The Photographs That Made Me Feel Less Alone

Garry Winogrand captured ordinary groups of unknown people in all their beauty, humanity, and radiance.

When I was young, the beauty of church always belonged to other people: the believers. They saw the same stained glass I saw, but when its jeweled light cut their skin into kaleidoscopic colors, they somehow belonged in that light in a way I never would. They could feel the lilt and soar of the hymns as truth, as collective yearning, as a tin-can telephone connecting them to God. That’s what I told myself. I told myself I was alien to that beauty—I’d never be anything but an interloper lurking just outside its grace.

Some version of that girl I’d been in church—with legs too long for her denim overalls, and palms covered with half-moon crescents where she’d dug her nails into her skin—was summoned for a different rapture, years later, by the photography of Garry Winogrand. Some version of that girl was told: This is beauty you belong in. The first time I entered the Brooklyn Museum’s 2019 exhibit of his color photography, part of its force was this immediate sense of invitation, as if a door had been carved in a wall, leading to some new world, and now I could cross into it—or perhaps simply see more clearly that I’d been living in that miraculous world all along. It had only disguised itself as something familiar, or banal.

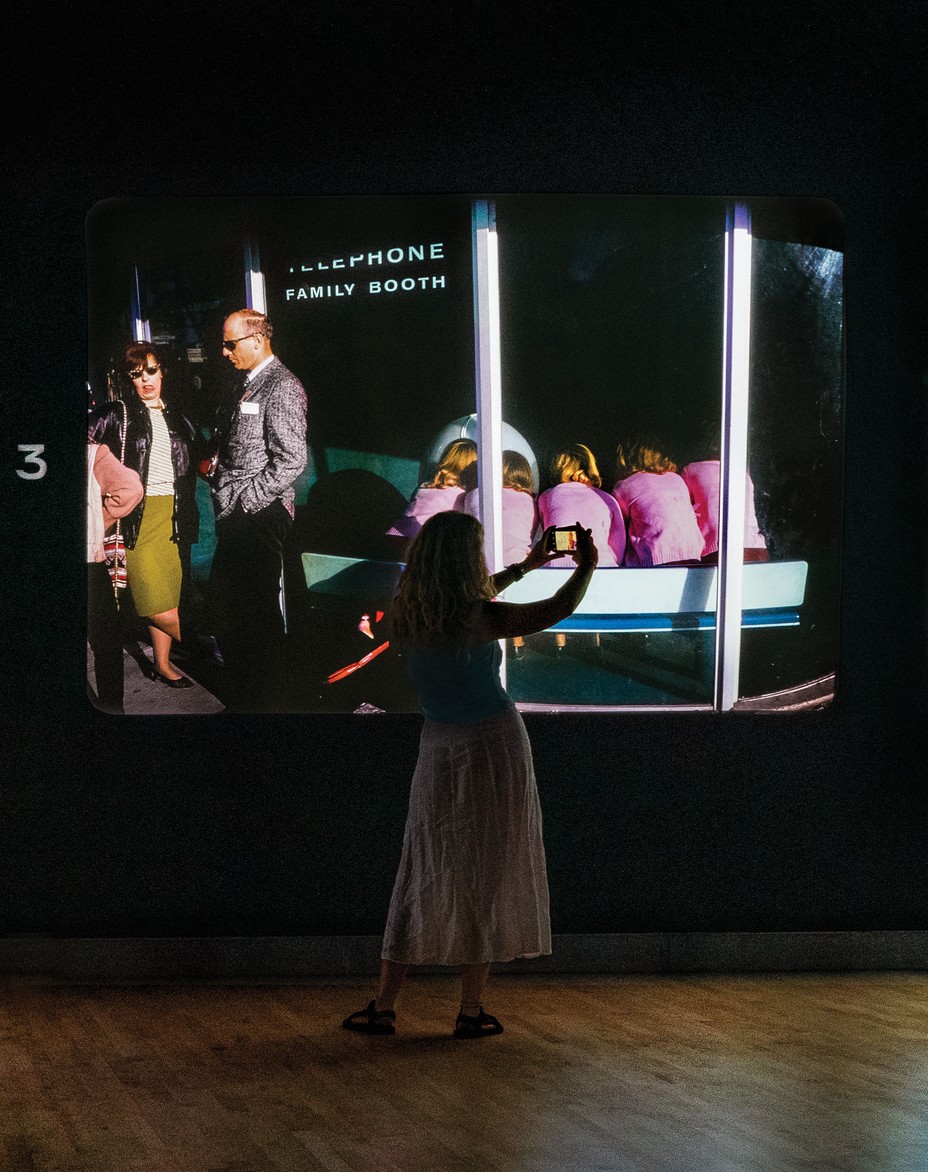

Even the physical structure of the exhibit contributed to this sense of invitation—induction into some holy ordinary realm, hidden in plain sight. At the entrance, you had to part a thick black-velvet curtain to step into a long gallery that was as cool and dark as a cinema, with huge color slides projected on the walls: a dark-haired teenage girl in a white bathing suit silhouetted against a bright-blue sky. A little boy in tiny shorts putting his coins into a vending machine to buy a Coke. Old ladies in folding chairs on the sand, playing cards. A woman propped on her elbows on her beach towel, a messy mickey stick-and-poke tattoo on her arm, cat’s-eye sunglasses hiding her mood. A man lying on his back, with his blue-canvas sneakers tucked beside him and the sunlight pouring across his body, the cigar in his mouth pointed straight up toward the sky. These photographs seemed born of a gaze that regarded strangers with faith—in their beauty, in their humanity, in their radiance—and suggested a radical innocence, almost transgressive, in an era when the country has often felt divided past the point of repair, certainly past the point of goodwill.

