When American Suffragists Tried to ‘Wear the Pants’

Starting in the 1850s, proponents of the movement for women’s rights traded their long dresses for bloomers—and paid a heavy social price for it.

In 19th-century America, the struggle for women’s rights—including the right to vote, enshrined nearly 100 years ago in the Nineteenth Amendment—often went hand in hand with other social and political goals: from abolishing slavery and securing Native American land rights to promoting temperance and championing the dress-reform movement. Dress reformers proposed comfortable and healthful alternatives to confining garments such as corsets and crinolines, the cagelike steel underskirts that characterized female fashion at the time.

Chafing against clothing norms was, of course, not quite the same thing as rebelling against the patriarchy, but the two issues frequently overlapped, starting in the mid-1800s. Women demanded physical freedom along with other, less tangible liberties, and many early feminists embraced what was euphemistically known as “freedom dress”—or, in other words, pants. But rather than spurring the suffrage movement forward, the garment prompted widespread backlash from a society that saw it as a sign of moral decay and a threat to male power.

At a time when long, voluminous skirts were standard, pants for women existed only on the fringes of fashion, in utopian communes and health resorts. They might have stayed there if not for Elizabeth Smith Miller. The daughter of wealthy abolitionists, Miller had the confidence to break the rules and the privilege to get away with it. In an 1892 essay published in The Arena, she recalled an experience she had in the spring of 1851:

While spending many hours at work in the garden, I became so thoroughly disgusted with the long skirt, that the dissatisfaction … suddenly ripened into the decision that this shackle should no longer be endured … Turkish trousers to the ankle with a skirt reaching some four inches below the knee, were substituted for the heavy, untidy, exasperating old garment.

Shortly thereafter, Miller wore this unconventional costume on a visit to Seneca Falls, New York, where she stayed with her cousin Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Stanton and her friend and neighbor Amelia Bloomer “at once joined me in wearing the new costume,” Miller recalled. Bloomer, a temperance activist and abolitionist, had launched a newspaper for women, The Lily, following the first women’s-rights convention, which was held in Seneca Falls in 1848. When Bloomer published an editorial in praise of the new outfit in the April 1851 issue, circulation soared, and she was inundated with requests for patterns from around the country. Thus, the “freedom dress” got a new name: the bloomer.

Today the term bloomer is usually applied to baggy, bifurcated undergarments. But the original bloomer costume was a two-piece ensemble resembling the shalwar kameez of Central and South Asia. Shortly after the bloomer’s appearance in The Lily, the British humor magazine Punch described it “as a sort of shemale dress … trousers tight at ankles, and for [the] most part frilled; tunic descending with some degree of brevity perhaps to [the] knees, ascending to [the] throat.” Though this “masquerade frippery” was a dangerous harbinger of “female radicalisms,” in Punch’s words, the magazine acknowledged that it had some merits: Namely, it freed women from disfiguring corsets and crinolines. But while health concerns were a socially acceptable reason for reforming fashion, for many, political ideology was not.

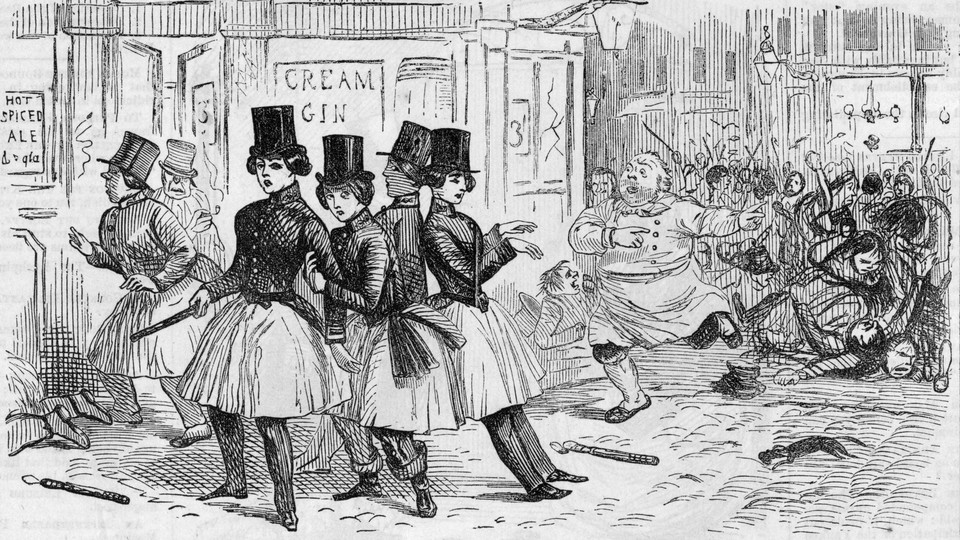

Within weeks of its first appearance in The Lily, the bloomer reportedly spread as far as California and Texas. The American suffragist Hannah Tracy Cutler introduced the bloomer to Britain when she wore it at the World’s Peace Congress in London in August 1851. The bloomer also conquered popular culture in the form of caricatures, songs, and plays praising or mocking it—and usually misrepresenting its appearance. The term bloomerism came to be inevitably—if incorrectly—associated not just with wearing trousers but also with other supposedly deviant (for women) behaviors, such as smoking, drinking, gambling, serving in the military, and abandoning husbands and children. As Bloomer herself pointed out, wearing traditionally male garments suggested an across-the-board “usurpation of the rights of man”—notably, the right to vote.

