I. A Broken Office

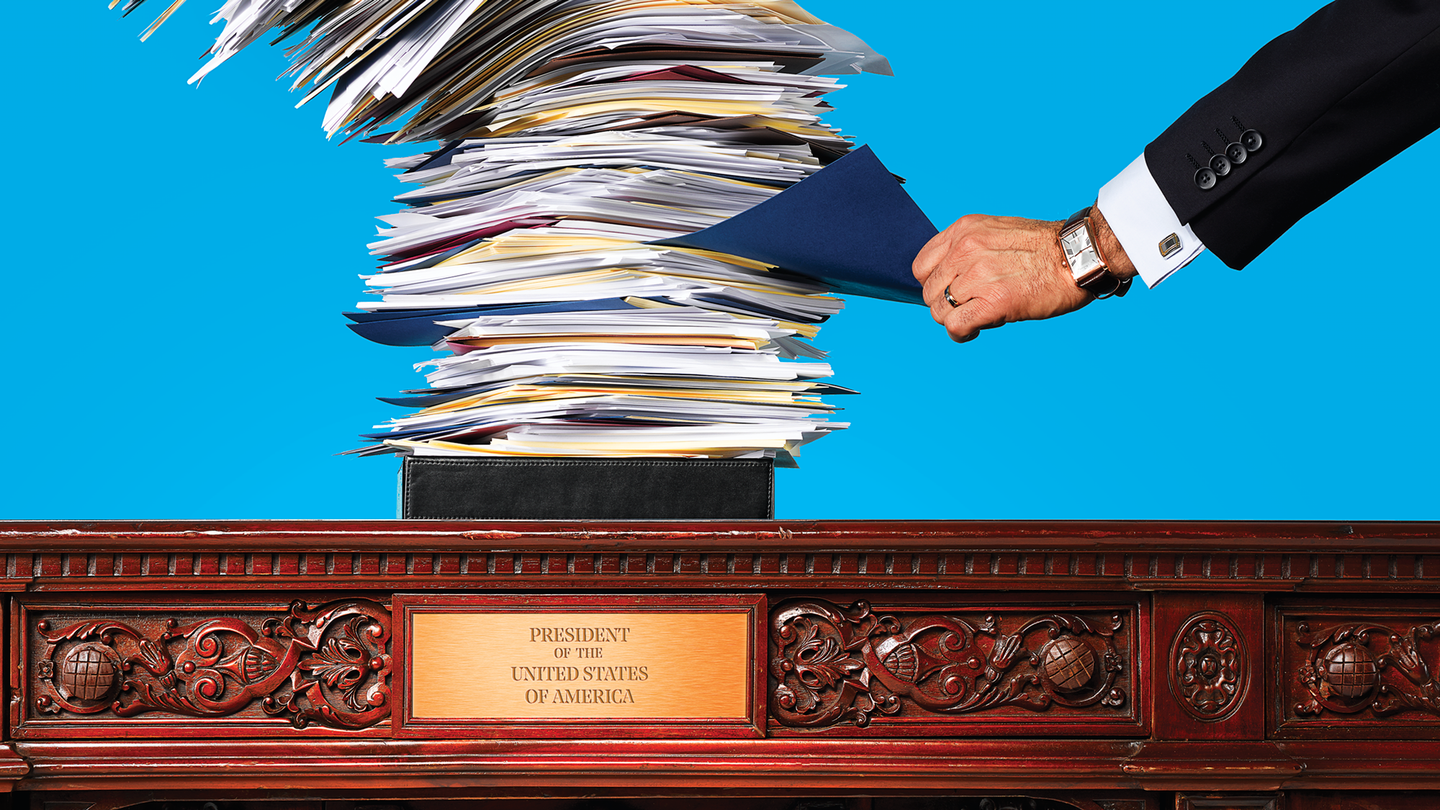

Donald Trump often appears to be a president in rebellion against his office. A president, we have come to expect, hastens to the scene of a natural disaster to comfort the afflicted. After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, President Trump arrived tardily and behaved unseriously, tossing rolls of paper towels at storm-battered residents as if he were trying to drain three-point shots.

We have come to expect that when the national fabric rends, the president will administer needle and thread, or at least reach for the sewing box of unity. After white supremacists marched through Charlottesville, Virginia, shouting “Jews will not replace us,” President Trump’s instinct was to emphasize that there were good people among the neo-Nazis.

We expect presidents to be deal makers. Even when the opposition has calcified, they are supposed to drink and dine with the other side and find a bipartisan solution. Trump promised that his decades in the real-estate business would make him an especially able negotiator, but on health care, taxes, and immigration, he hasn’t much bothered to trade horses with Democratic lawmakers. Not even Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia—up for reelection in a state Trump won easily—was seriously approached as a negotiating partner.

To his critics, Trump’s detours from the expectations of his office prove he is unfit to inhabit it. Or they demonstrate his hypocrisy: The man who now ignores the traditional responsibilities of the job was once perhaps the nation’s foremost presidential scold, regularly criticizing his predecessors when they responded to a disaster inadequately or played too much golf or couldn’t make a deal. Trump even suggested that Barack Obama’s manner of descending the stairs of Air Force One was unpresidential.

Members of maga nation scoff at the president’s detractors, and bask in the glow of the burning norms. Why should Trump throw all his energy and political capital into producing quick results in Puerto Rico when the island’s poor planning and weak infrastructure have made success impossible? Why should he bow before Democrats who will never work with him anyway? Trump’s backers see him as a new kind of president, unburdened by political correctness and unconstrained by the old rules of Beltway deal making. He doesn’t let niceties get in the way of taking care of business.

The intensity of public feelings about President Trump makes it hard to measure him against the presidency. His breaks with tradition are so jarring, and the murmuration of tweets so thick, that debate about his behavior tends to be conducted on the plane of propriety and the president’s seeming disregard for it.

If Trump were a less divisive figure, we might view these lapses differently. We might consider that what looks like incompetence or impertinence on the part of the officeholder could also be evidence that the office itself is broken.

Many of the responsibilities that vex Trump are ones that were not part of the job’s original design. They have accrued to the presidency over time, most in the recent past. The Framers, fresh from a successful rebellion against a tyrannical king, envisioned an executive who was limited in power and even stature. For a good long while, the design held. James K. Polk’s wife, Sarah, was so concerned that the 11th president might enter a room unnoticed, she asked the Marine Band to play “Hail to the Chief” to get people to turn their head when he arrived.

Today we notice when the president doesn’t show up. We are a president-obsessed nation, so much so that we undermine the very idea of our constitutional democracy. No one man—or woman—can possibly represent the varied, competing interests of 327 million citizens. And it may be that no man—or woman—can perform the ever-expanding duties of office while managing an executive branch of 2 million employees (not including the armed forces) charged with everything from regulating air pollution to x-raying passengers before they board an airplane.

Even the role of commander in chief, already one of the weightiest presidential responsibilities, has grown rapidly in its demands. National security is today threatened less by slow-moving armies than by stateless terror groups who might weaponize a rented truck and by rogue states who might weaponize an email. Rare is the day when one or more of these enemies don’t present an imminent danger requiring the president’s attention. “The modern presidency has gotten out of control,” Leon Panetta, who has served past presidents as the White House chief of staff, the secretary of defense, and the director of the CIA, told me recently. “Presidents are caught in a crisis-by-crisis response operation that undermines the ability of any modern president to get a handle” on the office.

The growth of presidential power is not new. When Arthur Schlesinger Jr. published The Imperial Presidency, in 1973, the term was already at least 10 years in use. But the office hasn’t just grown in power; it’s grown in scope, complexity, degree of difficulty. Each time a president has added to the job description, a new expectation has conveyed, like the Oval Office furniture, to the next man in line. A president must now be able to jolt the economy like Franklin Roosevelt, tame Congress like Lyndon Johnson, comfort the nation like Ronald Reagan.

Video: The Broken Presidency

The emotional burden of these responsibilities is almost unfathomable. The president must endure the relentless scrutiny of the digital age. He must console the widow of a soldier he sent into combat one moment, and welcome a championship-winning NCAA volleyball team to the White House the next. He must set a legislative agenda for an often feckless Congress, navigating a partisan divide as wide as any in modern American history. He must live with the paradox that he is the most powerful man in the world, yet is powerless to achieve many of his goals—thwarted by Congress, the courts, or the enormous bureaucracy he sometimes only nominally controls. “In the presidency there is the illusion of being in charge,” George W. Bush’s former chief of staff Joshua Bolten told me, “but all presidents must accept that in many realms they are not.”

