The Dishonesty of the Abortion Debate

Why we need to face the best arguments from the other side

In 1956, two American physicians, J. A. Presley and W. E. Brown, colleagues at the University of Arkansas School of Medicine, decided that four recent admissions to their hospital were significant enough to warrant a published report. “Lysol-Induced Criminal Abortion” appeared in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology. It describes four women who were admitted to the hospital in extreme distress, all of them having had “criminal abortions” with what the doctors believed to be an unusual agent: Lysol. The powerful cleaner had been pumped into their wombs. Three of them survived, and one of them died.

The first woman arrived at the hospital in a “hysterical state.” She was 32 years old, her husband was with her, and she was in the midst of an obvious medical crisis: Her temperature was 104 degrees, and her urine was “port-wine” colored and contained extremely high levels of albumin, indicating that her kidneys were shutting down. Her husband eventually confessed that they had gone to a doctor for an abortion two days earlier. Four hours after admission, the woman became agitated; she was put in restraints and sedated. Two hours after that, she began to breathe in the deep and ragged manner of the dying. An autopsy revealed massive necrosis of her kidneys and liver.

The second woman was 28 years old and bleeding profusely from her vagina. “After considerable questioning,” she admitted that two days earlier, a substance had been injected into her womb by the same doctor who had treated the first patient. She was given a blood transfusion and antibiotics. Doctors performed a dilation and curettage, removing necrotic tissue that had a strong smell of phenol, then a main ingredient in Lysol. She survived.

The third woman was 35 and had been bleeding abnormally for two weeks. She told the physicians that her doctor had given her “a prescription for medicine,” but she denied having had an abortion. She was given a blood transfusion and antibiotics, but did not improve. Her pelvic discharge smelled strongly of phenol. She was given a D and C, and a placenta was removed. She recovered.

The fourth patient was 18 years old and had come to the hospital because of unusual bleeding, cramping, and “a loss of water through the vagina”—probably the beginning of labor, brought on by an abortion. Shortly after being admitted, she spontaneously aborted a four-and-a-half month fetus. Phenol was found in both the fetal and placental tissue. The girl recovered.

I have read many accounts of complications and deaths from the years when abortion was illegal in this country. The subject has always compelled me, because my mother told me many times that when she was a young nurse at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, she had twice sat beside girls as they died from botched abortions. Both girls were interviewed by detectives, who demanded to know the abortionists’ names, but both refused to reveal them. “They were too terrified,” my mother always said. The Arkansas cases contain strikingly consistent aspects of such reports: The women seem to have waited a long time before getting help, and they tried not to admit they’d had abortions, hoping they could be treated without telling the truth. Abortionists—to use the term of that era—typically extracted three promises from the women who sought them out: They must keep the procedure a secret; they must never reveal the abortionist’s name; and no matter what happened to them afterward, they must never contact him or her again.

What surprised me about the Arkansas doctors’ account was their confidence that while “the methods and drugs used in performing criminal abortions are legion,” Lysol was “one of the more rare abortifacients.” To the contrary, Lysol was commonly used in abortions. This was a fact that millions of women knew via the oldest whisper network in the country, but that physicians—almost all of them male—would discover slowly, leaving behind a bread-crumb trail of reports like this one: based on recent admissions, and available only to other doctors who happened to pick up a particular issue of a particular journal.

In addition to medical reports, we find evidence of Lysol abortions in personal accounts—the actor Margot Kidder, for example, spoke powerfully about hers—and in testimony from criminal proceedings. Court records from 1946, for instance, tell the story of a 16-year-old California girl named Rebecca, who moved in with her sister-in-law to hide her pregnancy and to get an abortion. A local woman named Sophie agreed to perform it. She made a mixture of boiling water, Lysol, and soap; injected the hot fluid into Rebecca’s uterus; and told her to walk around for two hours. In the middle of the night, the girl began having cramps that wouldn’t let up; she delivered a “well-formed, eight-inch fetus,” which her sister, Rayette, buried. Sophie returned the next day to collect the balance of her $25 fee. The girl was in distress but was given only aspirin. By that night, her symptoms had become intolerable, and Rayette brought her to the hospital. Sophie was later convicted and sent to prison; it’s unclear whether Rebecca survived.

By the 1960s, doctors seemed to have realized that Lysol was in fact a commonly used abortifacient, one with particular dangers. In 1961, Dr. Karl Finzer of Buffalo, New York, published a paper in the Canadian Medical Association Journal titled “Lower Nephron Nephrosis Due to Concentrated Lysol Vaginal Douches.” He described two cases. One of the women died; the other survived. In 1969, two physicians, Robert H. Bartlett and Clement Yahia, published a paper in The New England Journal of Medicine titled “Management of Septic Chemical Abortion With Renal Failure.” It included five case histories of women who had attempted abortions, two with Lysol. The doctors estimated that 200,000 to 1 million criminal abortions took place each year in America, and that in many parts of the country abortion was a leading cause of maternal death. Overall mortality for patients who had become septic from botched abortions and were admitted to a hospital was 11 to 22 percent, but for those whose abortions had been induced with soap or Lysol, the mortality rate was reportedly an astounding 50 to 66 percent. “These young women,” the authors reported dispassionately, “are all potentially salvageable.”

