Why Men Thought Women Weren’t Made to Vote

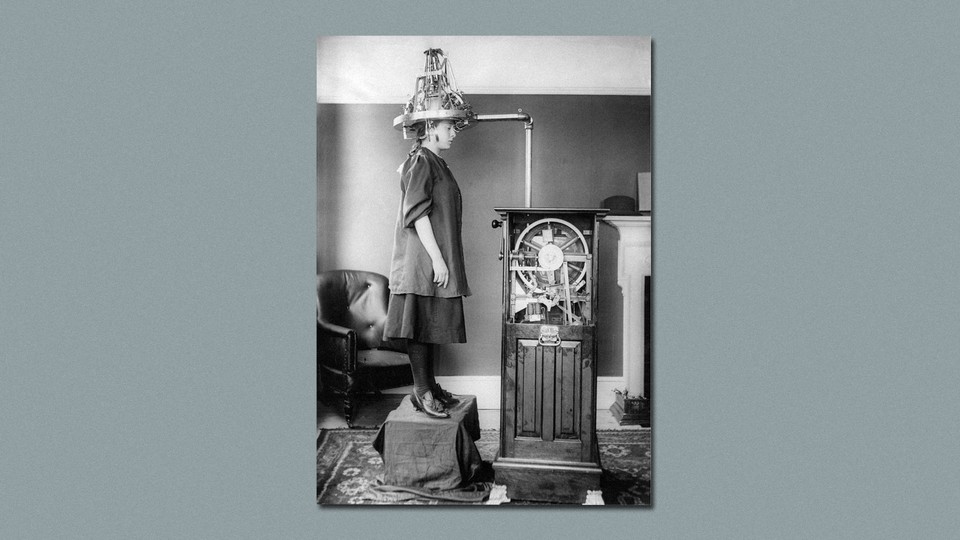

During the suffrage movement, conventional wisdom held that civic duty was bad for the ovaries.

William T. Sedgwick believed that no good could come of letting women vote.

“It would mean a degeneration and a degradation of human fiber which would turn back the hands of time a thousand years,” Sedgwick said in 1914. “Hence it will probably never come, for mankind will not lightly abandon at the call of a few fanatics the hard-earned achievements of the ages.”

A mere five years after The New York Times published Sedgwick’s warning, Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment, which legally granted American women the right to vote. Civilization didn’t come crashing down. But at the turn of the 20th century, many people listened to Sedgwick, a well-known professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

They believed him when he said—as other academics, doctors, and scientists did—that women shouldn’t vote because they were, quite literally, not made for it. According to the leading theory, mental exertion could jeopardize reproductive health. And if the science of the day asserted that women could become infertile if they did too much thinking, no man would want to send his daughter, sister, or wife to college or the office—and certainly not to the ballot box.

For those who opposed the suffrage movements in the United States and Britain, which unfolded in tandem, nearly every element of the female anatomy was seen as disqualifying, starting from the very top: their brains.

According to the mainstream science of the time, “Women simply had inferior brains, which made them unsuited to the rigors of voting,” says Cheryl Jorgensen-Earp, a professor at the University of Lynchburg who studies rhetoric in science and the British women’s-suffrage movement. “Anti-suffrage cartoons poked fun at women’s reasoning ability … which showed the interior of a woman’s head filled only with letters, puppies, hats, chocolates, and the faces of admiring young men.”

And if women overexerted their already inferior brains, the thinking went, their health could suffer. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, before studies of exercise and metabolism suggested otherwise, many people believed that the human body contained a finite amount of energy. This perception proved more inconvenient for women than for men, as it implied that women needed to channel their energy toward their reproductive system rather than their mind. If women were out voting and participating in politics and thinking, their ovaries would atrophy.

Such activity was especially dangerous while a woman was pregnant. “We must not forget pregnancy and lactation, both of which are a great strain on a mother’s vitality,” Sedgwick said. “Any further strain, like the responsibilities of the suffrage, is bound to be harmful to both mother and child.”

The effects of mental exertion only worsened during menstruation, which further destabilized women on its own. Periods, anti-suffragists argued, produced a temperament unfit for politics.

“For man the physiological psychology of woman is full of difficulties,” wrote the British immunologist Almroth Wright in a 1912 letter to The Times of London, which Sedgwick would later quote. “He is not a little mystified when he encounters in her periodically recurring phases of hypersensitiveness, unreasonableness, and loss of the sense of proportion.” Even menopause made women ineligible to participate in elections, Wright said, because it gave rise to “serious and long-continued mental disorders developing in connexion with the approaching extinction of a woman’s reproductive faculty.” Having a uterus seemed to be a lifelong disqualification.

There was also the matter of physical strength, which anti-suffragists believed was essential to political participation. “The object of government is the protection of person, property, and reputation from the foes which assail them,” Lyman Abbott, an American pastor, wrote in The Atlantic in 1903. “Nothing is law which has not authority behind it; and there is no real authority where there is not power to compel obedience.” If women couldn’t defend the nation through physical force, Abbott wrote, they shouldn’t be allowed to determine its policies with the ballot. Jorgensen-Earp says this argument was especially persuasive in the early 20th century, as the threat of war hung over the nation and Americans feared appearing weak to foreign powers.

To many suffragists, these arguments were complete hogwash, and they sought to dispel them as myths. But it was a restricted cause: “Votes for women” was, as a rule, understood to mean “votes for white women.” Many white suffragists, including some of the country’s leading figures in the movement, were outraged that black men had won the vote before white women. When they argued against sexist pseudoscience, they did not argue in the name of women of color.

With those arguments, suffragists sought to dismantle claims of their lesser intellectual ability with the power of prose, publishing a flurry of editorials and essays and delivering speeches at demonstrations and before Congress. “[The woman’s brain] is as rich in convolutions as is the man’s. Why should it not be? Her mother gave one half, her father gave the other half,” Mary Johnston, an author and founding member of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, wrote in The Atlantic in 1910. “Behind those two stand two men and two women; behind those four, four men and four women; behind that eight, eight men and eight women; behind that sixteen, sixteen men and sixteen women; behind that thirty-two—no use to go on … Is she deficient in mental power? Then her forbears, men and women, were so.”

To assertions of their physical weakness, they gestured to the men around them unable to enforce law with their might, whether because of their age or health. They pointed to powerful men whose small stature did not preclude them from entering politics. “Many men of Herculean powers of mind have been small and weak in body,” Elizabeth Cady Stanton, one of the most prominent American suffragists, said at the famous Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. “John Quincy Adams was a small man of but little muscular power, yet we know he had more courage than all the northern dough faces of six feet high and well proportioned that ever represented us at our Capitol.” In some cases, instead of arguing against the importance of physical strength, they demonstrated their own. They stood for hours outside the White Houses in inclement weather and withstood torture when they were jailed for picketing.

Anti-suffragists’ rhetoric did not vanish when William T. Sedgwick’s worst nightmare came true and Congress granted women the right to vote in 1919. It became diluted in the decades after, but dregs have stuck around. A century later, people continue to consider womanhood a handicap. Last year, a male physicist said at a conference that men outnumber women in physics because women are just worse at it. In 2017, Google fired a male software engineer who posted a memo to an internal message board arguing that women’s underrepresentation in the technology industry could be explained by biological differences between the sexes. And Jorgensen-Earp wonders whether perhaps a certain kind of discourse that is commonly derided today borrows from an old tradition.

“It is fun to contemplate whether minor modern irritations such as ‘mansplaining’ are based on some men’s belief that women are less mentally fit,” she says. “Or, heck, maybe they just like to hear themselves talk.”