The Obama Portraits Have Had a Pilgrimage Effect

One year after Kehinde Wiley’s and Amy Sherald’s paintings were unveiled, the director of the National Portrait Gallery reflects on their unprecedented impact.

In April 2018, the artist Wendy MacNaughton posted a picture titled Dispatch From DC on Instagram. It was a clever ink-and-watercolor drawing showing Rhonda, a security guard at the National Portrait Gallery, next to the newly unveiled portrait of Barack Obama by Kehinde Wiley. In a hand-printed caption, Rhonda is quoted recounting how an elderly lady had gotten on her knees and prayed in front of the portrait in the company of other visitors: “No other painting gets the same kind of reactions. Ever.”

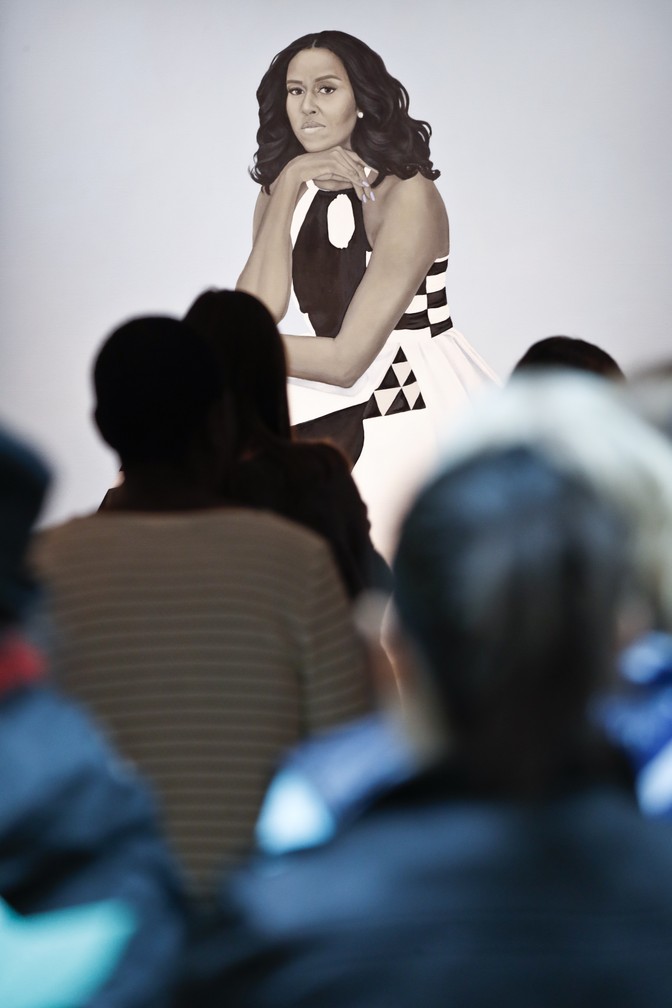

The image made the rounds online, which was not entirely surprising, because immediately after the unveiling of the Obama portraits, the museum’s attendance had tripled. A month before MacNaughton posted her drawing, 2-year-old Parker Curry had been captured on a smartphone gazing in awe at Michelle Obama’s portrait, painted by Amy Sherald. The resulting media sensation had led the girl’s mother to hire a publicist to manage all the requests for interviews. Mrs. Obama, Parker told Ellen DeGeneres in front of a live national audience, was probably a “queen.”

As the director of the National Portrait Gallery, I had a front-row seat to this “Obama effect,” and was trying to manage my dream scenario of watching thousands of visitors pouring through the doors. MacNaughton’s illustration confirmed what I had begun to suspect: Viewing these paintings was turning into a form of secular pilgrimage, and the museum was becoming even more popular as a communal gathering place. The question I asked myself, given that we had hundreds of portraits of notable Americans from George Washington to Beyoncé, was Why? What was really happening?