We will never know how many women had abortions via this method, or how many died because of it. Why was Lysol, with its strong, unpleasant smell and its corrosive effect on skin, so often used? Because its early formulation contained cresol, a phenol compound that induced abortion; because it was easily available, a household product that aroused no suspicion when women bought it; and because for more than three decades, Lysol advertised the product as an effective form of birth control, advising women to douche with it in diluted form after sex, thus powerfully linking the product to the notion of family planning.

In a seemingly endless series of advertisements published from the ’20s through the ’50s, the Lysol company told the same story over and over again: One woman or another had “neglected her feminine hygiene” and thereby rendered herself odious to her husband, leaving her “held in a web of indifference” and introducing “doubt” and “inhibitions” into their intimate life. It was illegal to advertise contraception nationally before 1977, so the Lysol ads performed a coy bit of misdirection—they said that if women didn’t douche after sex, they would lose their “dainty,” or “feminine,” or “youthful” appeal. The implication was that sex made them stink, which revolted their husbands. However, women in the past knew what women of the present know: Having sex doesn’t make a woman stink, and the only necessary items for keeping clean are soap and water.

Read with this in mind, the ads appear rife with coded references to the idea of contraception. One woman’s doctor has told her “never to run such careless risks” and prescribed Lysol. Another is told by her doctor that failing to douche with Lysol could “lead to serious consequences.” Many of the ads stress that Lysol works “even in the presence of mucous matter,” a possible reference to the by-products of intercourse; some promote the fact that it “leaves no greasy aftereffect,” probably a reference to the vaginal jellies that some women used as birth control.

A doctor tells one woman, “It’s foolish to risk your marriage happiness by being careless about feminine hygiene—even once!” This is the language of contraception: something that must be used every single time, that can lead to serious repercussions if skipped even once, that one should never be careless about. The “doubts” introduced to the marital lovemaking, and the “inhibitions,” are not the result of stink; they are the outcome of there being no reliable form of birth control and the constant anxiety that sex could result in an unwanted pregnancy.

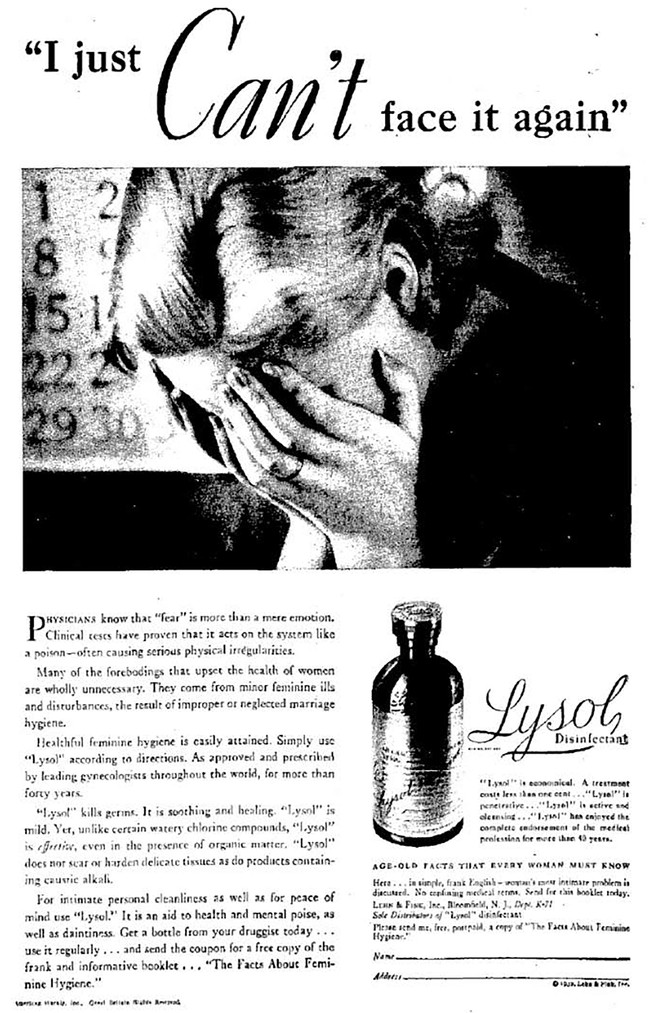

There are dozens of these ads on the internet, where they forever shock young feminists. I’ve seen so many of them that I thought I knew all of their tropes and euphemisms. But this summer I came across one that stopped me cold. It was a simple image of a very particular kind of female suffering. The woman in this ad was not caught in a web of indifference; she was not relieved because she had been prescribed Lysol by her doctor. The woman in this image has been “careless”; she is facing the “serious consequences.”