Winogrand was deeply drawn to public spaces—sidewalks, bus stops, airports, beaches, motels, campgrounds, highways, boardwalks, carnivals, zoos, parking lots, pools—and his photographs opened onto these restless, gritty infinitudes, often landing on a single wistful or bewildered or determined individual amid the larger crowd. The exhibit, steeped in the moods and fashions of the 1950s and ’60s, felt like time travel: women in chiffon scarves, men washing their Mustangs, people dressed in their Sunday finest for the airport, or their bathing caps for the beach. It was easy to follow these accents of the era into nostalgia for another time—a time when daily attention to the glorious undertones of the mundane had been possible, and justifiable. But of course this unremarkable glory is still everywhere, all around us. It still lives in precisely those in-between moments the photos captured, in all their incandescent immediacy: people smoking alone on the sidewalk, or leaning their head against another’s shoulder. People showing off, goofing off, getting off flights. People reaching for each other on threadbare towels laid across the scorching sand.

Years prior, during my early attempts to get sober—when I was spending many evenings each week in church basements—I’d fallen in love with a quote from the writer and theologian G. K. Chesterton:

How much larger your life would be if your self could become smaller in it; if you could really look at other men with common curiosity and pleasure … You would break out of this tiny and tawdry theatre in which your own little plot is always being played, and you would find yourself under a freer sky, in a street full of splendid strangers.

Now here it was, this dark gallery with its windows of light: a freer sky, a larger theater, a street full of splendid strangers. These slides were a tutorial in the proximity of the sacred, how it was never far from us: a family having a picnic against a backdrop of rolling white sand dunes; street clowns at a parade beneath a sign advertising dallas’ finest hamburgers; flight attendants in their powder-blue suits, clustered on an asphalt divider, shadowed by palm trees and boxy, off-white airport hotels. These ordinary strangers literally gave off light. It glowed across the faces of the ordinary strangers watching them. The exhibit felt like a recovery meeting. It felt like going to church. I couldn’t get enough of it.