Even Trump, not one to readily admit a mistake, has acknowledged that he underestimated the difficulty of the job. “I thought it would be easier,” he told Reuters 100 days into his term. A blunt admission—and one much mocked by his critics—but one every president eventually makes. Lyndon Johnson made the point in his earthy way: “The office is kinda like the little country boy found the hoochie-koochie show at the carnival,” he said. “Once he’d paid his dime and got inside the tent: It ain’t exactly as it was advertised.”

President Trump is tackling some of the challenges of the office. He has tallied up partisan victories: cutting taxes, appointing conservative jurists, and slashing regulations. He has also shed responsibilities in a job that traditionally only accumulates them, neglecting allies, his own employees, and even the oldest presidential aspiration, telling the truth.

Whatever you think of him, Trump is rewiring the presidency—or perhaps more accurately, dismantling the machine and flinging the parts onto the White House lawn. Given Trump’s priorities and attention span, it may fall to his successor to put it back together. But you might be grateful to him for demonstrating, in his inimitable way, the extent to which the machine has become a wheezing and jerry-rigged contraption badly in need of repair. Or, if you can’t bring yourself to be grateful, you might consider this: The flaws in the presidency also made a President Donald Trump possible—he was an emergency solution to the problems that had tripped up his more conventional predecessors.

Either way, until we fix the office, presidents will continue to be frustrated by its demands, and Americans will continue to be disappointed in their leader. We will enter another presidential-campaign season desperate for a good outcome, but unprepared to choose someone who can reset the terms of success.

Over the past year, I’ve conducted interviews with political scientists, historians, dozens of men and women who have worked in the West Wing under presidents of both parties, and some of the men who had the often unenviable job of sitting behind the Resolute Desk. What they described is an office in dire condition: overburdened, unrelenting in its demands, and unlike anything the Founders intended when they designed the role 230 years ago.

Before his inauguration, Barack Obama discussed the office he was about to assume with his predecessor, George W. Bush. “Ultimately, regardless of the day-to-day news cycles and the noise, the American people need their president to succeed,” Bush told him. Americans still need their president to succeed. But the presidency has set him up for failure.

II. An Ever-Expanding Job Description

On April 8, 1938, more than 100 demonstrators dressed as Paul Revere marched along Pennsylvania Avenue. Some carried signs that read we don’t want a dictator. They were protesting the Reorganization Act, the first major modification of the executive branch since the presidency was created, in 1787. The legislation was an outgrowth of the Brownlow Committee, which Franklin Roosevelt had commissioned to study the presidency and update it for modern times. The conclusion from the final report: “The president needs help.”

Roosevelt responded by requesting a handful of personal aides and a reorganization of his Cabinet departments. “The president’s task has become impossible for me or any other man,” he said. Roosevelt’s predecessor and archrival, Herbert Hoover, supported him in the request.

Congress and the public, however, objected. In an April 1938 Gallup poll, only 18 percent of the country thought the president should have more power. Three hundred thirty thousand Americans sent telegrams to members of Congress denouncing “one-man rule.”

The Democratic majorities in Congress denied the Democratic president’s plea for help—a rebuke nearly impossible to imagine today. In a fireside chat, Roosevelt promised to work to defeat in the 1938 election any Democrat who had blocked him. He failed badly; all but one candidate he backed lost. After a year of fighting, Congress finally granted the president some additional manpower. To dispatch the duties of his office, he would now be allowed six assistants and given the power to reorganize the executive branch within certain limits. Congress reserved the right to veto any of the president’s plans for further modifications.

The emergencies of the Great Depression and, later, World War II gave Roosevelt more leverage with Congress, and the gains he made for the executive branch not only increased its power but provided a blueprint for his successors to do so further. In the 80 years since Roosevelt got his six additional men, the executive branch has steadily increased in size and power; Congress and the public have grumbled plenty about power grabs by presidents from the other party, but offered little resistance of the type witnessed on Pennsylvania Avenue in 1938. “Congress chose to abdicate by choosing not to govern,” the NYU public-service professor Paul Light says. “It has totally acquiesced to the White House,” enabling its own diminishment.

The Congress-centered government of the Framers’ conception has thus shifted to one dominated by the executive. Today, about 400 people work inside the White House, in jobs from national-security adviser to public liaison to special assistant for financial policy. Two thousand more work in the Executive Office of the President. In 1940, the civilian agencies of the federal government employed 443,000 people. They now employ three times that number. Roosevelt’s vice president and Cabinet of 10 could join him for a group picture behind his Oval Office desk. The 24 members of the Trump administration with Cabinet rank have to be photographed from across the room to fit in the camera frame.

A White House once quaintly understaffed is now overstaffed, which leads to laborious decision making and palace intrigue. Even in administrations less chaotic than Trump’s, traffic jams at the Oval Office door are routine. “The guys around the president want to show their stuff. They want him to look at my program, look at my issue,” says Joseph Califano Jr., who served as the chief domestic-policy adviser under Johnson and also as Jimmy Carter’s secretary of health, education, and welfare. “So many issues get to the president’s throat that shouldn’t really get there”—issues “better left down in the bureaucracy to resolve.” Aides who don’t get the attention they want gripe, then leak. The insatiable, never-resting media take those leaks and turn them into new headaches for the West Wing team.

Even so, you might think that extra manpower would be a boon to an overextended president. But unlike a chief executive in the corporate world, a president can’t delegate. Some, such as Carter, have tried. It didn’t end well. In July 1979, he held a Cabinet meeting that was more like the Red Wedding. He had come to believe that the people he’d appointed were being disloyal and “not working for [him], but for themselves.” Some pushed back, saying they were simply advocating for their policy positions. But the press has a way of describing debate as discord. Carter concluded that because a president is on the hook for every decision his administration makes, decisions of any import must be made not by the Cabinet secretaries but in the White House, where the president’s political team can vet them. So he brought more decision making into the West Wing—lengthening the line at the Oval Office door, and shortening everyone’s temper. “You’re lucky you were fired,” a friend told Califano, a victim of the bloodletting. “You’d have never been able to stand being strangled by the White House staff.”

Dwight Eisenhower was a life-hacker. During his military career, he devised systems that made him more efficient. After he became president, he applied his methods to the already vast management challenge. When Ike first entered the executive mansion, the story goes, an usher handed the new president a letter. “Never bring me a sealed envelope!” he said. Nothing, he explained, should come to him without first being screened to see whether it really merited his attention.

Eisenhower sorted priorities through a four-quadrant decision matrix that is still a staple of time-management books. It was based on his maxim “What is important is seldom urgent, and what is urgent is seldom important.”

Sage advice, but antique for any president trying to manage the office after the attacks of September 11, 2001. The Cold War presidents monitored slow-moving events that had flashes of urgency. Now the stakes are just as high, but the threats are more numerous and fast-moving. From North Korea alone, the president faces both Cold War–style nuclear devastation and cyberwar mayhem. Michael Morell, a former deputy director and acting director of the CIA who briefed the previous four presidents, told me: “There have never been more threats than there are today.”

Presidents now start their day with the President’s Daily Brief, an intelligence assessment of the threats facing America. How the PDB is delivered changes with each president. Early in his term, Trump reportedly requested a verbal digest of the brief. During the Obama years, the PDB was wrapped in a stiff leather binder and looked like the guest book at a country club. Inside was a grim iPad containing all the possible ways the president could fail at his most essential role. Satellite photos tracked terrorists’ movements, and pictures of failed laptop bombs demonstrated the pace of awful innovation. At the end of the briefing with intelligence officials, a president might be asked whether a specific person should be killed, or whether some mother’s son should be sent on a secret raid from which he might not return.

John F. Kennedy requested that his intelligence briefing be small enough to fit in his pocket. Since 2005, the PDB has been produced by an entirely new entity in the executive branch, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, which itself includes several intelligence agencies founded since Kennedy’s era, among them the vast Department of Homeland Security.

