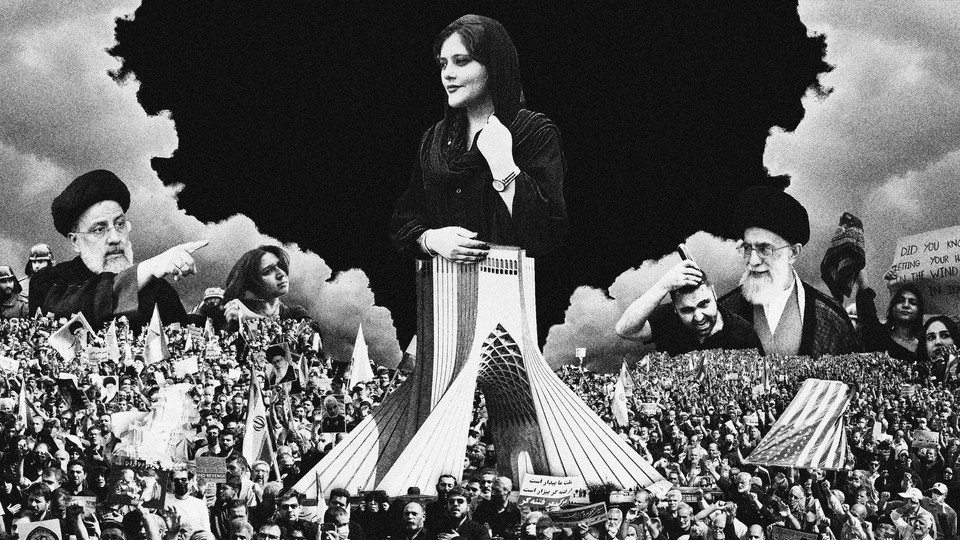

The Bonfire of the Headscarves

For Iran’s protesters, the fight for women’s freedom of choice is now synonymous with a desire to end the rule of the ayatollahs.

No one can predict how a revolution starts. Nor can anyone know when one injustice will be what causes a people’s fury to overcome their fear. In 2011, in Tunisia, a street vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, sparked an uprising by setting himself on fire. In 2022, in Iran, the death in police custody of a 22-year-old woman, Mahsa Amini, has brought Iranians onto the streets in every corner of the country.

Amini and her brother had traveled from Saqqez, a city in Iran’s Kurdistan Province, to visit relatives in the capital, Tehran, when, on September 13, the so-called morality police arrested her for improperly wearing her hijab, or headscarf. Three days later, she was declared dead. The authorities claim she died of cardiac arrest. According to a U.K.-based independent Iranian news site, the CT scans of her skull showed signs of fractures.

Each time I see the images of her lying in a coma in a hospital bed, I cannot help thinking that I could have been Mahsa Amini. I was a girl in Iran in 1981, when a law making the hijab a mandatory dress code for women first came into force, two years after the Islamic Revolution. And I was a teenager when the morality police began making the rounds, stopping and arresting people on a whim, sometimes on no more pretext than a few strands of hair peeking out from under one’s scarf.

One August day in 1984, thickly wrapped under my Islamic uniform and headscarf when the temperature was intolerably high and the water fountains in Tehran had been shut off in observance of Ramadan, I began thinking that I would not mind dying if those who had made our lives so miserable were to die along with me. I left Iran later that year, but today I feel what so many Iranian women feel: We are all Mahsa Amini.

Since her death, thousands have taken to the streets in a show of rage and solidarity that is rare even for a country that has known many such tumultuous moments. More than some past uprisings against the regime, this one has been remarkably broad-based and inclusive. The affluent residents of north Tehran have come out alongside the poor ones from the city’s south side. The youth are there—and so are their parents, even their grandparents. The metropolitan people are out, and so are the small-town folk.