After my first visit, I kept coming back. I must have visited that exhibit at least 30 times. Mostly, I went with my baby; it was, among other things, a useful way to pass the hours of our days. But I brought everyone I could. I wanted to be there with my friends, my friends’ babies, my mother, my aunt, the ex I hadn’t spoken with in years. I wanted to bring my grandmothers back from the dead, so I could be there with them. It was a secular cathedral, a church of regular life, this dark room lit by luminous slides. They lined the walls like stained-glass windows, but instead of showing saints or biblical scenes or the stations of the cross, they showed daily existence: two kids flipped upside down on a handrail above a storm drain; a man in a striped shirt licking a cone of vanilla soft serve, that moment of pleasure like a whittled point of stillness inside the frenetic circus of Winogrand’s hustle and bustle.

These were stunning scenes not because they were extraordinary, but because they weren’t. They were full of ordinary people seen so clearly that they became extraordinary in their beauty. “How do you make a photograph that’s more beautiful than what was photographed?” Winogrand once asked. But I didn’t see his photos that way. I didn’t think he was making the world more beautiful; I thought he was excavating beauty that was already there. His alchemy didn’t turn the world holy so much as it revealed that the world had been holy all along—outside the doors of the museum, and inside them too, we were holy. That was part of the grace of his work, how it suggested that anyone could be art, that the people standing in that darkened room were no less radiant than the people glowing on the walls in front of them.

Born in the Bronx in 1928, Winogrand was a New Yorker at his core, though he also described himself as a “student of America,” and often crisscrossed the country on road trips, taking photographs of gas stations and rest stops and motel pools and highways. He disliked the terms street photography and snapshot aesthetic, but it’s not hard to see why people use these terms to characterize his photos, which suggest immediacy and spontaneity, capturing fleeting moments of the present tense in their frames. Winogrand initially studied painting at Columbia University, but “found painting a slow, deliberate process that demanded lots of patience,” as his friend Tod Papageorge put it. “He preferred to work in a way [that] could convulsively seize what it described … Photography answered his agitated sense of self.”

Looking at Winogrand’s photographs of the open roads and beaches of America, its motels and airports, and especially the crowded sidewalks of its most populous city, I found myself thinking of Walt Whitman, who had roamed the streets of his beloved island of Mannahatta a century earlier. Maybe Whitman found his own answer to an “agitated sense of self” in his peculiarly radical vision of expansiveness—his feeling of effusing into others, and feeling them effuse into him, a faith both ecstatic and arrogant. Whitman certainly felt composed of strangers. His 1860 poem “To a Stranger” addresses itself to them:

Passing stranger! you do not know how longingly I look upon you,

You must be he I was seeking, or she I was seeking, (it comes to me as of a dream,)

I have somewhere surely lived a life of joy with you …

You give me the pleasure of your eyes, face, flesh, as we pass.

Winogrand’s photos are saturated by this fascination with strangers—this faith in the strange rub of molecules between anonymous bodies, and the fantasies we spin from the faces of others. If Winogrand considered himself a student of America, then that Brooklyn gallery was a rhapsodic articulation of the curriculum he’d been studying. It was organized into eight themed clusters, like textbook lessons: “Coney Island,” “Early Color,” “In the Streets,” “Portraits and Still Lifes,” “On the Road,” “Travel,” and, in the back, facing each other: “Women” and “White Masculinity.” Though he was mainly known for his black-and-white photographs, Winogrand produced more than 45,000 color slides during the ’50s and ’60s—making slides was less expensive than making prints—and it feels essential and deeply moving that the photos weren’t turned into prints for the exhibit. As slides in rotation, more than 450 in total, they felt warmer and more alive, more in motion.

“Sometimes I feel like … the world is a place I bought a ticket to,” Winogrand once said. “It’s a big show for me, as if it wouldn’t happen if I wasn’t there with a camera.” Many of his photographs document the rapt or wary faces of people absorbed by some pageantry or performance that is unseen, out of frame: a crowd gathered in a bruised-blue dusk around a garbage can labeled clear lake, let’s be neat, all pointing at something in the sky—fireworks? shooting star?—or four women standing in front of a carnival lemonade stand, looking fascinated and perhaps a little repulsed. We cannot see what they are looking at, only their faces doing the looking. Winogrand was less interested in the spectacle itself, and more interested in what happened to us when we beheld it. How it gathered us. That gathering—in the shadows of the carnival booth, the asphalt parking lot beneath the fireworks—was what he’d bought a ticket to: the show of our wonder and discomfort, our yearning for enchantment.

