Decency Loses Its Moral Force

The Strzok hearing was shameful, but shame has fallen victim to partisan differences.

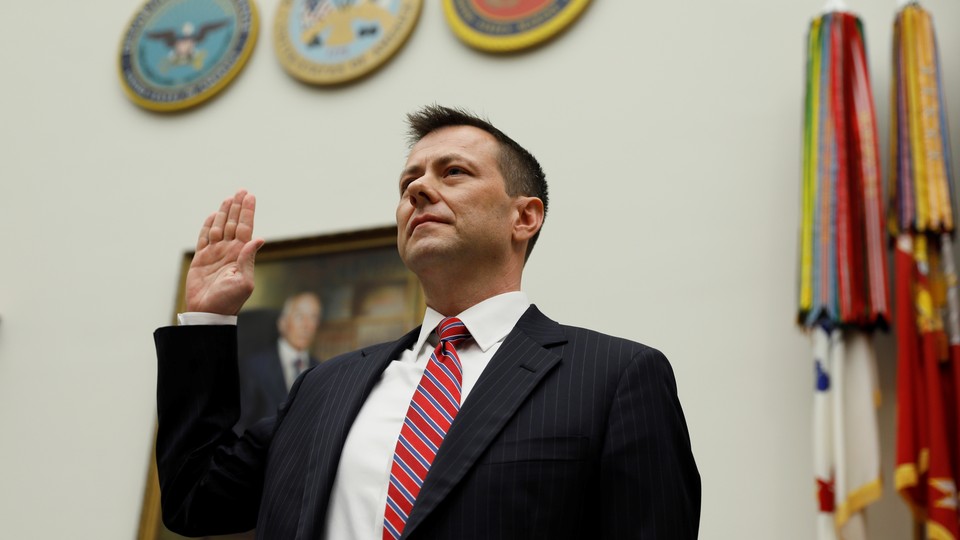

When Louie Gohmert, the Republican representative from Texas, jabbed a forefinger at FBI Agent Peter Strzok during last week’s House Judiciary Committee hearings and asked, “How many times did you look so innocent into your wife’s eyes and lie to her?” one of the Democrats in the room cried, “Have you no shame?” The echo of Joseph Welch’s question to Senator Joseph McCarthy at the 1954 Army–McCarthy hearing seemed all too just: Just as McCarthy had targeted the U.S. Army as a nest of subversives—he claimed to know of 130 Communists in its ranks—so Gohmert and his colleagues hoped to use Strzok to undermine the credibility of the FBI in the eyes of the American people.

But because shame does not operate today as it did 70 years ago, last week’s events could not possibly have had an outcome comparable to that of the Army hearings. McCarthy’s popularity plummeted after millions of Americans watched his testimony live. His reputation never recovered from the imputation of indecency. It’s unimaginable that Gohmert, or Trey Gowdy, or any of the chorus of defamers, will suffer a similar loss of standing today. The Army–McCarthy hearings were a climactic national drama carried live on the DuMont network, while the Judiciary Committee hearings were just another in a long line of similar proceedings. But it would scarcely have mattered if the whole country had tuned in. In the era of President Donald Trump, shame has lost its moral force.

Decency and the sense of shame that comes from violating standards of decency depend upon a tacit consensus on what it means to do right by others. Decency is not justice; since the tacit consensus of the 1950s did not include full civil rights for African Americans, or for that matter virtually anyone who was not a straight white male, very decent folk all over the country lived with perfect complacency in a caste society. Yet it is only when behavior formerly seen as unexceptionable begins to become a source of shame that broader social change becomes possible. That is as true of sexual abuse today as it was of racism half a century ago.

So yes, the social consensus of the 1950s depended on shrouding the most divisive issues in silence. Decency served as the nonpartisan virtue of that culture. Indeed, the supreme attribute of mid-century Hollywood films was the quiet, undemonstrative heroism of the decent man. Think of almost any film starring Henry Fonda. Twelve Angry Men doesn’t focus on Fonda’s politics any more than Mr. Smith Goes to Washington reveals Jimmy Stewart’s, but in the fortitude with which they stand up to prejudice, vitriol, ignorance, laziness, and impatience we recognize the mark of the decent man. No less do we recognize the substantive moral qualities of tolerance and fair-mindedness they embody.