Women who dared to wear bloomers faced what the American suffragist Mary Livermore described as a “daily crucifixion.” When Stanton and Miller strolled through Seneca Falls in their bloomers, they were “followed by a crowd of boys yelling, singing, and laughing, while every door and window was lined with staring faces,” the suffragist Mary S. Bull remembered. Though Stanton later recalled that she had felt “as joyous and free as some poor captive who has just cast off his ball and chain,” her young sons didn’t want to be seen with her. Her father banned the bloomer costume from his house. Her older sister “actually wept,” Stanton reported to Miller in a letter, adding that her husband, Henry, a New York state senator, had discovered that “some good Democrats said they would not vote for a man whose wife wore the Bloomers.” Stanton confessed to Henry in another letter that she feared “the short dress”—as bloomers were commonly referred to—“will cost me the loss of my kin.” After two years, she gave it up, resuming the “uncomfortable, inconvenient, and many times dangerous” garments of her sex, as she described them to her son Neil in a letter. “Had I counted the cost of the short dress,” she told Miller, “I would never have put it on.”

Although Stanton had “passed a most bitter experience in the short dress,” her friend Susan B. Anthony was nonetheless determined to try it out. On February 16, 1854, Anthony wore her bloomers around Albany. At the end of the day, she complained: “I have … been in the streets and printing offices all the day long; had rude, vulgar men stare me out of countenance, and heard them say as I opened the doors, ‘There comes my Bloomer!’ Oh, hated name!” As Stanton told Lucy Stone, another suffragist who had tried, then given up, the bloomer: “We put the dress on for greater freedom, but what is physical freedom compared with mental bondage? By all means have the new dress made long.” Anthony agreed, though her experience in the bloomer had taught her a valuable lesson: “that women can never compete successfully with men in the various industrial avocations, in long skirts. No one knows their bondage save the few of us who have known the freedom of short skirts.”

Miller, too, eventually abandoned the bloomer. Her father was elected to Congress in 1852, and her bloomer costume allowed her to navigate the filthy streets of Washington, D.C., in cleanliness and comfort, and “to carry my babies up and down stairs with perfect ease and safety.” But while “the dress looked tolerably well in standing and walking,” when seated, “a more awkward, uncouth effect, could hardly be … imagined,” she admitted. Eventually, she had her skirts “lengthened several inches and the trousers abandoned,” though she continued to eschew corsets, long trains, bustles, high heels, and chokers.

By 1859, even the bloomer’s namesake had finally forsaken it. “In the minds of some people, the short dress and woman’s rights were inseparably connected,” Bloomer wrote in 1895. “With us, the dress was but an incident, and we were not willing to sacrifice greater questions to it.” The bloomer’s demise was part of a larger fashion reckoning, as dress reformers came to believe that their shocking sartorial experiments were unhelpful distractions from more pressing issues. In 1865, the National Dress Reform Association actually disbanded amid concerns that negative attention on dress reform was holding back other causes members held dear. Going forward, American suffragists largely strove to conform to fashion rather than upend it, rebranding themselves as respectable women instead of radicals. Instead of inviting unflattering comparisons to men, suffragists now strove to look as feminine—and, thus, as harmless—as possible.

While Amelia Bloomer’s name became a punch line, Susan B. Anthony would be remembered for a much different fashion statement: a demure red shawl, one example of which survives in the Smithsonian. When the National American Woman Suffrage Association convention met in Washington in 1898, media coverage focused on Anthony’s trademark shawl. “It is silk crepe of exquisite fineness, with long, heavy knotted fringe,” the Evening Star reported. “For full thirty years Miss Anthony’s red shawl has been the oriflamme of suffrage battle. She wears it with the grace of a Spanish belle.”

Highly visible without being flamboyant, Anthony’s shawl was arguably a secret weapon in making progressive feminism palatable to a wider audience. At an appearance in Philadelphia in 1905, “the figure of Miss Anthony was simplicity itself,” The Philadelphia Press reported. “That bonnet, with the kind blue eyes beneath it, those spectacles, that plain dress and quaint red shawl, and, above all, that sweet, gentle voice, spelled ‘mother’ as plainly as the fine word ever was written. Not a hint of mannishness but all that man loves and respects. What man could deny any right to a woman like that?”