When I first stepped onto Winogrand’s street of splendid strangers, I’d been separated from my husband for four months. I was fond of saying that I lived on Planet Women. It felt as if all the men had been banished from my life, or at least from my days. Perhaps that was part of why I often found myself sitting at the far end of the Winogrand exhibit, my back turned on the section called “White Masculinity,” hopelessly entranced instead by the women across from it, as if these women were a refuge, a solace, a womb: a woman with a bouffant on a bar stool, sitting between a slot machine and what appears to be a Jack and Coke; another one solo at a grimy diner table, hunched over a plate of eggs and toast. Something in me reached toward the woman smoking alone in her convertible, with the sun setting behind her and the wind whipping her hair. She made solitude look liberating, while others made it look like a grind; I knew the truth everyone knows, which is that it’s both.

Looking at those women, I kept thinking of something my friend Jake had written about walking up and down First Avenue in the weeks after his best friend’s death: “On the streets of New York the trances of strangers’ lives were written on their faces. I felt like I was everyone’s mother, and that everyone was mine.” I kept thinking: These women are all my mothers. Maybe that sounds absurd or melodramatic, but something about the cool, dark room stirred these wild surges of emotion. Its luminous panels opened my nerves to the unknowable inner lives of people I would never meet, and its shadows obscured the embarrassing sentiment displayed across my features whenever I projected too much onto the projections of their fleeing bodies.

If Winogrand was a devoted chronicler of public spaces, then during the many hours I spent in that shadowy hall—close to the sweat of strangers, to their morning breath, to their invisible daydreams, their untold anguish, their ordinary restlessness—I felt the exhibit itself becoming another kind of public space, our bodies assembled in that room, giving one another our eyes, our faces, our flesh. We were an iteration of the gatherings illuminated on the slides around us: the cluster of folks sunbathing by the pool of the Tally Ho Motel, or the ad hoc community pooling in the shadows under the Coney Island boardwalk—a mom with her toddler sleeping on her lap; a shirtless man doing pull-ups on the wooden rafters, someone else’s laundry hanging behind him. Or the three women in bathing caps and bloomers standing in the surf, facing away from the camera, gazing at the swimmers farther out, beholding that revelry and yet not fully immersed in it. Those of us in the gallery found ourselves in some version of that purgatory as well—at once drawn in and kept on the fringes. As Whitman once wrote: “Both in and out of the game and watching and wondering at it.”

Since my separation, I’d been seeking solace in public places—had spent pockets of that aching winter in the Russian baths tucked behind Coney Island high-rises and the ones in an old tenement basement on Tenth Street. Placing my body in those unbearably hot rooms alongside the bodies of other people whose names I’d never know was a way to remember heat during that long, frigid season. In the spring I took my baby on long walks around Prospect Park, past the smoking charcoal bricks and sizzling hamburgers of strangers, as she rode like royalty in her stained and fraying baby carrier, close to my heart. When we got home and I lifted her back onto the floor—where she could actually stand, breaking my heart and remaking it—the dampness of her back and the dampness of my chest were matching continents of sweat. The residue of our bodies in proximity was a faint echo of the months when there had been no skin between us at all.

On the subway that summer, I found myself leaking tenderness toward the unknowable strangers sitting across from me, playing Candy Crush on their cellphones and picking up their kids’ dropped Popsicles. Someone in a church basement quoted Plato: “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle,” which was not actually something Plato said. It was something a 19th-century Scottish minister said, but the urge to make the sentiment ancient or immutable made me love it even more. In any case, it seemed suddenly clear to me that everyone on the Q train during rush hour was fighting a hard battle, and so was everyone in the unbearable heat of underground saunas, and I wanted to tell each and every one of them, I know you are fighting! And you! And you! Instead I took myself to Winogrand, over and over again. His photographs were daydreams. Or rather, they were a technology for daydreaming. They were spurs to spin stories about the lives of the people he’d preserved in their frames: three men carrying a rolled-up rug into an apartment building; a hand with pink nail polish reaching for a glazed cruller.

