The Brilliant, Playful, Bloodthirsty Raven

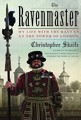

A new book from Christopher Skaife is a beguiling, fascinating, and highly amusing account of the strangely magical birds.

I can make a passable imitation of a raven’s low, guttural croak, and whenever I see a wild one flying overhead I have an irresistible urge to call up to it in the hope that it will answer back. Sometimes I do, and sometimes it does; it’s a moment of cross-species communication that never fails to thrill. Ravens are strangely magical birds. Partly that magic is made by us. They have been seen variously as gods, tricksters, protectors, messengers, and harbingers of death for thousands of years. But much of that magic emanates from the living birds themselves. Massive black corvids with ice-pick beaks, dark eyes, and shaggy-feathered necks, they have a distinctive presence and possess a fierce intelligence. Watching them for any length of time has the same effect as watching great apes: It’s hard not to start thinking of them as people. Nonhuman people, but people all the same.

The most celebrated ravens in the world live at the Tower of London, on the River Thames, an 11th-century walled enclosure of towers and buildings that houses the Crown Jewels and that over the ages has functioned as a royal palace, a zoo, a prison, and a place of execution. Today it is one of Britain’s most visited tourist attractions, and its ravens amble across its greens entirely unbothered by the crowds, walking with a gait that Charles Dickens—who kept ravens—described as resembling “a very particular gentleman with exceedingly tight boots on, trying to walk fast over loose pebbles.”

I met Christopher Skaife a few years ago while recording a radio program about Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven.” A jovial, bearded man, he’s one of the yeoman warders at the Tower of London. As such he is a member of an ancient and soldierly profession. For the past 13 years he has also been the site’s ravenmaster, which easily tops my list of favorite job titles (unicef’s “head of knowledge” comes in second). On Twitter, as @Ravenmaster1, he curates a much-loved feed packed with images of the birds in his care: raven beaks holding information leaflets, photos of the feathers on their broad backs, close-ups of their varied expressions, videos of their gentle interactions with him. A born storyteller with a gift for banter honed by years in the British army, Skaife has written a book that is far from a dry monograph about the species or a sentimental love letter to his birds. His beguiling, fascinating, and highly amusing account is full of details of the ravens’ everyday care, and details of his own life too, along with musings on how it is possible to feel happy and at home living and working in the fishbowl of a busy tourist attraction in the middle of London.

There’s joy in The Ravenmaster, as well as tragedy, obsession, and a rare tenderness toward Skaife’s avian charges. On his watch the ravens have been given dedicated aviaries and fed a diet that no longer consists merely of scraps from Smithfield Market but includes rats, day-old chicks, offal, boiled eggs, unshelled peanuts, fish, and rabbits. Dog biscuits soaked in blood are a favorite. Their wings are also less severely clipped than they were in the past, giving them a greater ability to fly. Now they can flap up to the roofs of the Tower buildings, and Merlina, the raven most bonded to Skaife, flies so well that she regularly spends time outside the Tower walls. “They need freedom, but they also need protection,” Skaife says of his ravens, as a soldier would speak of the British people. His new regime has been a great success, though changes to the wing-clipping routine have resulted in several chases to retrieve ravens gone awol. One bird was returned to him—alive—inside a gym bag.

Skaife didn’t train as a scientist, but living with the Tower ravens has given him deep insight into their minds and characters. Studying ravens in the wild is hard, though not impossible. They’re wide-ranging creatures, and usually highly suspicious of humans, who have spent centuries persecuting them as vermin believed to threaten livestock. Much of what we know about them has come from studying captive ones, like Konrad Lorenz’s raven, who famously would call his own name—“Roah!”—to Lorenz, while using proper raven calls to talk to his conspecifics. Keeping a raven is not like keeping chickens or doves; as the raven expert Bernd Heinrich has explained, their keepers more commonly see them as children, partners, or best friends. What’s more, the birds tend to be proficient trainers of their human handlers, rather than the other way around. They are not always easy to live with. I once met a man who laughingly described life with his raven as being a little like sharing a house with a psychotic toddler wielding a chisel.

Skaife calls attention to the birds’ beautiful contradictions. In sunlight their dark feathers shine with the iridescence of oil on water. They can be friendly, curious, even loving. In the wild they’ll take turns sliding down snowbanks and make toys out of sticks. At the Tower they play games of KerPlunk, pulling the straws free from the tube to retrieve a dead mouse as their prize. Yet, as that special raven edition of KerPlunk suggests, they’re also birds of gothic darkness and gore, the birds that followed Viking raiders in quest of fresh corpses and that feasted on executed bodies hung from roadside gibbets. You might visit Skaife’s charges in the Tower and watch, entranced, as they gently preen each other’s nape feathers, murmuring in their soft raven idiolect—but you might also see them gang up to ambush a pigeon and eat it alive.