In a single panel, we see a line drawing of the kind of middle-class white housewife who was a staple of postwar advertising, although invariably the products she was selling were of use and of interest to women of all socioeconomic classes and all races—this product in particular. Her hair is brushed and shining, her nails are manicured, and she wears a wedding ring. But her head is buried in her hands, and behind her loom the pages of a giant calendar. Over her bowed head, in neat Palmer-method handwriting, is a single sentence: “I just can’t face it again.”

There’s a whole world in that sentence. To be a woman is to bear the entire consequence of sex. And here is one woman bearing that consequence: a married woman—probably with other children, for this is a matter of “again”—who for whatever reason is at her breaking point.

What could make a married woman living during the great postwar Baby Boom unable to face one more pregnancy? Start making a list of the possible reasons, and you might never stop. Maybe she’d had terrible pregnancies and traumatic births and she couldn’t go through another one. Maybe she had suffered terribly from postpartum depression, and she’d just gotten past it. Maybe her husband was an angry or violent man; maybe he had a tendency to blame her when she got pregnant. Maybe she had finally reached the point in her life when her youngest was in school and she had a few blessed hours to herself each day, when she could sit in the quiet of her house and have a cup of coffee and get her thoughts together. And maybe—just maybe—she was a woman who knew her own mind and her own life, and who knew very well when something was too much for her to bear.

The fictional woman with her head in her hands made me think of a real woman who died as a result of using Lysol to control her fertility: the 32-year-old woman in the Arkansas report whose husband took her to the hospital, where she soon died. Given the era and given that she was 32, there’s a fair chance that the couple had been married for at least a few years; there’s also a pretty good chance they already had children. For whatever reason, she just couldn’t face it again. She tried to do something to save herself—because when you can’t face something, there is no other choice. And she paid for it with her life.

Related Podcast

As a pro-life obstetric sonographer, Rebecca Shrader saw abortion as a black-and-white issue. But after she became pregnant, she found herself in the gray area. Listen on The Experiment.

Listen and subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google Podcasts

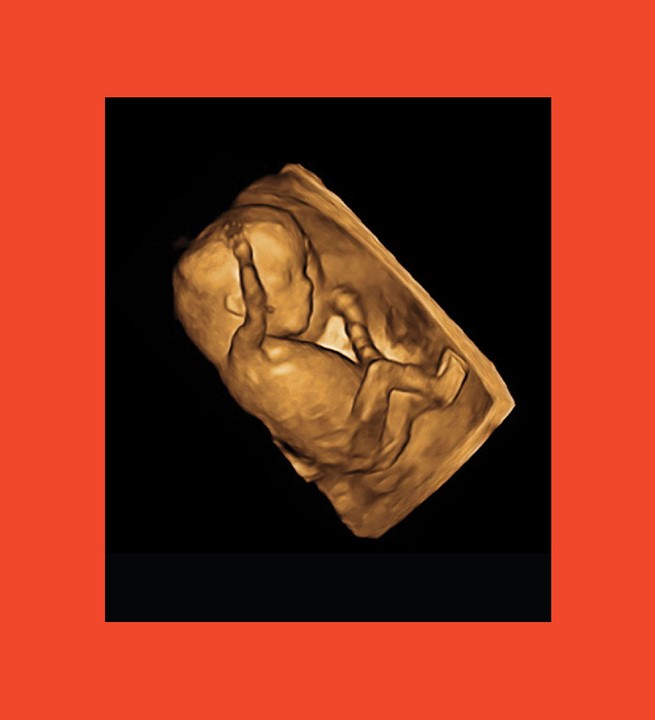

The first time I saw one of the new 3-D ultrasounds of a fetus in utero, I wasn’t entirely sure what I was looking at. It wasn’t anything like the black-and-white images I was used to seeing. It looked otherworldly, like we’d finally made contact with a planet we’ve always wanted to reach. In part it was the color, that glowing shade of amber that doesn’t suggest anything medical or technological. It calls to mind something almost ancient, something that suggests the beginning of all things. It reminded me, both in color and somehow in meaning, of the earliest photographs of the bog people of Northern Europe, a phenomenon that had absorbed my attention when I was very young. Those ancient and particular faces, those people you could easily have picked out of a crowd, buried deep in the peat for more than 2,000 years, keeping their secrets, slumbering. When farmers cutting turf began discovering them in the 1950s, they were so perfectly preserved that the men assumed they had uncovered the remains of very recent murder victims, not the bodies of people who had lived before the time of Christ. And that was the shocking thing about the bog people: They were so clearly like us, so obviously human and individual.

