Wisconsin Is on the Brink of a Major Outbreak

The state’s coronavirus cases and hospitalizations are at an all-time high.

In New York, the decisive moment came in March. In Arizona and other Sun Belt states, it struck as the spring turned to summer. In every state that has so far seen a large spike of COVID-19 cases, there has been a moment when the early signs of an uptick are detectable—but a monstrous outbreak is not yet assured. Can a state realize what’s happening, and stop a surge in time? Wisconsin is about to find out.

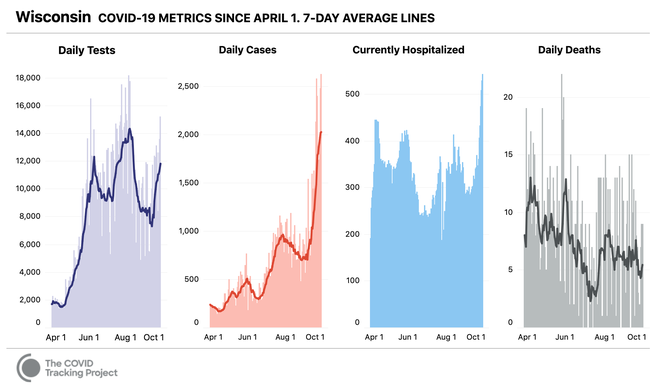

In the past week, Wisconsin has crashed through its own coronavirus records, reporting more cases and more COVID-19 hospitalizations than it has at any time since the pandemic began, according to the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic. It now ranks among the top states in new cases per capita, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and it is reporting more new cases, in absolute terms, than all states but California, Texas, and Florida.

Wisconsin’s outlook was deteriorating into the weekend. Yesterday, it reported more than 2,620 new cases of COVID-19, an all-time high. More than 540 people are hospitalized with the virus statewide.

The outbreak started about a month ago. It seemed, at first, like a product of students returning to college campuses. The University of Wisconsin at Madison brought back tens of thousands of students to campus in August. Within a week of classes starting, more than 1,000 of them tested positive, and the university shut down all in-person instruction. Other states in the Midwest saw similar spikes after colleges and universities restarted for the fall.

But those states are not seeing what Wisconsin is now. Cases are popping up in too many places, and among too many different age groups, to be blamed on college kids. In fact, every age group except 18-to-24-year-olds has seen cases rise this week, according to official data. “There’s a surge happening in cases across the state, for the most part,” Ajay Sethi, an epidemiology professor at the University of Wisconsin, told me.

Any coronavirus outbreak is bad news, but a surge in Wisconsin, at this moment, would be particularly awful. The problem is one of both political geography and poor timing. Wisconsin could determine the outcome of the presidential election: The state went for President Donald Trump in 2016 by only 22,748 votes, and both Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden have campaigned there this month. The election is little more than a month away, and if the threat of infection scares Wisconsinites away from polling places, the outbreak could play a role in who wins the state.

But this is also a bad time for any state to have an outbreak. As my colleague Alexis C. Madrigal and I wrote this month, the pandemic has become harder to track in the United States. Nationwide, the results of some new types of COVID-19 tests are not being consistently reported to local governments. In Wisconsin, testing has declined from its peak: The state reports fewer coronavirus tests a day now than it did in late July. This means that metrics that proved useful during the Sun Belt surge this summer, such as the percentage of tests that come back positive, have become less reliable. And this, in turn, has made it harder for officials and experts to forecast how large of an outbreak a state might be facing before the corresponding spikes in cases and hospitalizations.

In Wisconsin, neither of those numbers looks good. The Badger State is seeing an explosive rise in cases: On September 1, it reported an average of about 750 new coronavirus cases a day; now it reports more than 2,000 a day. Wisconsin has reported nearly as many new cases per capita this week as Texas and Georgia did at the peak of their outbreaks this summer, according to the CDC.

At the same time, the number of people hospitalized with COVID-19 in Wisconsin has more than doubled since the month began. “The surges are in Green Bay, in northeastern Wisconsin, and there’s a little evidence of an uptick in Milwaukee,” Sethi said. “A lot of these counties are where older individuals live, on average.”

But the state is not doomed to becoming the next Arizona, and it has already had some success halting the spread of the virus. After the University of Wisconsin at Madison shut down in-person classes earlier this month, case counts plummeted across the state. (The school is now loosening those restrictions.) Nationwide, many colleges and universities have successfully kept the virus in check through frequent testing and mask requirements.

But those tools aren’t as easy to deploy in a fractious state. This week, Governor Tony Evers, a Democrat, announced that the rising case counts forced him to extend a statewide mask mandate through November. Mask mandates are supported by public-health officials in the Trump administration and the White House Coronavirus Task Force. Yet the state’s top Republican legislators immediately attacked the move. “Moot, illegal, invalid, and almost assuredly headed for litigation,” Scott Fitzgerald, the state’s Senate majority leader, said in a statement. If the mask mandate is overturned in the state legislature, as Fitzgerald has repeatedly threatened, then Wisconsin’s odds of a deadly surge will worsen.

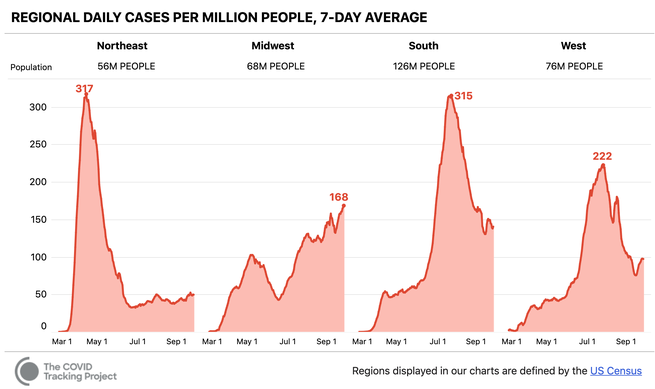

Leaders in Wisconsin should recognize that they hold the entire region’s fate in their hands, because their reckless action could set off a much larger blaze. The Midwest now reports more COVID-19 cases per capita than any other region. It is the only part of the country to have escaped a large-scale outbreak so far, but a major spike could prove especially devastating, because the residents of many midwestern states skew older.

The next few months will prove decisive in the Midwest. Infections didn’t really start going in the Southwest until the summer arrived, when the searing daytime heat drove people indoors, where the coronavirus seems to spread most easily. In the Midwest, indoor season arrives in late autumn. It is nearly 80 degrees Fahrenheit in Green Bay today. The weather in December probably won’t be as favorable.