generation to give others what Gilles received in the ’90s: a chance to be beautiful on his own terms. I consider all of this, what it means that you can dress your whole mouth like the sun and snap it off at a moment’s notice, and I think of how beauty, at its best, is a form of agency.