The women of Iran are at the forefront—they who have most consistently resisted the regime’s tyranny and persisted in rebutting the myth that the hijab is an Iranian tradition. The sight of all the men at their side is a sign of the near-universal disdain for the regime’s official misogyny. With the risks these citizens are taking and the sacrifices they are making, they are proving that if any tradition needs defending 24 hours a day by armed men who have to beat people to embrace it, then it deserves to perish.

Even the celebrities who kept silent in the past are speaking up. Movie stars and sports figures are tweeting messages of support for the demonstrators—some even calling on the army to intervene on the people’s behalf. The popular musician Homayoun Shajarian, the son of a beloved master of Persian music, Mohammad-Reza Shajarian, projected an outsized image of Mahsa Amini as the backdrop to his latest concert—an act of defiance that prompted the audience to chant “Death to Khamenei” (Iran’s supreme leader).

All talk of ethnic or other divisions that once pitted one group against another in Iran is forgotten. For years, rumors about the threat of separatist movements, especially in Iranian Kurdistan, caused bitter debate. But the nationwide grief over the death of this young Kurdish woman, whose loss has been lamented in such unlikely parts of the country as the Turkish-speaking city of Orumiyeh, has overridden the old tensions. In the face of the common injustice that every Iranian experiences, ethnic differences seem insignificant.

No one in Iran today is setting fire to effigies of Uncle Sam or the U.S. flag. Instead, women are burning their headscarves in the street, on bonfires that men light for them. They don’t object to the hijab itself; they object to not having the right to choose whether to wear it. Somehow, despite the virtual absence of relations between Iran and the U.S. for more than four decades, those two vital American ideas—about rights and choice—have made their way into the country. People are marching through the streets not with the slogan “Death to America” but with a new one: “Death to the Dictator.” The people who once believed America was the Great Satan, the source of all evil, are now chanting “Our enemy is right here. They lie when they say it’s America.”

Forty-three years ago, Iran humiliated America before the world by parading in front of cameras the blindfolded U.S. embassy staff it had taken hostage in Tehran. Today, the Iranian people are humiliating their own leaders by defacing the murals of Ali Khamenei and tearing down his image from billboards.

These demonstrators are asking not for lower fuel prices, or better salaries, or fair elections—the demands of so many previous protests. In fact, they are not asking for anything at all. They simply want the regime to go.

Iranians’ aspirations for the rule of law date from long before the Islamic Revolution; they began more than a century ago with the country’s Constitutional Revolution. For nearly 20 years, the U.S. State Department has spent tens of millions of dollars to advance the cause of democracy in Iran. This investment is a pittance compared to the trillions America has spent pursuing wars in two of Iran’s neighboring countries, Iraq and Afghanistan, not to mention all of the blood spilled, yet American support for the dream of democracy has been vital—and may at last be yielding results.

The question is whether Washington is ready for this moment. Have America’s sponsors of Iranian democracy planned for what to do if they succeed?

Iran has reached its Ukrainian moment, the time when a people realize that they are willing to pay the price for their freedom. Iranians recognize that this is their fight, and—unarmed as they are—they are on the streets facing the regime’s paramilitary thugs. In social-media posts, some of this movement’s prominent activists have recorded video statements saying that they refuse to leave the country—whatever the future may bring, they’re there to stay.

The United States, through actions and not simply messages of support, must show that it cares as much about the Iranian people’s aspirations for freedom as about containing the regime’s nuclear ambitions. One step the U.S. could take would be to suspend its participation in the talks to restore the nuclear deal. That would be a signal to the ayatollahs that they have no chance of seeing economic sanctions relaxed as long as their goons are shooting their own people on the streets of Iran.

Like the Ukrainians, Iranians cannot win their freedom without the support of the U.S. and other Western nations. They are willing to make sacrifices, but that willingness and determination alone cannot win revolutions. Americans have waited four decades for Iranians to reject the regime’s propaganda and stop seeing them as the enemy. This is a historic opportunity for the two nations to forge a new bond if the U.S. chooses to support Iranians in their hour of need. Those who wish to see democracy regain momentum around the world must do their part.