The Pioneering Female Doctor Who Argued Against Rest

Physicians once advised menstruating women against mental exertion, fearing it would ravage their health.

For many years, rest was a common recommendation for women for all sorts of ailments, including one that arrived each month: their period. Women must rest not only their bodies during menstruation, but their brains, too. Mental exertion, the reasoning went, drained their energy and diverted it from where it really belonged, in their reproductive system.

Without rest, the minds of women were liable to drift to unacceptable places—like the voting booth. In 1912, Almroth Wright, the immunologist best-known for developing a typhoid vaccine, wrote a letter to The Times of London that laid out a case against women’s suffrage.

“No doctor can ever lose sight of the fact that the mind of woman is always threatened with danger from the reverberations of her physiological emergencies,” Wright wrote, referring to periods. “It is with such thoughts that the doctor lets his eyes rest upon the militant suffragist. He cannot shut them to the fact that there is mixed up with the woman’s movement much mental disorder; and he cannot conceal from himself the physiological emergencies which lie behind.”

This particular concern had reverberated among male doctors for decades, with little to counter it. But at least one doctor—Mary Putnam Jacobi—saw the problem differently.

At the end of the 19th century, Edward Clarke, a physician in Boston, perceived an alarming shift in American culture: More and more women were enrolling in universities. He argued that women could not handle the rigors of higher education, especially while on their period. “Girls lose health, strength, blood, and nerve, by a regimen that ignores the periodical tides and [the] reproductive apparatus of their organization,” Clarke wrote in his book in 1873, which received considerable attention.

The concept fit in nicely with the larger discussion about women’s health in the medical field. Women were seen as inherently weak and prone to sickness, and doctors prescribed rest for all manner of physical and psychological ailments. (This was also before exercise became a more popular remedy for certain illnesses.) Learning while menstruating, Clarke thought, risked illness and even infertility.

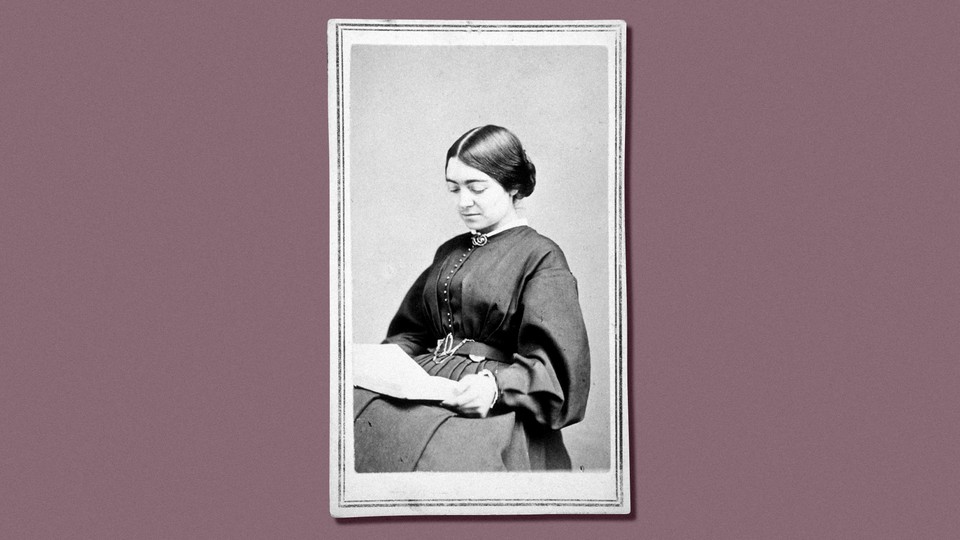

This argument didn’t sit well with Jacobi, then a physician in New York. To her, Clarke was utterly wrong. Jacobi was a well-regarded doctor, one of the few women practicing medicine in America in the 1870s. She came from a middle-class New York family, the eldest of 11 children. Her interest in anatomy emerged early, when as a young girl she discovered a dead rat in her family’s barn on Staten Island and, as she recalled, felt overcome with the desire to cut open the cadaver and take a peek inside.

Despite some resistance from her father, who worried higher education would abrade her femininity, Jacobi studied at the New York College of Pharmacy and then the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania, as it was known then, where she received a medical degree in 1864. Jacobi got a second medical degree at the École de Médecine in Paris, where she was the first woman to attend.