Pilgrimage has been described as one of the oldest forms of tourism, undertaken by the faithful of all the world’s major religions to restore a sense of order and meaning to their everyday lives. Anthropologists have suggested that such a journey involves people leaving the familiarity of home and undergoing a liminal experience, a disorienting voyage—to Mecca since the time of the Prophet Muhammad, or Jerusalem in the Middle Ages, for example—that brings them to the threshold of spiritual change. In their heightened psychological awareness, pilgrims develop a sense of communitas, in which strangers on the same journey feel a sense of kinship with one another, allowing cultures to cross paths both real and symbolic. They return home with a renewed sense of hope.

At first, pilgrimage was understood as religious, but later scholars allowed for the idea of a secular journey that was just as powerful. Elvis Presley’s home, Graceland, and Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, for example, have been called sites of contemporary pilgrimage.

The National Portrait Gallery’s building, where the Obama portraits are on view, was in many ways made for transformative change. Designed in the 19th-century Greek Revival style of architecture to house the U.S. Patent Office, it was modeled on the Parthenon in Athens and intended to symbolize the highest ideals of Athenian democracy, whereby power is in the hands of the people, and the rule of law allows industrious individuals the freedom to acquire wealth by their own means. Originally meant to house a “church of the Republic,” in the words of the city planner Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the Patent Office was envisioned as a temple of industry and national pride honoring America’s technological superiority. In 1958, Congress gave it to the Smithsonian Institution to become, in part, the home of the National Portrait Gallery. In many ways, it is apropos, because at the museum we like to say that America’s greatest invention has been its people.

Long before America signed the Declaration of Independence and formally broke with Britain, portraiture was an elite art form reserved for royalty and European aristocracy. Considered an investment in advertising a family’s influence, likenesses by fashionable artists were housed within palaces and family estates to be seen by only a privileged few. The founding of the National Portrait Gallery in Britain in 1856, however, marked a shift. One of its founders, the Earl of Stanhope, advocated private elitism as a vehicle for public pride; a celebration of British worthies, he believed, would make the museum a destination for secular enlightenment.

That idea of artistic patronage for national benefit crossed the Atlantic when the American industrialist Andrew Mellon stipulated in his will that his collection of fine portraits should be gifted to the nation and form the basis of a portrait gallery in Washington. The museum was founded in 1962 and nested within the Smithsonian. Congress endowed the National Portrait Gallery with the additional “serious national purpose” of answering the question, What is an American?

The museum tried to answer this question, accompanying its public opening with a book titled The American: This New Man. In it, the historian Oscar Handlin, quoting the French-American writer St. John de Crèvecoeur, defined an American as someone who had heroically left behind the “ancient prejudices and manners” of the Old World—this, despite the fact that the ideas of European racial superiority had transferred themselves to the New World and been used to justify Native American genocide and slavery. Portraiture as an elitist art form had also crossed the Atlantic, but just like the European credo of noblesse oblige, American portraiture favored white men who owned land.

The result was that the museum’s collection itself was largely pale and male, with the stories of first contact, immigration, and bondage hard to come by or altogether absent. While Mellon had donated a rare portrait of Pocahontas, and the Harmon Foundation a posthumous painting of Harriet Tubman, it would take another few years to add Frederick Douglass and a decade to add Sojourner Truth. Restricted in no small measure by policies that prohibited photography or portraits of anyone who had not been dead for at least a decade, the museum’s presentation of E pluribus unum (“Out of many, one”), was more like E pluribus lecti (“Out of many, some”).

Today’s National Portrait Gallery includes Jimi Hendrix and Marilyn Monroe along with Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr. Free admission allows visitors to decide for themselves whom they want to admire, and creates a community that might share a cultural discourse tilted more toward Hollywood than toward holy scripture. Where once religious pilgrims carried guidebooks along with devotional texts to direct their journey, visitors today carry museum guides along with mobile phones. Leaving the familiarities of their daily lives, they travel into these templelike spaces to experience something emotional, bigger than themselves. Echoing the prescribed routes of religious pilgrimage, visitors to the National Portrait Gallery might find a connection with communitas.