Monitoring even small threats can take up an entire day. “My definition of a good day was when more than half of the things on my schedule were things I planned versus things that were forced on me,” says Jeh Johnson, who served Obama as homeland-security secretary. An acute example: In June 2016, Johnson planned to travel to China to discuss the long-term threat from cyberattacks. Hours before takeoff, he was forced to cancel the trip so he could monitor developments after the shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando.

“The urgent should not crowd out the important,” says Lisa Monaco, Obama’s chief counterterrorism adviser. “But sometimes you don’t get to the important. Your day is spent just trying to prioritize the urgent. Which urgent first?”

One of George W. Bush’s staffers remembers the president’s basic conclusion about the attacks of 9/11: “ ‘My fundamental job was to protect the American people, and I didn’t do it.’ ” After the attacks, then–CIA Director George Tenet added a threat matrix to the president’s morning briefing that delineated all possible threats of terrorist activity. Bush wanted to go through every one. “After 9/11, we woke up every day behind,” says Bush’s communications director Dan Bartlett. “Every day was catch-up day.”

Each administration worries that it might somehow slip and let an attack through. This leads to a lot of make-work and ass-covering, impediments to managing any organization. In his book The Test of Our Times, Tom Ridge, the first homeland-security director, recalled such an episode. Prior to the 2004 U.S. elections, Osama bin Laden released a taunting videotape. Ridge said some Cabinet officials wanted to raise the nation’s threat level to show that the administration was being vigilant, even though they had no new evidence of a specific threat. “Is this about security or politics?” he asked himself.

After weighing matters of life and death at the appointed hour, the president can expect to be interrupted later in the day by unanticipated chaos. When Lisa Monaco was new on the job, she got a taste of the pace of things: One Monday in April 2013, the Boston Marathon was interrupted by horrific bombings, setting off a manhunt that paralyzed the entire metropolitan area. The next day, an envelope addressed to a member of Congress containing the toxin ricin was discovered. On Wednesday, an explosion destroyed a fertilizer plant in West, Texas.

One national-security official, describing the pace of events during the Obama years, said it was a relief when healthcare.gov crashed, in 2013. It meant that a different kind of crisis had interrupted the permanent cycle of security management in the age of terror. The threat of attack still loomed, but with attention elsewhere the requirement to participate in homeland-security theater for a nervous public was, momentarily, diminished.

When disaster does strike—whether the work of an enemy or an act of God—the theatrical role presidents play is amplified. It’s not enough to monitor or even manage the federal government’s response. He has to dash to the scene. We now expect the president to be a first responder, too.

So ingrained is this expectation that we forget how recently it took hold. In 1955, a number of strong storms battered the United States, but Eisenhower was barely mentioned in the newspaper stories about Hurricanes Connie, Diane, or Ione. That hurricane season was then the costliest on record, but there are no pictures of the former Allied Commander pointing at maps or receiving furrowed-brow briefings from meteorologists. When some of the storms hit, Ike was on vacation. His absence was not the subject of endless concerned punditry, as it would be today. “We get a little more sleep around Washington,” Vice President Richard Nixon told a reporter writing a whimsical piece about the president’s time off during one of the storms. “He has the ungodly habit of getting up early.”

Eisenhower wasn’t callous. Local governments, civil-defense forces, and the Red Cross were supposed to stack the sandbags and distribute relief when a storm hit. Upsetting that division of duties, the president believed, would jeopardize core American values. “I regard this as one of the great real disasters that threatens to engulf us, when we are unready as a nation, as a people, to meet personal disaster by our own cheerful giving,” Ike said in 1957. “Part of the reason is this misunderstanding that government is taking the place even of rescuing the person, the individual, and the family from his natural disasters.”

Lyndon Johnson believed in a stronger connection between the people and their president—a belief that would expand the role for all the presidents that have come since. In September 1965, after Hurricane Betsy hit New Orleans, Johnson visited the masses huddled in the city’s George Washington Elementary School. “This is your president,” he declared. “I am here to help you.” Johnson spoke of the duties of the national family. “In times of distress,” he told disaster officials, “it’s necessary that all the members of the family get together and lay aside any individual problems they have or any personal grievances and try to take care of the sick mother, and we’ve got a sick mother on our hands.”

After visiting victims of the storm, Johnson leaped into action, coordinating local forces and pushing Congress to fund relief. The Washington Post rewarded Johnson with the headline “LBJ Sees Betsy Toll in Hundreds: Assumes Charge of Day and Night Relief Operations.” A president lives for that kind of press.

Rushing to the people’s aid suited Johnson’s politics. The trip to New Orleans was a Great Society house call, a dose of attention that mirrored the president’s legislative agenda aimed at helping the needy. It was also a bit of self-promotion well suited to the times. Families across the country were watching the drama of the storm unfold on the news during the dinner hour. Networks binged on images of Americans waist-deep in water, fishing their heirlooms from ruined living rooms. Television, according to Gareth Davies, an American-history professor at Oxford University who has studied the evolution of the president as first responder, greatly accelerated the demand for the president to appear front and center.

When Johnson visited Indiana to tour tornado damage, a skeptical columnist writing for the South Bend Tribune wondered why a president should interrupt people trying to put their lives back together. The author then had a revelation, praising Johnson for “a demonstration of personal Presidential concern.” He continued: “The Presidential visit briefly transforms the institution into a symbol, a person to be seen and spoken to,” providing evidence to victims that “somebody cares,” thereby raising their “distressed spirits.”

Popular expectations of the presidency were changing, and not just when a storm hit. The bigger the federal government became, the more a president had to act as a warming face of that distant behemoth—and its avatar on TV. “In the ’60s, expectations exploded,” says Sidney Milkis, a political scientist and Miller Center fellow at the University of Virginia. “We’ve become a presidency-obsessed democracy.” A key question, Milkis says, is “whether 300 million people can expect so much from one individual and still consider themselves involved in something that can be described as self-government.”

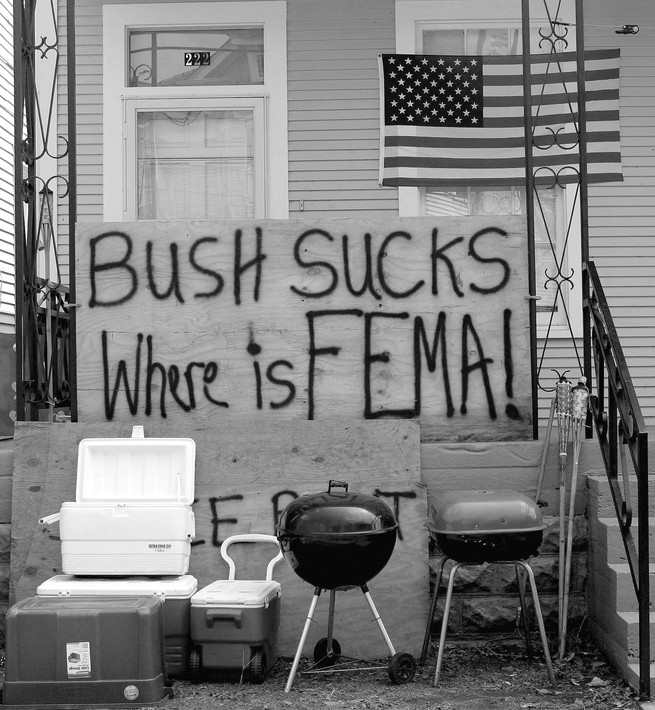

Disaster response is by now such a prerequisite that if a president doesn’t act—and isn’t seen acting—it can wreck his presidency. “It used to be that presidents were advised to let the fema director and governor handle disaster response,” says Andy Card, who managed the Hurricane Andrew response for George H. W. Bush, in August 1992, and served as George W. Bush’s chief of staff during Hurricane Katrina, in 2005. “Now the expectation is that if a president is not talking about it all the time, he is asleep at the switch, or Marie Antoinette.”

George W. Bush’s presidency never really recovered from the photograph of him looking down from Air Force One on the vast area harmed by Hurricane Katrina. In 2010, when an explosion at the Deepwater Horizon offshore-drilling platform led to 87 days of oil belching into the Gulf of Mexico, critics labeled it “Obama’s Katrina.” The typical critique was summed up by the headline on a Peggy Noonan column in The Wall Street Journal: “He Was Supposed to Be Competent.”