McCarthy ultimately fell on the wrong side of the Fonda line. He had gathered strength throughout the early 1950s as he attacked institutions such as the State Department, which many Americans regarded as a nursery for the pampered elite. Swinging his wrecking ball at the Army, a revered institution that had protected the nation from the fascist threat, was a reckless move. (McCarthy had begun drinking heavily by this time.) Yet it was a purely personal attack that provoked Welch’s famous outburst. Challenged to produce his list of alleged subversives, McCarthy tried to change the subject by smearing Welch’s legal colleague, Fred Fisher, a private citizen with no connection to the hearings. That was a shameful act. Many people who shared McCarthy’s view of the communist menace still recoiled at his willingness to trample on the reputation of an ordinary American. Violent partisan difference could obscure, but not quite obliterate, the sense of how men and women should treat each other.

To register the difference between that world and our own, one should first note a striking role reversal. McCarthy was a rogue figure, if an immensely powerful one, sitting in the witness box. The congressional members of the Subcommittee on Investigations constituted the chorus of decency (though some, like Senator Karl Mundt, the chairman, had eagerly joined McCarthy’s red-baiting crusade). In last week’s drama, it was the witness who stood up for the traditional American value of straight shooting, not to mention the moral authority of law enforcement. It was the United States Congress that played the rogue.

There was something genuinely astonishing in the spectacle of Republican representatives trying to reduce the FBI to the status of a fifth column, as McCarthy had tried to do to the Army. Strzok had sent a text message to assure his colleague Lisa Page, with whom he was having an extramarital affair, that Trump would not win the election—“No. No he won’t. We’ll stop it.” Ted Poe, another Texan—another representative, that is, of the law and order capital of America—turned to Strzok and said, “You’re going to act on your bias. You’re going to ‘stop’ President Trump. How do we know that’s not rampant through the FBI?” Strzok rejoined, “A judge asks jurors, ‘Are you able to set aside your personal opinions and render a judgment based on the facts?’ and I and the men and women of the FBI every day take our personal beliefs and set them aside in vigorous pursuit of the truth wherever it lies.”

As a child of the ’60s, I feel extremely strange placing the FBI on the pedestal of decency. J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI blackmailed civil-rights leaders and threatened presidents; Richard Nixon used the FBI to investigate his enemies. Yet Peter Strzok stands for an FBI that, whatever its faults, serves the nation rather than a political master. G-men have become the Henry Fondas, the Jimmy Stewarts, of the present day—the true believers in an archaic code. In his congressional testimony last year, former FBI Director James Comey also provided a ritualized enactment of decency in the face of Republican attacks. I was foolish enough to write at the time that Comey’s testimony might serve to remind Americans of the value of neutral institutions and principles. No such luck: Comey’s plea for impartiality came to be seen on the right as proof of partiality (though he also didn’t help his case by embarking on a self-aggrandizing publicity tour).

Gohmert will pay no price for indecency. Yet it would be absurd to say that shame is dead. The parade of villains of the #MeToo movement illustrates the ongoing power of shame in contemporary culture. Harvey Weinstein and Charlie Rose suffered a reputational catastrophe equal to that of McCarthy. Of course Weinstein was such a hero of cultural progressives that he was able to spend decades mistreating women before he was finally brought down by relentless investigative journalism. What ultimately doomed these liberal icons was perhaps not their gross indecency, but their violation of the right of women in the workplace to be free of harassment, a core principle of contemporary liberal politics.

Perhaps the reason why Bill O’Reilly, or Fox News as an institution, paid a far more modest price for their transgressions—the former Fox News executive Bill Shine is now Donald Trump’s communications director—is that the mistreatment of women in the workplace does not occupy the same place in the corpus of conservative values. The alternative explanation is that the collective sense of what constitutes decent behavior outweighs ideological affinity on the left, but not on the right. Elected Democrats lined up to denounce President Bill Clinton’s private behavior during the Monica Lewinsky scandal, though none deemed it worthy of impeachment. Donald Trump’s vastly more outrageous behavior has provoked far less opprobrium from his own party. Republicans aren’t less decent than Democrats; rather, they have come to see political struggle in such apocalyptic terms that no merely personal form of shameful behavior can compete with the political stakes. Thus Christian conservatives hold their tongue rather than jeopardize their chances of getting a Supreme Court justice who will overturn Roe v. Wade. The party of personal morality thus becomes the party of indifference to personal morality.

In 2008, the Democrats nominated, and the country elected, a young, lanky, even-keeled fellow who imagined that he could restore the tarnished ideal of national decency. That didn’t turn out the way things do in the movies; eight years of Barack Obama persuaded the country to elect the most shameless man who has ever occupied the White House—possibly, in fact, the most shameless man in the United States of America. We’ll (probably) never know if Trump was right in saying that he could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot someone without losing much support. But his instincts are pretty good in these matters.

After Strzok finished reciting the true-blue virtues that he and his fellow FBI agents try to live by, Poe leaned into the microphone and said, “And I don’t believe you.” That’s where we are today.