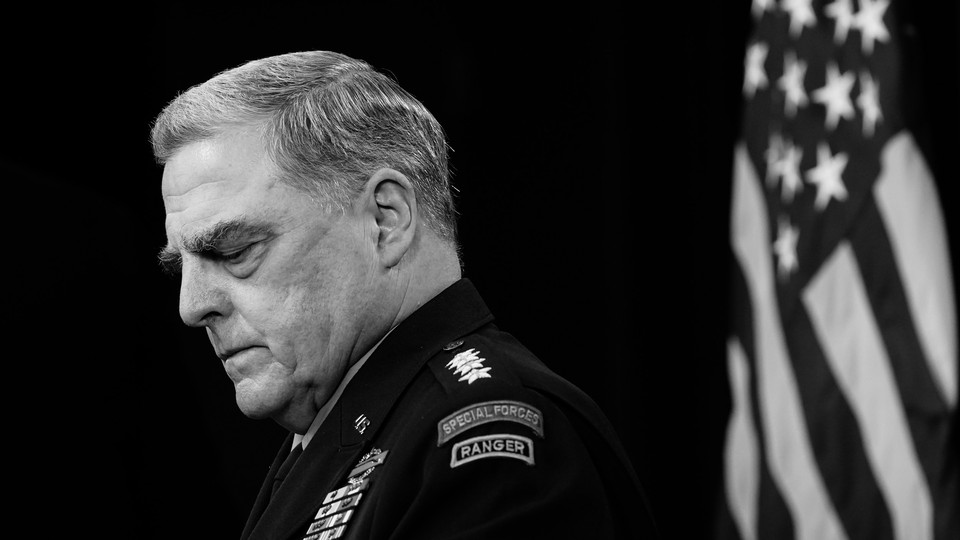

Trump Put Milley in an Impossible Position

The general stayed inside the lines—barely. The real problem is that he was in that situation at all.

Did the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Mark Milley, violate the Constitution? The answer, at least on the current available evidence, is no.

In a new book, Bob Woodward and Robert Costa write that Milley contacted his opposite number in China just before and just after the 2020 election. Milley, according to Woodward and Costa, was reaching out to General Li Zuocheng to calm jangled nerves in Beijing about the stability of the United States. Milley also reportedly called together a group of senior U.S. officers and made them affirm, one by one, that they understood that the procedure for the release of nuclear weapons had to include him.

A fusillade of hot takes greeted these revelations, almost all of them focusing on Milley’s contacts with Li. Many Republicans immediately interpreted Milley’s reassurances as betrayal and demanded that he resign or be fired. But it’s not just Republicans who are concerned: Retired Army Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Vindman, whom no one would mistake for a Trump supporter, tweeted that Milley violated the core American precept of civilian control of the military and therefore must go.

Milley’s conversations with Li are a concern not because they were unprecedented or a betrayal (as his critics claim) but because Milley felt the need to have them at all. Senior military-to-military contacts are normal and are an important part of building trust between nations, especially between adversaries. In the late 1990s, I had students from Russia in my Naval War College seminars. We valued their presence enough that when the Kremlin pulled them out after the war in Kosovo, I was sent to Moscow in hopes of creating more joint programs with the Russians that might include bringing those officers back. (I do not, of course, in any way represent the views of the Defense Department or the U.S. government.)

The fact that Milley knew his Chinese counterpart personally is not only a good thing in itself; such relationships exist for moments exactly like the ones described in the Woodward and Costa book. If Milley had information, as Woodward and Costa say he did, that Chinese military leaders were “rattled” by the chaos in Washington, then by reaching out to his peer he did exactly what he should have done.

One of the accusations against Milley is that somehow the chairman was going to betray American war plans to the Chinese. This is ludicrous, and even Senator Tom Cotton, a Republican China hawk, said that this accusation against Milley seemed far-fetched. Milley, invoking his personal relationship with his Chinese counterpart, told Li that he would hear about any military action from Milley himself. This is what reassurance and transparency looks like in a crisis.

The far more serious question is whether Milley inserted himself into the nuclear chain of command. Woodward and Costa write that Milley knew he was “pulling a Schlesinger,” trying to interpose himself in a nuclear process that does not, in fact, have a role for the chairman, in the same way that Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger had done in 1974 when he instructed the military to check any nuclear orders with him or Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

Even here, however, the situation is not as clear-cut as the Schlesinger example. Concerned that Richard Nixon was drinking heavily and under immense stress, Schlesinger functionally replaced the president as the ultimate authority for the release of nuclear weapons. Milley was somewhat more guarded; according to Woodward and Costa, the chairman “called a secret meeting in his Pentagon office on January 8 to review the process for military action, and said: ‘No matter what you are told, you do the procedure. You do the process. And I’m part of that procedure.’”

The chairman, however, is not part of that procedure. He is the president’s adviser, with no operational authority. When the president orders military action, the secretary of defense relays those orders to military commands. In the case of nuclear-weapon deployment, the president must only verify his identity, a process that requires one other person to certify that the orders and the codes are in fact coming from the commander in chief.

This is remarkably dangerous. Worse, it was designed that way. During the Cold War, the United States wanted the Soviets to understand that the president, even with only minutes of warning, could order nuclear strikes without a long and complicated procedure—especially if “the president” was whoever was left in the line of succession.

So what was Milley doing? When he said “no matter what you are told,” it is hard to believe that he did not mean “including by the president,” and that alone is a breach of civil-military tradition and an overstepping of his military authority. Unlike Schlesinger, Milley did not displace the commander in chief, but he did redefine the chain of command to include a previously nonexistent requirement that he be informed no matter what the civilian leadership told any U.S. military officer.

This doesn’t mean Milley should be relieved or fired. He made a judgment call in an unprecedented situation, and we should be glad for it. The Constitution of the United States has no provision for the control of planet-destroying weapons while a president is losing his mind and trying to overthrow the government itself. Even the Twenty-Fifth Amendment was meant to spackle the gaps in presidential succession in the case of death or disability. It does not countenance speedily removing the president from office against his will—especially while the vice president and the entire Congress are under armed guard from a violent mob carrying nooses and smearing feces on the walls of the Capitol.

Milley was looking at a civilian leadership in complete disarray, with the executive branch in the hands of a coterie of cronies—including an acting secretary of defense who by his own admission had no idea what was going on most of the time—and a president whose understanding of “the nuclear,” as he called our strategic deterrent, was childlike at best.

At the least, Milley was trying to insert a moment of pause into any possible escalation to disaster, and for that we should be grateful. His order was insurance against the chance that a raving Donald Trump, some hapless lieutenant commander, and the Acting-Temporary-Undersecretary for Advanced Defense Widgets could get together in the basement of the White House to transmit the codes to hell to the U.S. Strategic Command without anyone else knowing about it.

Milley didn’t “pull a Schlesinger,” but he was close.

What should we do about all this? As the defense expert Kori Schake and others have noted, the real problem here is that Milley was in this situation at all. As is almost always the case when civil-military relations become unstable, the civilians are the problem, and the civilians must provide the remedies. There are several possibilities, including passing a law to restrict the first use of nuclear arms, or in peacetime adding the requirement of a second confirmation to the president’s orders.

In the end, however, the answer lies in electing better leaders. Trump is gone, but he still leads a seditious and unhinged party. The Constitution, as James Madison warned us, was meant for a virtuous people, and if there is no virtue among us, “we are in a wretched situation” and “no theoretical checks, no form of government can render us secure.” It is incumbent upon us, the voters, to ensure that no military officer ever again faces even the possibility of a choice between obedience to the Constitution and the fate of human civilization itself.