Eisenhower-esque detachment was no longer viable. Amid crashing favorability ratings, Obama interrupted his own vacation to tour abandoned, oil-slicked beaches. “I ultimately take responsibility for solving this crisis,” he said. “I am the president, and the buck stops with me.”

That phrase—a succinct expression of presidential obligations—is like the presidency itself: It has spilled out of its original container. When Harry Truman placed a sign on his desk reading the buck stops here, it meant that some decisions, only the president can make. It did not mean that the president is responsible—and therefore to blame—for everything that happens in the executive branch, much less the nation.

Lyndon Johnson made the most of the new, televised presidency, but the co-dependency with the cameras started with his predecessor, John F. Kennedy. In 1960, Kennedy, a young senator and candidate for president, filmed television ads that showed him shaking hands with miners in West Virginia before they dropped down 500 feet to start their eight-hour shift. Kennedy wasn’t just cutting a dashing figure to be beamed into living rooms; he was making an argument about presidential campaigns. “I believe that any Democratic aspirant to this important nomination should be willing to submit to the voters his views, record, and competence in a series of primary contests,” Kennedy had said when he’d announced his campaign. Only after such a primary contest, he’d argued, could the candidate understand the concerns of the people, and prove his readiness to act on them. An ad the campaign took out in a West Virginia newspaper made Kennedy’s proposition clear: Votes for his opponent, Hubert Humphrey, were shown landing in a garbage can. Votes for Kennedy were shown dropping from the ballot box through the roof of the White House.

Kennedy’s view that candidates should make their case directly to the people may hardly seem controversial by contemporary standards, but it was part of a radical change in the path to the presidency. In designing the office, the Founders worried that the executive would be whipsawed by the passions of the people rather than driven by reason and good character. Because of this fear, the Founders did not want candidates to campaign for the office, believing that stumping for votes would warp their priorities. The electoral process might elevate men who had simply played to the crowd; once in office, such a president might pander to the people rather than instituting sound policy. Without a constant need to court voters, the Founders reasoned, presidents could calmly pursue the best interests of the country.

For a century, the system worked as intended. Candidates “stood” for election, but did not deign to stump for votes at rallies. Men such as Andrew Jackson argued for a closer connection between the people and the president, but the taboo against campaigning was durable. The parties still picked their presidential candidate in the smoke-filled rooms of legend. In the early 20th century, reformers such as Woodrow Wilson asserted that the modern age required presidents to be more responsive to the voters. A president shaped by an election system with voters at the center would not abandon them once in office and would know how to summon what Wilson called “the common meaning of the common voice.”

Kennedy’s successful use of the previously obscure primary system helped to make state-by-state barnstorming the established road to a party nomination and eventually the White House. And just as the Founders had surmised, prolonged exposure to the people had a powerful effect. Kennedy’s first executive order increased the amount of food distributed to needy Americans in economically distressed areas, a direct result of his time spent in West Virginia. The votes had gone right to the White House.

Looking out for the interests of the poor may sound like an unalloyed good. But party reforms in the last quarter of the 20th century pushed the nominating process further toward the direct election of delegates. This encouraged candidates to make ever more lavish promises and to tout their singular power to deliver on them. “Longer and longer campaigns have contributed to a prolonged bidding war of candidates making more and more promises as to what government will do if they are elected,” says Roger Porter, who served in the Reagan and Ford administrations and now teaches at Harvard’s Kennedy School.

Primaries encourage candidates to do whatever keeps the crowd in a roar, as Howard Dean explained when looking back on his infamous “scream” after the 2004 Iowa caucuses. “I’d get out there and I would talk about policy and there was no adrenaline rush,” he told FiveThirtyEight. “People kind of went ‘uh-huh, uh-huh,’ and I really wanted that huge charge of being able to crank them all up and to believe in themselves again and get enthusiastic, and I would succumb to that.” Trump took this trend to its logical conclusion, promising voters every beneficial outcome and proclaiming at his convention about the problems that America faced: “I alone can fix it.”

The present system elevates the crowd-pleasing qualifications above all others, and sets expectations for what a president can do well beyond what is actually possible in office. Media coverage, meanwhile, keeps the show going—and keeps the focus on the show. Cable networks promote debates with zooming lights and “voice of God” announcers, as if the candidates are backstage getting their hands wrapped in tape and loosening up with the medicine ball. Debate coverage is mostly like a theater review, and it starts before the curtain has come down. As Peter Hamby, a former CNN reporter and the current head of news at Snapchat, demonstrated in a 2013 paper for Harvard’s Shorenstein Center, in the age of social media, voter impressions during debates are formed in the first minutes.

Candidates play to the snap judgments, practicing set-piece outbursts. In 2012, when Obama was perceived to have lost the first debate, his team emphasized that he needed to be a better performer. He was to be “fast and hammy.” When he would give a long and dry answer in practice sessions, he would be reminded: Fast and hammy!

As campaigning has become more about performance, the skills required to be president have become more defined by talent on the stump, an almost perfect reversal of what the Founders intended. The current system is so focused on persuasion over policy, argues Jeffrey K. Tulis, the author of The Rhetorical Presidency, that he sees the country as governed by a second Constitution, one that is in tension with the original. The second Constitution puts a premium on active and continuous presidential courtship of popular opinion, on hot action over cool deliberation. “How could a president not be an actor?,” Ronald Reagan asked. Or, failing that, a reality-TV star?

Wilson wanted candidates to be in touch with the public, but he viewed campaigning as “a great interruption to the rational consideration of public questions.” We are now in an age of permanent campaigning, in which rhetorical talent is seen as a proxy for governing ability. In 1992, after Bill Clinton beat George H. W. Bush, Vice President Dan Quayle said, “If he governs as well as he campaigned, the country will be all right.” Republicans had argued that Clinton’s character faults disqualified him from office. In defeat, Quayle was articulating the common modern view—ratified by voters—that being a gifted campaigner was the more important quality.

With the line between campaigning and governing blurred, newly elected presidents are overconfident in their ability to tackle the job. Richard Neustadt, the historian of the presidency, described the mind-set of the winning campaign team:

Everywhere there is a sense of page turning, a new chapter in the country’s history, a new chance too. And with it, irresistibly, there comes the sense, “they” couldn’t, wouldn’t, didn’t, but “we” will. We just have done the hardest thing there is to do in politics. Governing has got to be a pleasure by comparison: We won, so we can!

Modern presidents who have just come to office on the strength of their rhetoric and showmanship are encouraged to continue relying on those skills. “They have been talking for two years, and that’s nearly all they’ve been doing. When they win, they conclude that they can convince people of anything,” the Texas A&M political scientist George C. Edwards III says. “The feedback is pretty strong.”

Governing is about more than talking, though. “The first thing a president needs to understand,” says Max Stier, the CEO of the Partnership for Public Service, “is that in order to run a government, they are going to need capabilities different than the ones needed to win the right to run the government.”

Selling the voters on the idea that you are better than your opponent requires a different set of skills than achieving your preferred outcome on health-care legislation, where there is not one alternative but a series of alternatives on a series of aspects of the policy. Campaigning requires attack and comparison. Governing requires deliberation, cooperation, negotiation. A candidate for president has one constituency: the voters. A president has to navigate the interests of many parties: the voters, Congress, foreign leaders. The attributes that got him into office—Kennedy’s youthful vigor, Reagan’s nostalgic vision, Trump’s bombast—are only somewhat helpful in a job that requires a host of other skills.

In an ideal system, incoming presidents would have months of orientation to learn the ropes and break their rhetorical addiction. No such school exists for presidents. There is a transition process, but it doesn’t sufficiently prepare a president or his team.

Presidential transitions are a bigger undertaking than any private-sector transfer of power. In business, large mergers and acquisitions typically take a year or more and involve hundreds of staffers. Dow Chemical and DuPont announced their $130 billion merger in December 2015, and it closed in September 2017. A president-elect and his team have two and a half months between victory and inauguration to figure out how to run a $4 trillion government with a civilian workforce of 2 million, to say nothing of the military. The United States federal government is the most complicated conglomerate on the planet.

Unlike in a business acquisition, in which a new leader might retain staff from the target company as well as bring in his own trusted people, a president must start almost from scratch. He has as many as 4,000 fresh political appointments to make, including for more than 1,000 top leaders who will require Senate confirmation.