“There is nothing as mysterious as a fact clearly described,” Winogrand said, and his photographs perform some version of this seduction by way of plain exposure. “That’s all there is, light on surface,” he also said, which made me think of a deceptively simple statement Edward Hopper had made about his own art: “What I wanted to do was paint sunlight on the side of a house.” John Szarkowski, a former director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art and one of Winogrand’s great champions, once said that his photos were “not illustrations of what he had known, but were new knowledge.” It’s true that his photos gaze not toward the legible but toward what’s still being discovered, though I have always experienced them less as knowledge than as frames placed around unknowing. They do the work James Baldwin called for when he said, “The purpose of art is to lay bare the questions that have been hidden by the answers.”

That pink-nailed hand reaching for the glazed cruller—who did that hand belong to? What joy was her indulgence celebrating? Or else what consolation was she seeking, for what pain? Or perhaps the pain in that photograph was not hers but mine. Perhaps Winogrand’s photos invite us not only to imagine the lives of strangers but to respect the ways these imagined lives are also, always, projections of our own. We are perpetually finding in the face of another person whatever jigsaw piece—foil or mirror—fits our needs in that moment. When his photos capture crowds, they always mind the gap: They recognize what we can’t know about the people around us, and the ways in which crowds are just collections of discrete solitudes.

Winogrand is often understood as a photographer of crowds rather than of isolation. “Winogrand seems so contrary in spirit and style to Edward Hopper,” the critic Geoff Dyer writes in The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand. “Hopper is the painter of loneliness, emptiness and isolation, motionlessness; Winogrand is busy, manic.” Yet Dyer keeps mentioning Hopper when he writes about Winogrand, and I think he’s onto something. Part of the brilliance of Winogrand’s photos—part of what they understand about what it means to be alive, among other lives—is that the line between being lonely and being surrounded is porous, and the states are often simultaneous. In one photo, an elegant woman stands on a sidewalk full of men—in her black dress, with her black gloves, a circle of white pearls around her neck, her solitude like a bubble on that crowded street. Winogrand’s Coney Island photographs are particularly deft in their evocation of the ways we are alone in crowds: the man smoking in the dappled shade and sunlight beneath the boardwalk, surrounded by the blurred bodies of others; a boy’s face close-up, his cheeks and jawline caked with sand, someone else’s feet disembodied behind him. Solitude is not the opposite of public gathering, but one of its constituent threads. A public space is nothing more than a collection of opaque faces, each one a mystery of loss and longing, like a silent disco—strangers listening to different songs, all their bodies dancing together.

On Winogrand’s street full of splendid strangers, people kept disappearing. This was part of the exhibit’s design—every horizontal slide clicked to a new one after eight seconds, every vertical slide after 13 seconds—and there was excitement and frustration and pathos in their rotation. It replicated the flux and flow of the public spaces Winogrand documented, the way strangers rise like visions and then flee from our sight; the way someone might get off the subway just as we’ve started to build a story to explain her puffy eyes: her secret affair, her broken heart, her sick child. “The woman in the yellow swimsuit looks like you!” my friend whispered in my ear, but by the time I looked up, she was gone. When I raised my cellphone to capture two people wearing foil sunbathing collars—looking like flowers in a kid’s play, their faces framed by golden petals—they’d already disappeared before I could pin them in place, trap them for good, make them my own.

If Winogrand’s strangers kept fleeing, perhaps that’s why I kept returning—so I could keep finding them again. More than any other museum exhibit I’ve ever seen, it was one I was hungry to come back to. The photos kept revealing new layers: How many times had I seen that couple embracing on a towel before I noticed the rough layer of stubble lining the inner curve of her armpit—that sudden intimate shadow? And how many times did I see the bronzed man doing a handstand at the beach—balanced on the supine body of another man lying across the sand—before I noticed how their hands were clasped together, their fingers interlaced?