The date of the Obama portraits’ unveiling, deliberately chosen by Barack Obama, was February 12, Lincoln’s birthday. The 44th president had made no secret that he admired the 16th, having launched his presidential campaign in Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield, Illinois; held the Lincoln Bible at his swearing-in; and often remarked that Lincoln’s abolition of slavery had made his presidency possible. Like Lincoln, the first president to savvily use photography of himself to connect with the American people, Obama’s presidency had been marked by an understanding of the power of portraiture.

Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, the artists the Obamas had chosen, were the first African Americans to paint the portraits of a president or first lady for the National Portrait Gallery, and from the moment of the unveiling, it was clear that both had borrowed from, and broken with, the canon of traditional portraiture. Wiley chose to seat the president in a chair, wearing a suit but no tie, looking directly out of the canvas. The pose is similar to that of George Peter Alexander Healy’s Abraham Lincoln, Elaine de Kooning’s John F. Kennedy, and Robert Anderson’s George W. Bush, all portraits that Wiley had seen on walks through the galleries. But it was the background of rampant foliage and flowers symbolizing periods of the president’s life—chrysanthemums for Chicago, jasmine for Hawaii and Indonesia, African lilies for Kenya, and rosebuds for love—that was so extraordinary, making Obama appear at once timeless and contemporary.

The portrait of Michelle Obama elicited more commentary. Attired in a geometric-patterned dress by the designer Michelle Smith, which reminded the artist of modernist art and Gee’s Bend quilts created by the descendants of slaves, the former first lady was presented as both modern and historical. The rendering of her skin as gray, as the New York Times art critic Roberta Smith wrote, “introduces the notion of double consciousness, the phrase coined by W. E. B. DuBois to describe the condition of anyone living with social and economic inequality.” Or, as the critic Antwaun Sargent noted more succinctly in W magazine, what viewers were witnessing were “visions of black power [shaking] up a gallery of white history.”

Watching viewers in front of the portraits, it’s clear that the celebrity of the Obamas cannot be underestimated. As Michael Dyson of Georgetown University has remarked, Barack Obama, as the first African American president, “shocked the symbol system of American politics.” In the gallery, his black body palpably ruptured America’s white ruling class and served as a poignant expansion of what blackness and presidential power could be in America—and maybe, in the eyes of the museum’s new pilgrims, what America could be, too.

Michelle Obama’s portrait, meanwhile, shares resonance with the former first lady’s instant best seller of an autobiography, which, as the writer Emily Lordi noted in The New Yorker, “draws on the literature of black women’s self-making.” In her depiction of Obama, Sherald turned traditional portraiture on its head; for both women, being “seen” via portraiture appears to be an important step in claiming their space. Certainly when Parker and another little girl called Raegan last Halloween dressed as Michelle Obama and Amy Sherald, respectively, and posted their costumes on Instagram, the elitist tradition of portraiture was transformed by their joyful faith that they, too, could grow up to become such strong women. (Never doubt that portraiture can change the world!)

Today, the lines to the museum continue, with people of all types queuing up to take a selfie in front of the portraits and buy merchandise in the store—tripling sales last year. The portraits have become a pop-culture reference, replicated in Peeps dioramas, lunch bags, children’s clothes, and a host of online memes. It was with some hilarity that I saw myself portrayed on an episode of Scandal enabling Olivia Pope, played by Kerry Washington, to walk through a faux National Portrait Gallery to see her picture being gazed at by two little girls, à la Parker and Raegan.

There is something fitting in the fact that portraits of the first black president and the first black first lady have rekindled a sense of pilgrimage within a space originally intended to elevate secular America. Visitors to the paintings take for themselves a special moment in our galleries that is not only about transition but also about potentiality—a pilgrimage from the past and into the future, with a brief moment to reflect. As Savannah, one of our visitors, said, “To me they are period icons, and it remains to be seen if they are documents of a fleeting moment, or a new century.”

An expanded version of this essay will appear in The Obama Portraits, a forthcoming National Portrait Gallery publication.