These sonograms are so richly detailed that many expectant mothers pay to have one made in a shopping-mall studio, much in the spirit in which they might bring the baby to a portrait studio. They are one thing and one thing only: baby pictures. Had they been available when I was pregnant, I would definitely have wanted one. When you’re pregnant, you are desperate to make contact. You know he’s real because of the changes in your own body; eventually you start to feel his. The first kicks are startling and exciting, but even once they progress so far that you can see an actual foot glancing across your belly and then disappearing again, he’s still a mystery, still engaged in his private work, floating in the aquatic chamber within you, more in touch with the forces that brought him here than with life as it is lived on the other side.

For a long time, these images made me anxious. They are proof that what grows within a pregnant woman’s body is a human being, living and unfolding according to a timetable that has existed as long as we have. Obviously, it would take a profound act of violence to remove him from his quiet world and destroy him.

“Most abortions happen in the first trimester,” a very smart and very kind friend reassured me. I didn’t need to worry about those detailed images of babies—by the time they had grown to such recognizably human proportions, most of them were well past the stage of development in which the majority of abortions take place. And I held on to that comforting piece of information, until it occurred to me to look at one of those images taken at the end of the first trimester. I often wish I hadn’t.

A picture of a 12-week fetus is a Rorschach test. Some people say that such an image doesn’t trouble them, that the fetus suggests the possibility of a developed baby but is far too removed from one to give them pause. I envy them. When I see that image, I have the opposite reaction. I think: Here is one of us; here is a baby. She has fingers and toes by now, eyelids and ears. She can hiccup—that tiny, chest-quaking motion that all parents know. Most fearfully, she is starting to get a distinct profile, her one and only face emerging. Each of these 12-week fetuses bears its own particular code: this one bound to be good at music; that one destined for a life of impatience, of tap, tap, tapping his pencil on the desk, waiting for recess.

What I can’t face about abortion is the reality of it: that these are human beings, the most vulnerable among us, and we have no care for them. How terrible to know that in the space of an hour, a baby could be alive—his heart beating, his kidneys creating the urine that becomes the amniotic fluid of his safe home—and then be dead, his heart stopped, his body soon to be discarded.

The argument for abortion, if made honestly, requires many words: It must evoke the recent past, the dire consequences to women of making a very simple medical procedure illegal. The argument against it doesn’t take even a single word. The argument against it is a picture.

This is not an argument anyone is going to win. The loudest advocates on both sides are terrible representatives for their cause. When women are urged to “shout your abortion,” and when abortion becomes the subject of stand-up comedy routines, the attitude toward abortion seems ghoulish. Who could possibly be proud that they see no humanity at all in the images that science has made so painfully clear? When anti-abortion advocates speak in the most graphic terms about women “sucking babies out of the womb,” they show themselves without mercy. They are not considering the extremely human, complex, and often heartbreaking reasons behind women’s private decisions. The truth is that the best argument on each side is a damn good one, and until you acknowledge that fact, you aren’t speaking or even thinking honestly about the issue. You certainly aren’t going to convince anybody. Only the truth has the power to move.

And here is one truth: No matter what the law says, women will continue to get abortions. How do I know? Because in the relatively recent past, women would allow strangers to brutalize them, to poke knitting needles and wire hangers into their wombs, to thread catheters through their cervices and fill them with Lysol, or scalding-hot water, or lye. Women have been willing to risk death to get an abortion. When we made abortion legal, we decided we weren’t going to let that happen anymore. We were not going to let one more woman arrive at a hospital with her organs rotting inside of her. We accepted that we might lose that growing baby, but we were not also going to lose that woman.

I thought about many women while I was writing this essay. The two girls my mother had watched die, all the women who endured Lysol abortions. But I also thought about a man: the husband of that 32-year-old woman who died in Arkansas, so long ago. It was an act of courage—a rare one—for him to bring her in himself, and to stay with her. Both of them had conspired in a criminal activity. How can we calculate that man’s misery? Imagine him sitting in the hospital waiting room, an obscene pantomime of the times he had likely sat in a very different kind of waiting room, as his children were being born. Imagine the disdain with which he would have been regarded by many of the nurses and doctors. It would have been impossible, during those wretched hours, to try to explain to them that his wife had said she just couldn’t face it again, and that he had tried to help her. At some point he would have been told that she was gone and also that there would have to be an autopsy. And then, when nothing else was left to do, no other form to sign and no other question to answer, imagine him getting in the car and making the terrible drive back to his house so that he could tell his children that their mother was never coming home again.

This article appears in the December 2019 print edition with the headline “The Things We Can’t Face.”