Putting a team in place quickly is crucial to making good decisions. Some temporary holdovers can manage in the interim, but they can get you only so far. “You’re not perceived as having authority; you’re like the substitute teacher,” Max Stier says of the holdovers. “And it’s hard to coordinate without having the authority and time to build relations.” With so many jobs to fill, few teams get much of a chance to work together before natural attrition starts.

The rush to staff up encourages new presidents to fill the administration with the people who helped them win the office in the first place, further entrenching a campaign mentality within the White House. The presidential scholar Shirley Anne Warshaw, who teaches at Gettysburg College, found that 58 percent of the senior posts in the Obama administration were filled by campaign staff. Some may have been suited to the unique challenges of the executive branch, but the system does not allow enough time to make certain of it. New presidents just have to hope for the best.

Presidents thus enter office burdened with campaign instincts, not governing ones; with a team that may lack experience in the tasks at hand; and with a long list of promises to keep to voters. In such a situation, patience would seem to be called for. That was Eisenhower’s advice: “You do not lead by hitting people over the head. Any damn fool can do that, but it’s usually called ‘assault,’ not ‘leadership.’ I’ll tell you what leadership is. It’s persuasion, and conciliation, and education, and patience. It’s long, slow, tough work. That’s the only kind of leadership I know, or believe in, or will practice.”

Except, as Lyndon Johnson warned, new presidents only have a year before Congress starts thinking about midterms, which makes bold or bipartisan action difficult. David Broder of The Washington Post characterized Johnson’s first-100-day freneticism as a “half-mad, half-drunk Texas square dance, with Johnson, the fiddler and caller, steadily increasing the tempo, speeding up the beat.” That was before the era of hyperpartisanship, which has made presidential honeymoons short or nonexistent. No president wants to boast at his day-100 interview, “We’ve really made some strides in mastering organizational capacity and creating flow in our lines of authority.”

The push to meet expectations set during the campaign encourages frantic behavior. Harried aides cook up executive orders—even if the president campaigned against them and even if they don’t actually do much. Trump’s early days were a flurry of such actions. The cameras were called in and the theme music was cued, but several of his executive actions merely instructed agencies to look at problems and issue reports. I alone can PowerPoint it! Others, such as the travel ban, the exclusion of transgender people from the military, and tariffs on steel and aluminum, were poorly vetted and incited massive backlashes.

We all know what this desire to execute looks like in our own lives. The president is the jumpy man who presses the elevator button a second time, then a third time—with his umbrella. It feels good. It looks like action. But the elevator does not move faster.

III. An Unfathomable Psychological Squeeze

The former White House photographer Pete Souza’s book, a collection of more than 300 photos of Barack Obama’s presidency, is a tour through the psychological landscape of the office. President Obama stands by the bedside of wounded soldiers he sent into battle and in the ruins left by natural disasters. He counsels his daughter from a seat on the backyard swing while on television oil oozes from the Deepwater Horizon spill. He sits, leans, and paces through endless meetings. He plays host—to the Chinese president, the Israeli premier, Bruce Springsteen, Bono, kids in Halloween costumes, African American boys and girls.

The presidential brain must handle a wider variety of acute experiences than perhaps any other brain on the planet. Meanwhile, the president lives in a most peculiar unreality. His picture is on almost every wall of his workplace. The other walls contain paintings of the men who achieved greatness in his job, as well as those who muddled through. It’s like taking a test with your competition’s scores posted around you.

When a president travels, he has his own doctor, security, exercise equipment, and water. It all gets moved around on his airplanes. If the Secret Service thinks the bathroom in a foreign country might cause the president to slip, agents will lay down protective strips to give him traction when he gets out of the tub. Grover Cleveland used to answer his own front door. Now presidents touch door handles only in their private quarters. Their lives are babyproofed.

At the same time, the American president is constantly subjected to the harshest scrutiny from outside his bubble. This is a long-standing tradition. The New York Times devoted 500 words to Calvin Coolidge’s indigestion. (It was the cantaloupe.) The president is the biggest celebrity in the world. Eyes are always watching, ready to imbue a grimace with meaning.

Everyone waves—and everyone expects a wave in return. If the president is close enough, people expect a selfie. Photographers can capture a note about needing a bathroom break that he jots in a meeting, and someone is always at a keyboard ready to make a cultural moment out of a thought that escapes his subconscious. Obama told an aide that he had a recurring dream. In it, he was enjoying a peaceful walk. He was alone and undisturbed. Suddenly, he was noticed. The dream became a nightmare, and he awoke.

While emoting at all the appropriate times in all the appropriate ways, a president must also wear masks to hide his intentions—from world leaders, political adversaries, and allies alike. This allows him room to negotiate. Senator Huey Long complained about Franklin Roosevelt: “When I talk to him, he says, ‘Fine! Fine! Fine!’ But [Senator] Joe Robinson goes to see him the next day and he says, ‘Fine! Fine! Fine!’ Maybe he says, ‘Fine!’ to everybody.” New York Governor Al Smith was once asked whether he had gotten a commitment from Roosevelt, and responded, “Did you ever nail a custard pie to a wall?” Roosevelt’s flexibility was considered a great and necessary presidential skill. But a man who wears masks must do a lot of work to keep them from slipping.

Can one person handle all this? In 1955, former President Herbert Hoover completed a review—his second—of executive-branch efficiency and suggested the addition of an administrative vice president to help the overloaded president. (The existing vice president was apparently already too busy.) Hoover’s report was issued a few months before President Eisenhower had his first heart attack. It was the fifth heart attack or stroke to hit a current or former president since the Wilson administration ended, in 1921. This caused the columnist Walter Lippmann to wonder whether the job was too much for one man to bear. Addressing the “intolerable strain” on the president, Lippmann wrote, “The load has become so enormously greater … because of the wars of this century, because of the huge growth of the American population, of the American economy, and of American responsibilities.”

Since then, the weight of the job has grown even heavier. The Souza photograph that marks the day Obama describes as the hardest of his presidency shows him standing with one of the 26 families he comforted after the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary. That day, when a mother broke down, the president handed her a tissue.

Presidents aren’t trained as pastors, but they have been thrust into that role, too. They must comfort the nation in the shadow of tragedy. Woe unto the president who selects the wrong sermon for the occasion. “Now it’s not enough to do it,” Mitch Daniels, the former Indiana governor and top assistant to Reagan, says of performing the pastor role. “You have to do it in the exactly right, sensitive way.” And the better you do it—the more aware you are that a woman beside you needs a Kleenex—the more draining it is on your soul.

Then there are the men and women who might die as a result of the president’s orders. He may soon be called on to console their families, too. An aide to George W. Bush says that when the president was deciding whether to send more troops into Iraq in 2007, at a time when the public and members of his own administration wanted the U.S. to withdraw, he began wearing a mouth guard at night, because he was grinding his teeth so much in his sleep.

Truman said the decision to go to war in Korea had been the hardest decision of his presidency. A letter sent to him by the father of a soldier who died in that war, returning his son’s Purple Heart, suggests just how hard it was:

Mr. Truman,

As you have been directly responsible for the loss of our son’s life in Korea, you might as well keep this emblem on display in your trophy room, as a memory of one of your historic deeds.

Our major regret at this time is that your daughter was not there to receive the same treatment as our son received in Korea.

Truman kept the letter in his desk drawer long after his term ended, a testament to the weight that remained on him even after he left the Oval Office. If a president thinks too much about the widows he’s making or the children who will never know their mother because of his orders, he might not be able to perform the role of commander in chief. Learning to compartmentalize is a necessity for presidents. Some compartments are locked so tight, even the president’s closest advisers never see their contents.

During the final phase of planning the operation to kill Osama bin Laden in the spring of 2011, Obama chaired the National Security Council on five occasions. Those five days tell the story of just how quickly a president must switch between his public and private duties. The events that took place immediately before and after those secret bin Laden meetings included: an education-policy speech; meetings with leaders from Denmark, Brazil, and Panama; meetings to avoid a government shutdown; a fund-raising dinner; a budget speech; a prayer breakfast; immigration-reform meetings; the announcement of a new national-security team; planning for his reelection campaign; and a military intervention in Libya. On April 27, the day before Obama chaired his last National Security Council meeting on the bin Laden raid, his White House released his long-form birth certificate to answer persistent questions about his birthplace raised by the man who would be his successor.