Though ravens brought messages to humans in Assyrian, Mayan, and ancient Japanese mythologies, and were the emissaries of the gods Apollo and Odin, they are complex beings with their own minds and their own desires, a fact that can be hard for us to get our heads around. In his book-length study Mind of the Raven, Heinrich tells the story of a Colorado woman working outside her cabin who was disturbed by an incessantly calling raven that flew low over her to land on rocks nearby. The bird’s behavior was so unusual that she began to wonder whether it was trying to tell her something. Scanning her surroundings, she saw a cougar some 20 feet away, crouched and ready to spring. Of course she assumed that the raven was warning her of the danger. But Heinrich posits that the raven was likely communicating with the predator, leading it toward easy prey. We so readily put ourselves at the center of the tales we tell. Ravens help remind us that sometimes we’re merely walk-ons in someone else’s story.

Skaife is a man familiar with his own contradictions. He joined the British army in 1982, after his teenage tearaway years, to become a machine gunner and then a drum major in the infantry. Only after many years’ service did he apply to be a yeoman warder at the Tower. The ravenmaster at the time needed a new assistant; he sent Skaife into a small enclosure with two birds in it, instructing him not to show any sign of fear. He watched approvingly as one raven flew down and perched by Skaife, dipping its head and calling. The bird had accepted his presence. Skaife acquired a new job, in addition to his yeoman-warder duties.

Thus began an obsession so all-encompassing that the stories he tells about his old life in the army somehow always blend into what he is telling us about ravens. He is well aware that he’s making the ravens into an image of himself and vice versa—but also that his playful parallel is apt. Ravens, like soldiers, are heavily armed, clever, and tactically proficient, and they thrive on routine. They possess an idiosyncratic sense of humor, grabbing and pulling at the tails of predators (eagles, say, or wolves) to annoy and distract them. They display a certain bloody-mindedness, and forge intensely strong bonds with one another.

They also cleave to social hierarchy. Many researchers have become very invested in the whys and wherefores of ravens’ dominance relations, though I confess I’ve always found nearly every other aspect of their lives more fascinating. In Skaife’s telling, the shifting social structure of his ravens plays out like a nail-bitingly intense soap opera, and woe betide the handler who can’t keep up. One night Skaife made the error of putting the ravens to bed in the wrong order; chaos ensued. Hierarchy played a part in the disaster, but so did age. Young ravens are intensely interested in new things, but the older the birds get, the more neophobic they become, until anything out of the ordinary disturbs them. It’s tempting to draw comparisons to our commonly held conviction that conservative tendencies increase naturally with age.

Crucially, Skaife is a guardian not only of the ravens but of the Tower and of the legends that endow those venerable stones with meaning. He gives visitors talking tours, and part of his training was to learn by heart a detailed, 90-minute historical narrative of dates and events known only as “the story.” Its structure is sacrosanct, though personal elaborations are permitted. The ravens are not here for entertainment, the story goes. They are of the utmost importance: Should the ravens ever leave the Tower, it will crumble into dust, and great harm will befall the kingdom.

This account of the ravens’ presence has long been assumed to date back at least to the 17th century, the time of Charles II. Wild ravens would almost certainly have been a feature of the Tower in its early years, but, as Skaife reveals in his book, the presence of captive ravens at the Tower likely began only in the late 19th century. He wonders whether their advent may have been influenced by the Dickens-inspired fashion for pet ravens at that time, and believes that the first ravens were brought in simply to add to the tourist experience; they recalled the deaths and grisly past of the Tower and gave visitors a satisfying frisson of horror. But soon the raven set-dressing became a central part of the myth of the Tower—an entirely invented tradition, like so many that we presume sprang from time immemorial. Such traditions have a deeper purpose, and this legend’s telling and retelling by the yeoman warders renders it a kind of truth. The Tower ravens are a perfect coincidence of natural and national history, a seemingly organic imprimatur of the primacy of the state.

Lately, witnessing the political situations in Britain and America, I’ve been thinking a lot about national identity. So often it seems to be conceived as a kind of indivisible essence that has its roots in the past but is always under threat in the present. It is built on stories about an “us” and a foreign “them,” and on a sense of belonging anchored in an imagined land of yore, rather than nurtured gradually by personal attachment to a landscape. Objects from that revered past are ceaselessly recruited into the stories: ancient edifices, archaeological finds, prehistoric sites. All have the peculiar power to confirm the existence of a continuous national identity, no matter how remote those objects’ origin, or how different our lives and thoughts are from the lives and thoughts of those who built them.

Reading this book, I began to see how perfectly the Tower ravens fit into this form of story. To everyday visitors, a raven is a raven is a raven, and the ravens on the lawn are indistinguishable not only from one another, but from those ancient ravens of lore and legend, beings untouched by the weary hand of time. In truth, each of them is a many-sided individual. Skaife is doing us, I think, a small political service by introducing us to the quirks and histories of every bird in his care; he is letting us love them in a way that makes them more than mere symbols. Ravens have long been regarded as messengers, and the message the birds in this marvelous book have given me is this: Perhaps, by paying much closer and more careful attention to the reality of the things we unconsciously use to claim the past, we might move a little further toward safety in a world that seems to be teetering on the brink.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.