By these measures, Jacobi was a living contradiction of Clarke’s conclusions. The year Clarke published his book on girls and education, Jacobi was a lecturer at the Woman’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary and treating patients at the clinic. Those who disapproved of women practicing medicine sounded the warnings Clarke did; they argued that strenuous medical work threatened their feminine qualities and reproductive health.

In a rebuttal published in 1877, Jacobi thoroughly dragged Clarke. His recommendations, she wrote, lacked “experimental proof,” relied on “exaggeration of fact,” and served “many interests besides those of scientific truth.” In her view, Clarke’s assertions weren’t medical at all, but a deliberate attempt to bar women from classrooms and offices and to keep them in the home.

Sure, some women experience pain and discomfort during their period, Jacobi said, but menstruation doesn’t ruin the mind. In fact, women were more healthy when they were engaged in activity in general. Jacobi prescribed one of her patients, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, the author of “The Yellow Wallpaper,” a regimen of mental and physical activity for an ailment that now would likely be diagnosed as depression. Jacobi’s treatment proved more successful than the “rest cure” Gilman had previously received from a male doctor.

Clarke insisted that mental labor and menstruation were conflicting functions because they taxed the brain in similar ways. Jacobi said the opposite was true; menstruation was not so different from digestion, and no one needed a week’s worth of rest after a meal. Clarke argued that education exacerbated women’s emotions during their period; Jacobi countered that mental stimulation provided a salve for the discomfort. Unlike Clarke, she had data to back up her thinking. She had conducted a questionnaire of 268 women, she reported, and the results showed the effects of rest were “quite superfluous.”

“She really wanted to normalize and show a healthy female body during menstruation,” says Carla Bittel, a history professor at Loyola Marymount University and the author of a 2012 biography of Jacobi.

Jacobi’s rebuttal appeared years before the women’s suffrage movement picked up steam, and she quietly opposed suffrage at first. She believed women could achieve more equality by participating in higher education and serious professions—as she had—than by casting votes. Her thinking eventually changed, though, and she publicly joined the movement in the 1880s. She likened a functioning society to a healthy organism; when one part was excluded—women—the whole suffered. There were limits to this analogy: Jacobi didn’t believe the contributions of minorities, immigrants, and the working class played an equal part in maintaining a healthy society, Bittel says.

But her essay buttressed the fight against bad ideas about female biology, which were readily invoked by suffrage opponents as the movement moved into the 20th century. The perceived inferiority of women was at the core of the debate, and menstruation fit neatly as a predictable weakness. Just as Clarke had used physiology to reinforce female subordination, so did anti-suffrage activists during the height of the movement. “Opponents basically boiled women down to their sex, which basically means to their reproductive organs and function,” says Carolyn Skinner, an English professor at Ohio State University who studies the rhetoric of 19th-century American women physicians.

Twentieth-century suffragists were the picture of the kind of women Clarke feared. In March 1914, more than 300 women came to Capitol Hill, handing out small maps showing which states had already legalized women’s suffrage and taking turns addressing the members of the House Judiciary Committee, all men. One speaker, identified in congressional documents as Mrs. William Kent, came from California, which granted women the right to vote nearly three years earlier. Kent urged the lawmakers to pass legislation extending the same right to women across the country. “We will not rest until all the women are enfranchised,” she said.

For the next five years, suffragists from around the country protested and marched and even staked out the White House, signs held aloft, where President Woodrow Wilson, who once said he wasn’t aware women wanted the vote, would sometimes avert his eyes as his car rode past. As Kent vowed, they did not rest, and as they shaped the tide of a flourishing movement, these women subverted an old tradition designed to subdue them.

Although the notion that periods ravaged women’s mental capacity eventually faded from clinical study, whispers of it linger today. People who menstruate are still defined by and judged on their monthly cycles, ranging from stereotypical depictions in pop culture to insults from the White House. “Whether it’s comedic in some contexts or political in others, it becomes this way of diminishing women,” Bittel says. Still, menstruation has reached a normalization in public discussion that Jacobi, who died in 1906, probably never imagined. Some stigma persists, but no good doctor prescribes patients a week’s worth of bed rest out of fear that a little mental exertion might wreck their body.