In the two days before the raid itself, Obama flew to Alabama to visit tornado victims and to Florida to visit with Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, who was recuperating from a gunshot wound. On Saturday, April 30, with the operation under way but its outcome uncertain, he attended the White House Correspondents’ dinner, where he had to entertain journalists with a comedy routine. In the joke-writing process, he had removed a quip about bin Laden. His aides were given no hint of why.

The high-stakes military operation made this stretch particularly fraught psychologically, but it wasn’t entirely out of the ordinary. Denis McDonough, who served Obama as chief of staff, says the pace was usually such that it became “a rare ability to know what day it was. Every night feels like Tuesday night.”

The relentlessness of the job depletes a president’s powers of restraint, and yet restraint is crucial for wise decision making. “You have to have a high tolerance for pain,” says Jay Carney, one of Obama’s press secretaries. “Sometimes that means letting yourself be misunderstood,” refusing opportunities to score easy debating points in favor of the long view.

At times, an opportunity to get a quick win has to be put off for a later, bigger victory. Focusing on short-term success might please the pundits, but it keeps an administration from doing the hard, obscure, boring work needed to address looming national problems that will be too big to tackle once they become emergencies—the shrinking middle class, the changing climate, the rising health-care costs straining the federal budget. Even the most above-it-all president is continuously tempted to privilege the small over the big and the now over the future.

The current president gives in to such temptations. It may be an efficiency—what a relief to give vent to your every moment of pique. But Trump is serving with historically low approval ratings, and even his supporters do not like his constant sniping and complaining about the merest slight. The risk of impulsiveness isn’t just to the president’s own reputation. It also tarnishes the prestige of the office when a president fumes over the latest segment from Fox & Friends.

Successful presidents learn to keep their powder dry, even when doing so might make them seem weak. A president has the power to determine who lives and who dies—sometimes by the thousands—yet he is also frequently powerless, which led the political theorist Hannah Arendt to define the president of the United States as at once the strongest and the weakest of all national leaders. A president must be willing to endure that paradox. As Lyndon Johnson put it, sometimes the president is little more than “a jackass in a hailstorm.”

IV. A Historic Partisan Gap

“Any discussion of how hard it is to manage the presidency has to start with the weakness of Congress,” Denis McDonough says. “You can’t have a president solve problems the legislative branch has not.”

On September 30, 1990, President George H. W. Bush stood in the White House Rose Garden before a bank of Brooks Brothers suits containing the leaders of Congress. The government was set to run out of money that day, a familiar story to contemporary ears. But what those men said would seem less familiar. The Republican president praised the Democratic leaders, and they praised him right back. Congressional leaders of both parties praised each other.

The president and assembled lawmakers were announcing the Budget Summit Agreement, a mix of spending reductions and tax increases meant to tame deficits. The agreement capped five months of intense wrangling, which had ended in a sprint of negotiations. For 11 days and nights at Andrews Air Force Base, meat-fed men (Monday was prime-rib night) had argued until they’d come to an accommodation. The outcome was one the Framers would have approved of: Lawmakers of strong opinions had compromised rather than resorting to open conflict. The results were imperfect, but preferable to inaction.

At least, that was one way to see it. The alternative view was that leaders of both parties had compromised their principles, and no one had done so more than Bush himself, having gone back on the “no new taxes” pledge he’d made during the 1988 campaign. This sentiment played out on the other half of CNN’s split-screen coverage that overcast day. Juxtaposed with Bush was footage of Representative Newt Gingrich leaving the White House. The second-ranking House Republican refused to join the celebration, or to follow his party’s president. “It was a betrayal of his pledge and a betrayal of Reaganism,” Gingrich told the Bush biographer Jon Meacham. Gingrich headed back to the Hill, where conservatives waited to greet him as a rebel hero.

Bush’s victory that day sowed the seeds of his defeat in the 1992 election. “It did destroy me,” Bush told Meacham. After this, it was taken as truth that no Republican politician could survive disappointing the conservative core.

The split screen that day encapsulated the dilemma for modern presidents: Work with the other side and be called a traitor, or refuse to work with them and get nothing done. Days after the Rose Garden ceremony, the deal announced there collapsed. Liberal Democrats voted against their leaders because they wanted more government spending. Conservative Republicans voted against their leaders because they opposed tax increases and wanted more spending cuts. Republicans running for reelection in 1990 needed the base to win. If they’d rallied behind the budget deal, they’d have risked being voted out of office. “What is good for the president may well be good for the country, but it is not necessarily good for congressional Republicans,” Representative Vin Weber of Minnesota, a Gingrich ally, told The Washington Post. “We need wedge issues to beat incumbent Democrats.”

In the 27 years since the announcement of the doomed Budget Summit Agreement, the parties have become only more partisan. Particularly in the Republican Party, primary challenges await lawmakers who dare enter into a bipartisan compromise. The purity ministry is proctored by talk-radio hosts, well-funded outside organizations, and countless social-media warriors.

The growth in partisanship means that when it comes to the basic business of government, the president and Congress are in constant turmoil. Shutdowns and federal-budget stalemates are now regular occurrences. Congress has not passed a spending bill on time in 20 years. Congressional oversight, once used to identify future risks and monitor the executive branch, is now robust mainly when it comes to tying the opposition’s shoelaces together.

When presidents do work with Congress, the achievements are partisan. Obama signed health-care reform flanked only by Democrats. Trump celebrated his tax-cut bill with only Republicans.

Bipartisan ceremonies at the White House have become rarer, low-stakes affairs, or the last of a kind. One of the final times Republicans showed up at the Obama White House was to promote free trade, an issue Trump used to defeat his GOP rivals. Republicans are no longer such boosters of the idea. “The political system acts against success for a president,” says Mitch Daniels, who also served as the director of the Office of Management and Budget under George W. Bush. “The new tribalism is right up there with the national debt as the biggest threat to our nation.” Secretary of Defense James Mattis agrees: The greatest threat America faces, he told me, is “the lack of political unity.”

When the relationship between Congress and the White House breaks down, pundits like to invoke Lyndon Johnson. Through sheer force of will, they suggest, a president can get the machine going again, spurring Congress into action.

But Johnson is not the model. He had a unique résumé as a former Senate majority and minority leader and could take advantage of a martyred president’s legacy to build support for his policies. His party also had a large majority in both houses.

The idea that presidents can break through gridlock if they just try hard enough nevertheless persists. “The president has got to start inviting people over for dinner,” Michael Bloomberg, the former mayor of New York City, advised during Obama’s tenure. “He’s got to play golf with them. He has to pick up the phone and call and say, ‘I know we disagree on this, but I just want to say—I heard it was your wife’s birthday’ or ‘Your kid just got into college.’ He has to go build friendships.”

Presidential candidates buy into the Johnson myth because it allows them to pitch themselves as the unique solution to Washington’s problems. “One of the things I’m good at is getting people in a room with a bunch of different ideas, who sometimes violently disagree with each other, and finding common ground and a sense of common direction,” Obama told Steve Kroft on 60 Minutes in 2008.

By the end of Obama’s first term, the president and his aides had given up on the idea of deal making entirely. Pundits regularly advised him to just sit down and have a drink with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, the way Truman shared bourbons with congressional leaders. “You have a drink with Mitch McConnell,” Obama joked in response. Two years into Obama’s tenure, McConnell had said the GOP’s most important job was making sure the president served a single term. Privately, little irked Obama more than the claim that he should be doing more to work with an opposition that didn’t want to work with him.

The call for presidents to sit down with the leaders of the opposing party is a vestige of a time when presidents and lawmakers were less connected to their party and when the parties were more ideologically and geographically heterogenous than they are today. They could appeal to ad hoc coalitions in Congress, which formed around beliefs on specific issues. As Senate minority leader, Johnson, a Democrat, helped Eisenhower defeat conservative Republicans who were pushing the Bricker Amendment, which would have limited presidential power in foreign affairs. As president, Johnson relied on the Republican Everett Dirksen to get civil-rights legislation passed over the opposition of conservative Democrats. As late as 1978, Republican Senate Minority Leader Howard Baker was willing to risk his own presidential aspirations to help Democratic President Jimmy Carter get the 67 votes needed to give Panama control of the Panama Canal.