The exhibit, on display from May to December, held—like a long exposure—the ways my life changed in that time. On our first visit, my daughter sat quietly in her stroller, still a baby sucking her two fingers. By early fall, she’d become a busy toddler, full of plans—she wanted to run around the exhibit, to grab the pen I was using to take notes. She no longer wanted to observe the energy of these photographs; she wanted to embody it, channel it, claim it for herself. The exhibit took me from early separation to the horizon of divorce—as if marking the time I spent crossing the long hillside of that pain. Winogrand had taken many of the photographs I was looking at in the midst of his own divorce, bringing his children on outings to the New York Aquarium and the Central Park Zoo. I felt I could see the ghost of this backstory in his zoo photographs—in particular, how they held pain and wonder side by side. Szarkowski saw in these zoo photos proof that Winogrand could find beauty even in cloistered or sorrowful places: “His appetite and affection for life is so great that even this scarred and crippled version of it is capable of moving him to sympathy.”

On days when I found myself simmering with resentment, locked in endless internal arguments—the kind you keep litigating, even if you know you can’t win them—I’d take my daughter to Winogrand and let the world get large around my anger. That felt more possible than “letting go” of it, and certainly more possible than resolving it. I could just show up in the hallway of strangers and let them surround it. In recovery, people like to say, “Sometimes the solution has nothing to do with the problem,” and Winogrand’s photographs had nothing to do with my problems. They just reminded me of the ordinary, infinite world—how it was still there, waiting. How do you make a photograph that’s more beautiful than what was photographed? This spring, his photos asked me to believe there was a more beautiful version of everything, even the ugliest, messiest struggles—if you could just regard them from the right angles, crop them the right way, capture them at the right moments, recognize the core pulse of their humanity.

Though for many months I kept my back to the men in the “White Masculinity” section, I eventually turned to look at them too, in all their pathos and fallibility, their bruised and blustering egos: men in suits, men at football games, men smoking and taking photos of flowers and gazing at naked mannequins in a store window. An elderly man with his head thrown back, laughing. Ha! And I was actually happy for him, for whatever he was laughing about.

Once, I was kneeling beside my daughter’s stroller, feeding her Cheerios to keep her quiet for a few more moments, and it felt so right to be on my knees in that darkened room—as if I were praying to the sunlight glowing on the skin of all these ordinary human animals. Every one of them was fighting a great battle.

The first time I came to Winogrand without my daughter was on Mother’s Day. Sunday was the afternoon each week that she spent with her father. Missing her was a primal sensation: I could feel my heart beating toward hers, across town, toward her seashell toes, the wispy brown curls at the back of her neck, her Cheerio breath. Her absent stroller felt like a phantom limb. At the museum entrance, I reflexively went to the special stroller door. The lobby was full of mothers with their children. The world was full of babies whenever mine was somewhere else.

The Winogrand exhibit was full of babies that day, too: a tattooed hand holding a baby in a sky-blue coat; twins in a double pram, in matching white hats and matching white blankets, their matching blue eyes staring wide—staring at me. A toddler in the park held a baby doll of her own. Everybody wanted her baby close! Other photos held the girl my daughter might someday become: a girl hoisted up to see a city parade, with long, coltish legs and double-buckled Mary Janes; a girl drinking a Coke in the shallow end of a swimming pool.

Missing my daughter was a bottomless feeling. I’d never needed art so badly as I needed it that day. I needed to be delivered from myself, back into the richness of the world; needed to be reminded that beauty could surprise you, that it was lurking in the strangest ruts and crevices—a tray of relish dishes gleaming in the sun, a huge parking lot skirting the base of snow-capped mountains. The faces on those walls were faces I would never know—faces that were no longer themselves, that were 50 years older, or else dead—but they’d be part of me forever, in their sublimity and anonymity, preserved in the amber of the spring and summer’s ache. Sometimes the solution has nothing to do with the problem, and missing my daughter was not something to be solved. It was something to be met with stunning, unspeakable, regular beauty, and then left intact—pain living behind the radiance, its shadow and also its spine.

This article appears in the December 2019 print edition with the headline “A Street Full of Splendid Strangers.”