RBG’s Fingerprints Are All Over Your Everyday Life

She expanded the possibilities of family life and work—for women and for men.

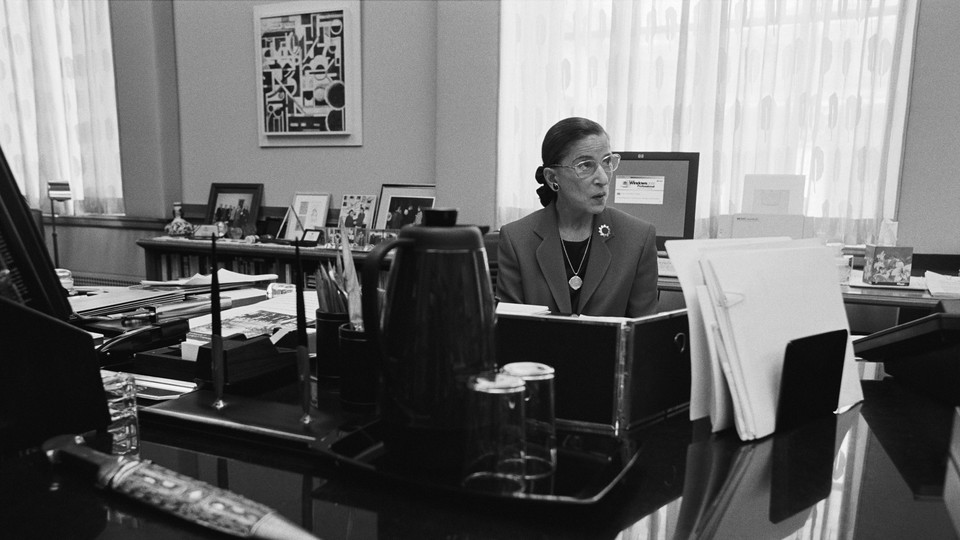

In her 87 and a half years, Ruth Bader Ginsburg left a significant mark on law, on feminism, and, late in her life, on pop culture. She also left a significant mark on everyday life in America, helping broaden the sorts of families people are able to make and the sorts of jobs they’re able to take. Her legacy is, in a way, the lives that countless Americans are able to live today.

Ginsburg achieved the status of celebrity as a Supreme Court justice, and during her tenure she cast votes in support of Americans’ ability to get an abortion and to marry someone of the same sex. But her legal legacy can be traced back to her work as a litigator with the American Civil Liberties Union in the 1970s, when she and others won a string of groundbreaking sex-discrimination cases challenging laws that governed quotidian parts of American life and now seem medieval.

Those laws implied a narrow view of gender roles within families. “At the time RBG was arguing, laws that made explicit gender distinctions were common. Widows get this; widowers don’t. Wives get this; husbands don’t,” Kathryn Stanchi, a law professor at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas, wrote to me in an email.

Ginsburg successfully advocated in court for, among others, a father who was denied Social Security survivors benefits after the death of his wife, because the law dictated that widows were eligible but widowers were not; a woman in the Air Force whose husband was denied a spousal allowance that military wives were automatically entitled to; and an unmarried man who was denied a tax deduction for the expense of hiring a caregiver for his elderly mother, since that deduction was reserved for women, divorced men, and men whose wife was incapacitated or deceased. The laws in question didn’t account for people in those circumstances; now, because of Ginsburg, they do.

Her litigation wasn’t about a series of isolated inequities, though: Ginsburg’s core argument was that “equal protection” under the law, as promised by the Fourteenth Amendment, covered discrimination based on sex. One unconventional but shrewd strategy she used was to focus on how such discrimination harmed men. “Rather than asking the Court to examine inequalities facing women, where nine men were very unlikely to be sympathetic, she asked them to look at inequalities affecting men, because she thought it was more likely that they would recognize those as problematic,” Michele Dauber, a law professor at Stanford University, told me.

This attention to the law’s treatment of men was not merely strategic, but also a component of Ginsburg’s larger legal project of demolishing the norms that steered women toward caregiving and men toward work. “The breadwinner-homemaker model is built into the structure of American society and American law at a very deep level,” says Joan C. Williams, a professor at UC Hastings College of the Law. One of Ginsburg’s crucial contributions to American feminism, Williams told me, was the insight “that you had to talk about these as a set of matched stereotypes, and attack them both at once.”

Ginsburg’s approach helped alter the way women were able to make their way in the world. Before the mid-’70s, they were often denied access to their own credit cards, “on the presumption that their husband controlled the family’s financial assets,” Patricia Seith, a researcher specializing in congressional legal history, told me. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 banned such discrimination, which had extended to mortgages as well. “Ginsburg paved the way for legislation such as ECOA,” Seith said.

The legal precedents that Ginsburg helped establish in the ’70s in a sense shaped the way households are set up today. For instance, female breadwinners are now much more common than they were several decades ago. “She’s not responsible for every single woman individually deciding to go get a job, but she did cultivate the conditions by which, if you chose to do so, you have full access to the benefits that your employment provided,” says Melissa Murray, an NYU law professor.

The accumulation of new protections won by Ginsburg and others have allowed many Americans to envision versions of family life beyond the breadwinner-homemaker binary. Her legacy “isn’t just Social Security or tax exemptions, though those are huge in their own way,” said Stanchi, the UNLV professor. “It is the ability to perform your gender as you wish, whether that is women working outside the home, … men staying home and caring for children, men loving other men, women loving other women.”

Of course, the United States has hardly reached anything resembling gender equality. Men are still more than twice as likely as women to be the higher earner in straight couples, and women spend, on average, over an hour more than men on caregiving and housework each day. The American family currently “looks a lot less different than we tried to make it,” said Williams, referring to the work that she and others have done. “But it looks a lot more different than traditionalists would have it.”

In that sense, Ginsburg’s legacy is expansive. When I asked Dauber, the Stanford professor, about the specific, concrete features of daily life that are different now because of Ginsburg, she said, “It’s the right to hold specific jobs. It’s the right to be a lawyer, the right to be a doctor. It’s the right to attend elite colleges, or any college. It’s the right to participate in sports. It’s everything that came after the idea that it was inappropriate to make distinctions based on sex alone … It’s not one thing that’s different—it’s everything that’s different.”