The electoral map once encouraged compromise and cross-party coalitions. During Nixon’s and Reagan’s terms, more than half of the senators in the states they carried were Democrats. Those senators had constituents who liked the president, even though he belonged to the other party, which gave those senators room to make deals with him. About 80 percent of the senators from the states Obama won were of his party. The same is true of Trump.

These lawmakers have to answer to voters who are as far apart on the political spectrum as they’ve been in generations. The Pew Research Center has been studying partisan positions since 1994, testing views on fundamental political issues—whether regulations do more harm than good, whether black Americans face systemic racism, whether immigrants are a burden, and whether corporations make reasonable profits. In 1994, the members of the two major parties were only 15 percentage points apart, on average. Now they are an average of 36 points apart. That partisan gap is much larger than the differences between the opinions of men and women, of black and white Americans, and of other divisions in society. A president can’t build a coalition to support health-care legislation when the two parties fundamentally disagree whether the government should be involved in health care at all.

The partisan gap in how people view presidents is also as wide as it has ever been. On average, during his two terms Eisenhower enjoyed the approval of 49 percent of Democrats. Obama had the support of 14 percent of Republicans over the course of his presidency. Just 8 percent of Democrats approved of Trump last summer. In this environment, no matter how many drinks a president has with the leaders of the opposition, he’s not going to change their minds. “I don’t understand how you manage people in Congress in either party into seeing that some level of accommodation is in their interest,” says Bolten, the former George W. Bush chief of staff. “Presidents can’t negotiate like Lyndon Johnson, because members have no reason to fear the president.” But voters don’t want excuses. They want action. When Congress can’t act, it puts more items on the president’s to-do list, though he frequently lacks the tools and authority to act himself.

V. How to Fix It

To repair the modern presidency, politicians, the public, and the press need to change their expectations about the office and focus on what is realistic. The president is not a superhero. He is human, fallible, capable of only so much. So what do we want him to do—and how can we help him do it?

hit the ground running

“The Romney Readiness Project” is the most valuable contribution to the modern presidency from a man who didn’t win the office. It is a 140-page distillation of the work of Mitt Romney’s transition team, a six-month process of preparing for the job in 2012. The volume is filled with organizational charts, prioritization matrices, and tables that match jobs with responsibilities. Six hundred people were involved in planning for a Romney transition by the end of his campaign, participating in exercises in which they practiced moving ideas and legislation through the federal system. When people talk about the benefits of having a businessman in the White House, this example of careful attention is no doubt what they expect.

The businessman who succeeded where the former Massachusetts governor failed did not exactly bring the same rigor to the transition process. Donald Trump’s team followed a playbook that seemed at times to have been drawn on a napkin. The transition experienced all the typical flaws—infighting, skepticism toward those with expertise from the previous administration, wasted work—and a few new ones for good measure. Veterans of previous White Houses stressed to Trump’s team the value of building systems to manage information and aid decision making. They report that they were either humored or ignored by frantic staffers trying to keep up with the boss’s demands.

Max Stier of the Partnership for Public Service has devoted his career to trying to make the federal government operate more efficiently. He pushed Congress to pass the Pre-Election Presidential Transition Act, which put some structure in place to help a new president prepare. And he suggests that Congress should seek to formalize a transition process like the one Romney intended to follow.

Under Stier’s new plan, each party’s nominee would take steps to form a government-in-waiting and learn the folkways of the federal system. “It’s not fair to the American public,” he says, “for a candidate to say, ‘You know what, I’m going to go through that Now what? moment when I get into office, and you’re all just going to suffer along with me on that.’ ”

Voters and the media could do their part by dispensing with the idea that any candidate who thinks about the nuts and bolts of the presidency before the first Tuesday in November is prematurely measuring the Oval Office drapes. We should do the opposite: evaluate candidates based on their commitment to the transition, using it as a sign of seriousness. How they think about the transition offers a view into how they would approach the job: Can they focus on an important long-term task while engaged in the day-to-day urgency of the campaign? Can they put the right people in place?

Since the 2016 election, public attention has understandably focused on fake news, Russian interference, and how to keep elections from being destabilized again. But susceptibility to foreign manipulation is hardly the only flaw in our electoral system. The American public and press also need to reconcile the gap between the office as it is debated during campaigns and its actual demands. We need to do a better job of using the campaign to test for the qualities that will serve a president in office: management talent, governing effectiveness, and temperament. In a job with such psychological strain, we should pay closer attention to the candidates’ disposition and mettle. “One thing about the presidency is that it doesn’t build character; it reveals it,” says Dan Bartlett, the George W. Bush communications director.

Let’s not kid ourselves, though. This kind of shift in public attitude would be miraculous given today’s tribalism, the dominance of hot-take journalism, and the churn of social media. Reporters and pundits gravitate toward easy narratives, and candidates, parties, special-interest groups, and financial kingmakers all benefit from crude, predictable fights over values and identity. When so much advantage can be gained by stoking emotions, why stop and consider a candidate’s reason?

Joseph Califano, Lyndon Johnson’s former domestic-policy aide, suggests that one possible way to interrupt the present system is for centrists to storm the primaries. A small percentage of party members currently take part in the presidential nominating process. Most of those who do are ideologically extreme, more interested in litmus tests than testing for experience and character. If people with fewer fixed opinions joined in, they might select candidates who demonstrate the preparedness and open-mindedness to govern.

Elevate Experience

While we’re in the realm of the unlikely, we should also stop thinking of experience in Washington as a liability. This is not a new tension in American politics. Hoover noted, “When we are sick, we want an uncommon doctor; when we have a construction job to do, we want an uncommon engineer; and when we are at war, we want an uncommon general. It is only when we get into politics that we are satisfied with the common man.”

Today, candidates who have no familiarity with Washington enjoy a distinct advantage; those who do are seen as denizens of the swamp. This bias ensures that the president has none of the skills and relationships honed by years of service that might give him a fighting chance of breaking through the partisan gridlock.

Voters—particularly Republican ones—have a tendency to romanticize the can-do spirit of the corporate CEO. But we don’t engage in anything like the CEO selection process when we hire our commander in chief. Gautam Mukunda, a Harvard political scientist and professor of organizational behavior, has studied how the electorate might better seek out the qualities of command in presidential candidates. He points out that businesses rely on a filtering system that tries to let through only those leadership candidates who have the basic attributes necessary for the job. “We shouldn’t believe that a good CEO [necessarily] makes a good president,” Mukunda says, “but we should notice that CEOs are selected through a process that is far more careful and deliberate and rationally destined to pick candidates who fit the job.” Americans who pledge a fondness for the effectiveness of the business world could apply some business-world wisdom to their own decision making by picking leaders the way companies do: by favoring, not punishing, candidates with pertinent experience.

OnBoard the President

A manual for newly elected presidents might include the following tips:

Previous success does not predict future success. In fact, previous achievements may impede progress as president. “The natural instinct of a newly elected president is to approach the job like they operated in their previous roles,” says Mike Leavitt, the former Utah governor and chairman of Romney’s transition team. But the presidency is unlike any previous job. The sooner presidents realize that they are going to have to master new skills to run an effective White House, the better. Every president has to learn this, Leavitt says. “They know how to get elected, but they have to learn how to govern.”

Actions speak louder than words—or at least they’re more important. Because rhetoric has been the coin of the realm during the campaign, new presidents fall into the trap of thinking they can talk their way around any problem. “The modern presidency is not impossible,” the political scientist Elaine Kamarck writes in her book Why Presidents Fail. “But it does require a reorientation of the presidency itself—toward the complex and boring business of government and away from the preoccupation with communicating.”

If you want to move fast, you first need to move slow. This is especially hard medicine to take, because presidents are so flushed with new power. On Christmas morning, no one wants to wait for Mom and Dad to get up to open presents. Most new presidents campaigned on the idea that they would not fall prey to the incumbent’s sluggishness and lack of will. Things will be different when I get to town, they told their adoring crowds. But there are no easy calls as president. The system for presidential decision making has to be methodical, because presidential decisions are uniquely difficult. “Nothing comes to my desk that is perfectly solvable,” Obama told Michael Lewis, writing for Vanity Fair. “Otherwise, someone else would have solved it. So you wind up dealing with probabilities. Any given decision you make you’ll wind up with a 30 to 40 percent chance that it isn’t going to work. You have to own that and feel comfortable with the way you made the decision. You can’t be paralyzed by the fact that it might not work out.”

In many instances, a president makes a decision without the certainty that comes from having done all the work leading up to it. “What presidents do every day is make decisions that are mostly thrust upon them, the deadlines all too often outside of their control on options mostly framed by others,” Richard Neustadt, whose memos on the presidency have guided generations in the office, wrote. To make these decisions a president needs to have space for reflection. “We used to put time on his schedule just so that he could think,” Leon Panetta told me, referring to Bill Clinton.

Embrace the bubble. Obama eventually came to realize that he had to consider the “Barack Obama” discussed in the press to be an entirely different person from himself to keep from becoming personally invested in criticism. Presidents have to ignore the reviews and the constant chatter; there is too much of it, and too much of it is uninformed. If he can’t ignore the chatter, he needs to find a safe way to vent: When criticism got to him, Harry Truman would write “long hand spasms,” splenetic outbursts that his staff were empowered to dispose of properly. To guard against being out of touch, meanwhile, a president has to designate someone to tell him the truth and then believe that person when he delivers unwelcome news. Candor will be elusive in the Oval Office, where everyone’s instinct is to flatter the boss. “The subordinate needs to be willing to tell the truth to power,” former Defense Secretary Robert Gates told me on Face the Nation last May, “but the boss needs to be big enough to recognize that person is actually trying to help them.”

Trust your staff. Given the weight of every decision, and the fact that even good presidents can make bad ones, the system that delivers a set of options to the Resolute Desk has to be as solid as possible. Alternatives have to be presented by staffers who have expertise, understand the president’s mind, and can trust that their work will be put before the president fairly. “The first thing I think the American people should be looking for is somebody that can build a team and create a culture that knows how to organize and move the ball down the field,” Obama told me before the 2016 election. “No matter how good you are as president, you are overseeing … the largest organization on Earth. And you can’t do it all by yourself.”

Obama’s prescription is similar to the road map drawn by H. R. Haldeman, Nixon’s chief of staff for much of his administration, who created the template for the modern White House organization. Using his experience as an advertising executive, he drew up a careful system to staff the presidency. “Nothing goes to the president that is not completely staffed out first for accuracy and form, for lateral coordination, checked for related material, reviewed by competent staff concerned with that area, and all that is essential for Presidential attention,” he wrote.

What Haldeman knew is that an office this complex can’t have improvisational staffers—or an improvisational president. (An ironic bit of wisdom, given his fate and that of the Nixon administration, but no less valid for that ignominy.) A president can of course overrule his staff, or change his mind. But there needs to be a process, and a baseline of consistency. “Unpredictability can be occasionally helpful,” says Kenneth Duberstein, who served as White House chief of staff for Reagan. “But it can’t be an operating management style.”

“It’s like an air-traffic-control tower managing 100 airplanes who think they have an emergency and need to land, now,” says Leavitt, who also served as secretary of health and human services under George W. Bush. “To work well, the presidency has to have order and structure. To someone supremely confident in their ability to instinctively know the answer to every question, this could seem overly bureaucratic. However, when the process is not allowed to operate, the consequence is a lot of crashes.”

The crashes may not come immediately, but they are inevitable, and when they happen, a system for effective operation cannot be put in place retroactively. This is perhaps the greatest looming challenge for the Trump administration, which is stress-testing everything we know about the orderly operation of a White House. “Effective government is like an airbag,” says Harvard’s Mukunda. “You don’t notice it most of the time, but when things go wrong, you really want it to be there.”

Empower your Cabinet. Even if his White House operation is zooming safely down the interstate, a president can’t make every decision from the Oval Office. There’s just too much to do. Instead, presidents should follow Calvin Coolidge’s model. “Perhaps one of the most important accomplishments of my administration has been minding my own business,” he said.

In the modern executive branch, that means giving Cabinet secretaries some leash. George Shultz advised Donald Trump to resist letting the White House dominate everything. “That has become a tendency, to put decision making and even operational things in the White House,” says the former secretary of state under Reagan and Treasury secretary under Nixon. “So I would hope the president might say something like this: ‘I consider my Cabinet and sub-Cabinet people to be my staff. Those are the people I’m going to work with to develop policy. And they are the ones who are going to execute it under my supervision. But they’re going to execute it.’ When you do that, you get good people, you get all people who have been confirmed by the Senate, and you get better policy and you get better execution.”

To allow this kind of delegation to take place, though, Americans will have to give up their conception of where the buck stops. If a Cabinet officer makes a bad decision, the president should fix it and the system should adapt. But a president should not be held responsible for every decision made in every corner of his administration, or he’s liable to do as Carter did and try to make every decision himself—an impossible task. The media, for their part, will have to cover Cabinet officials in a substantive way and not just as a source of palace intrigue. There are better uses of shoe leather than sussing out where, exactly, Rex Tillerson was sitting when he learned he’d been fired.

Radically Simplify the Office

Delegation alone won’t be enough, though. Mitch Daniels argues that the overload of the job can be solved only by radically paring it back. This might require a break between the functional role of the job (defending the nation and building consensus for important legislation, the places where the presidential brain and only the presidential brain can be applied) and the ceremonial part of the job (visiting disaster sites, welcoming NCAA champions). The latter category might be impossible to lose altogether, but could probably be outsourced to the vice president. A future president might also redefine the role of the first spouse, tasking her—or him—with more of the visiting and hosting. In his 2017 book, The Impossible Presidency, the University of Texas historian Jeremi Suri goes so far as to suggest adding a European-style prime minister who could take work off the president’s desk. “The next successful president is likely to be somebody who concentrates relentlessly on a few well-chosen goals,” Daniels says. “Someone who makes it plain that ‘there is only so much of me and there are only so many days. We have big problems. It’s not that I don’t care. I care deeply, but you’re not going to see me doing these things. You hired me to do a different job.’ ”

It’s hard to imagine an American president speaking that starkly to the American people. Then again, this may be another way in which Trump, however accidentally, may have given the country an opportunity to address a problem it has long ignored. Some of Trump’s norm-flouting has gotten him in trouble. On other occasions, he’s done the previously unimaginable—and the world has kept spinning. Perhaps this might embolden the next president to give an uncommon inaugural address:

My fellow Americans, for generations presidents have stood where I stand now and built a tower of disappointment. They have stacked promise upon promise. We will not judge their heart. This great country calls us all to be generous. But it is not generous to the institutions created by our Founders to stretch them beyond their limits. Therefore, I will devote my presidency to two essential goals: ensuring your safety and your prosperity. I will partake in no ceremony enjoyed by my predecessors if it does not align with these goals. Instead, America will have the pleasure of coming to know my vice president, Cabinet officials, and husband. Congress too will enjoy the opportunity to show its generous temperament by returning to American government as an active and equal participant.

Cynics in the media would roll their eyes. The opposing party would accuse the president of shirking her duties. But the American people might appreciate the candor, the humility, and the pledge to focus on the work that matters.

wake congress from its slumber

Another of the jobs the president could step back from is his hands-on legislative role. It’s not a task the Framers intended, and it makes him a less, not more, effective spur for Congress. “The legislative process sets you up for failure,” Dan Bartlett says. “The playbook is: You start in the House, but that pushes you [away from the center] and then the legislation gets defined that way. If you try to only embrace the ‘process’ and not the actual law, House members get upset. Then it goes to the Senate, and the bill gets more moderate, at which point the president is accused of not having principles.” If the president didn’t have to weigh in at every turn, Congress would be forced to take the legislative lead, relieving pressure on the executive and returning to the model the Founders intended. The president could reserve his political currency until the end of the process, when a lot of the sticky issues have been thought through. He would no longer engage as one of many grubby negotiators, but with a preserved stature as the voice of the nation.

Let Them Play Golf

However the duties of the presidency are reorganized, the public and even the president’s political opponents should allow him to relax. There is nothing dumber than the national fixation with the president’s vacation schedule. The presidency never leaves the president. Even when he is on the golf course, he has the work coursing through his head. Moments of escape are healthy.